the throwing of rocks?”

“You misunderstand me, sir,” said Leo Matienne. “I meant only to say that the elephant did not ask to come crashing through the roof of the opera house. Would any sensible elephant wish for such a thing? And if she did not wish for it, then how can she be guilty of it?”

“I ask you for possible solutions,” said the chief of police. He put his hands on top of his head.

“Yes,” said Leo Matienne.

“I ask what action should be taken,” said the chief. He pulled at his hair with both hands.

“Yes,” said Leo Matienne again.

“And you talk to me about sensible elephants and what they wish for?” shouted the captain.

“I think it is pertinent, sir,” said Leo Matienne.

“He thinks it is pertinent,” said the chief.

“He thinks it is pertinent.” He pulled at his hair again. His face became very red.

“Sir,” said another policeman, “what if we found the elephant a home, sir?”

“Yes,” said the chief of police. He turned around and faced the policeman who had just spoken. “Why did I not think of it? Let us dispatch the elephant immediately to the Home for Wayward Elephants Who Engage in Objectionable Pursuits Against Their Will. It is right down the street, is it not?”

“Is it?” said the policeman. “Truly? I had not known. There are so many worthy charitable institutions in this enlightened age; why, it’s become nearly impossible to keep track of them all.”

The chief pulled very hard at his hair.

“Leave me,” he said softly. “All of you. I will solve this without your help.”

One by one, the policemen left the police station.

The small policeman was the last to go. He lifted his hat to the chief.

“I wish you a good evening, sir,” he said, “and I beg that you consider the idea that the elephant is guilty of nothing except being an elephant.”

“Leave me,” said the chief of police, “please.”

“Good evening, sir,” said Leo Matienne again. “Good evening.”

The small policeman walked home in the gloom of early evening. As he walked, he whistled a sad song and considered the fate of the elephant.

To his mind, the chief was asking the wrong questions.

The questions that mattered, the questions that needed to be asked, were these: where did the elephant come from? And what did it mean that she had come to the city of Baltese?

What if she was just the first in a series of elephants? What if, one by one, all the mammals and reptiles of Africa were to be summoned to the stages of opera houses all across Europe?

What if, next, crocodiles and giraffes and rhinoceroses came crashing through roofs?

Leo Matienne had the soul of a poet, and because of this, he liked very much to consider questions that had no answers.

He liked to ask “What if?” and “Why not?” and “Could it possibly be?”

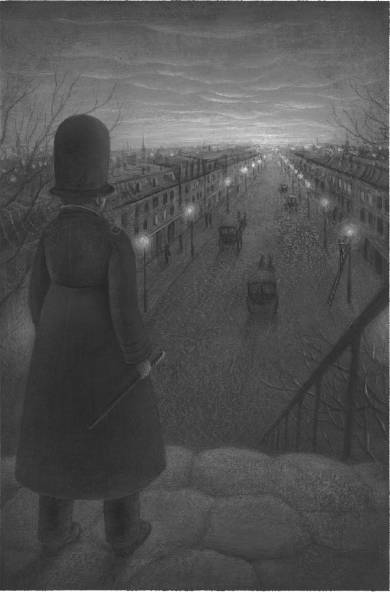

Leo came to the top of the hill and paused. Below him the lamplighter was lighting the lamps that lined the wide avenue. Leo Matienne stood and watched as, one by one, the globes sprang to life.

What if the elephant had come bearing a message of great importance?

What if everything was to be irrevocably, undeniably changed by the elephant’s arrival?

Leo stood at the top of the hill and waited for a long while, until the avenue below him was well and fully lit, and then he continued walking down the hill and onto the lighted path, towards his home.

He whistled as he walked.

What if?

Why not?

Could it be?

Peter stood at the window of the attic room of the Apartments Polonaise. He heard Leo Matienne before he saw him; always, because of the whistling, Peter heard Leo before he saw him.

He waited until the policeman appeared, and then he threw open the window and stuck his head out. He shouted, “Leo Matienne, is it true that there is an elephant and that she came through the roof and that she is now with the police?”

Leo stopped. He looked up.

“Peter,” he said. He smiled. “Peter Augustus Duchene, fellow resident of the Apartments Polonaise, little cuckoo bird of the attic world. There is indeed an elephant. It is true. And it is true, also, that she is in the custody of the police. The elephant is imprisoned.”

“Where?” said Peter.

“I cannot say,” said Leo Matienne. “I cannot say, because I am afraid that I do not know. They are keeping it the strictest possible secret, you see, what with elephants being such dangerous and provoking criminals.”

“Close the window,” called Vilna Lutz from his bed. “It is winter, and it is cold.”

It was winter, true.

And true, also, it was quite cold.

But even in the summertime, Vilna Lutz, when he was in the grip of his strange fever, would complain of the cold and demand that the window be shut.

“Thank you,” said Peter to Leo Matienne. He closed the window and turned and faced the old man.

“What were you speaking of?” said Vilna Lutz. “What manner of nonsense were you shouting from windows?”

“An elephant, sir,” said Peter. “It is true. Leo Matienne says that it is true. An elephant has arrived. An elephant is here.”

“Elephants,” said Vilna Lutz. “Pooh. Imaginary beasts, denizens of bestiaries, demons from who knows where.” He fell back against the pillow, exhausted by his diatribe, and then jerked suddenly upright again. “Hark! Do I hear the crack of muskets, the boom of cannon?”

“No, sir,” said Peter. “You do not.”

“Demons, elephants, imaginary beasts.”

“Not imaginary,” said Peter. “Real. This elephant is real. Leo Matienne is an officer of the law, and he says that it is so.”

“Pooh,” said Vilna Lutz. “I say ‘pooh’ to that mustachioed officer of the law and his imagined creature.” He lay back against the pillow. He turned his head first to one side and then to the other. “I hear it,” he said. “I hear the sounds of battle. The fight has begun.”

“So,” said Peter softly to himself, “it must be true, mustn’t it? There is an elephant now, so the fortuneteller was right, and my sister lives.”

“Your sister?” said Vilna Lutz. “Your sister is dead. How often must I tell you? She never drew breath. She did not breathe. They are all dead. Look out over the field and you will see: they are all dead, your father among them. Look, look! Your father lies dead.”

“I see,” said Peter.

“Where is my foot?” said Vilna Lutz. He cast a wild look around the room. “Where is it?”

“On the bedside table.”

“On the bedside table,

“On the bedside table, sir,” said Peter.

“There,” said the old soldier. He picked up the foot. “There, there, old friend.” He gave the wooden foot a loving pat and then let his head sink back on the pillow. He pulled the blankets up under his chin. “Soon,” he said, “soon, I will put on the foot, Private Duchene, and we will practise manoeuvres, you and I. We will make a great soldier out of you yet. You will become a man like your father. You will become, like him, a soldier brave and true.”