Peter turned away from Vilna Lutz and looked out of the window at the darkening world. Downstairs, far below, a door slammed. And then another. He heard the muffled sound of laughter and knew that Leo Matienne was being welcomed home by his wife.

What was it like, Peter wondered, to have someone who knew you would always return and who welcomed you with open arms?

He remembered being in a garden at dusk. The sky was purple and the lamps had been lit, and Peter was small. His father picked him up and tossed him high and then caught him, over and over again. Peter’s mother was there too; she was wearing a white dress that glowed bright in the purple dusk, and her stomach was large like a balloon.

“Don’t drop him,” said Peter’s mother to his father. “Don’t you dare drop him.” She was laughing.

“I will not,” said his father. “I could not. For he is Peter Augustus Duchene, and he will always return to me.”

Again and again, Peter’s father threw him up in the air. Again and again, Peter felt himself suspended in nothingness for a moment, just a moment, and then he was pulled back, returned to the sweetness of the earth and the warmth of his father’s waiting arms.

“See?” said his father to his mother. “Do you see how he always comes back to me?”

It was fully dark now in the attic room of the Apartments Polonaise. The old soldier tossed from side to side in the bed. “Close the window,” he said. “It is winter, and it is cold.”

The garden that held Peter’s father and mother seemed far away, so far that he could almost believe that the memory, the garden, had existed in another world entirely.

But if the fortuneteller was to be believed (and she must be believed; she must, he thought), the elephant knew the way to that garden. She could lead him there.

“Please,” said Vilna Lutz, “the window must be closed. It is so cold; it is so very, very cold.”

Chapter Four

That winter, the winter of the elephant, was, for the city of Baltese, a particularly miserable season. The skies were filled with thick, lowering clouds that obscured the sun and condemned the city to a series of days that resembled nothing so much as a single, unending dusk.

It was unimaginably, unbelievably cold.

Darkness prevailed.

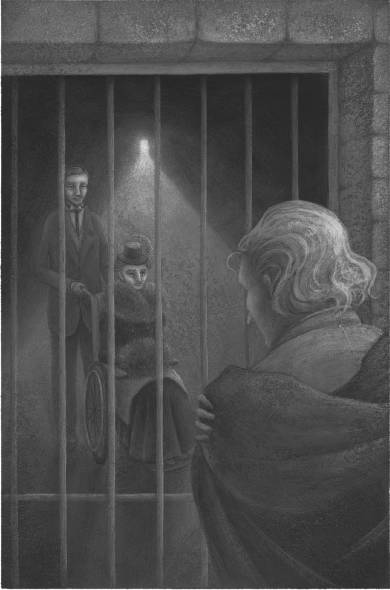

The crippled Madam LaVaughn, sunk deep in a gloom of her own, took to visiting the prison.

She came in the late afternoon.

The magician could hear the accusing creak of the wheels of her chair as it was pushed down the long corridor. Yet, when the noblewoman appeared before him, her eyes wide and pleading, a blanket thrown over her useless legs and her manservant standing to attention behind her, the magician managed, somehow, each time, to be astonished at her presence.

Madam LaVaughn spoke to the magician. She said, “But perhaps you do not understand. I was crippled, crippled by an elephant that came through the roof!”

The magician responded. He said, “Madam LaVaughn, I assure you, I intended only lilies. I intended only a bouquet of lilies.”

Every day, the magician and the noblewoman spoke to each other with an urgency that belied the fact that they had spoken the same words the day before and the day before that.

Every afternoon, the magician and Madam LaVaughn faced each other in the gloom of the prison and said exactly the same thing.

The noblewoman’s manservant was named Hans Ickman, and he had been in the service of Madam LaVaughn since she was a child. He was her adviser and confidant, and she trusted him in all things.

Before he came to serve Madam LaVaughn, however, Hans Ickman had lived in a small town in the mountains, and he had had there a family: brothers, a mother and a father, and a dog who was famous for being able to leap across the river that ran through the woods beyond the town.

The river was too wide for Hans Ickman and his brothers to leap across. It was too wide even for a grown man to leap. But the dog would take a running jump and sail effortlessly across the water. She was a white dog and small, and other than her ability to jump the river, she was in no way extraordinary.

Hans Ickman, as he aged, had forgotten about the dog entirely; her miraculous ability had receded to the back of his mind. But the night that the elephant had come crashing through the ceiling of the opera house, the manservant had remembered again, for the first time in a long while, the little white dog.

Standing in the prison, listening to the endless and unvarying exchange between Madam LaVaughn and the magician, Hans Ickman thought about being a boy, waiting on the bank of the river with his brothers, and watching the dog run and then fling herself into the air. He remembered how, in mid-leap, she would always twist her body, a small unnecessary gesture, a fillip of joy, to show that this impossible thing was easy for her.

Madam LaVaughn said, “But perhaps you do not understand.”

The magician said, “I intended only lilies.”

Hans Ickman closed his eyes and remembered the dog suspended in the air above the river, her white body set afire by the light of the sun.

But what was the dog’s name? He could not recall. She was gone and her name was gone with her. Life was so short; so many beautiful things slipped away. Where, for instance, were his brothers now? He did not know; he could not say.

Madam LaVaughn said, “I was crushed, crushed by an elephant!”

The magician said, “I intended only—”

“Please,” said Hans Ickman. He opened his eyes. “It is important that you say what you mean to say. Time is too short. You must speak words that matter.”

The magician and the noblewoman were silent for a moment.

And then Madam LaVaughn opened her mouth. She said, “But perhaps you do not understand.”

The magician said, “I intended only lilies.” “Enough,” said Hans Ickman. He took hold of Madam LaVaughn’s chair and turned it around. “That is enough. I cannot bear to hear it any more. I truly cannot.”

He wheeled her away, down the long corridor and out of the prison and into the cold, dark Baltesian afternoon.

“But perhaps you do not understand. I was crippled—”

“No,” said Hans Ickman, “no.”

Madam LaVaughn fell silent.

And it was in this manner that she paid her last official visit to the magician in prison.

Peter could, from the window of the attic room in the Apartments Polonaise, see the turrets of the prison. He could see, too, the spire of the city’s largest cathedral and the gargoyles crouched there, glowering, on its ledges. If he looked out into the distance, he could see the great, grand homes of the nobility high atop the hill. Below him were the twisting, turning cobblestoned streets, the small shops with their crooked tiled roofs, and the pigeons who forever perched atop them, singing sad songs that did not quite begin and never truly ended.

It was a terrible thing to gaze upon it all and know that somewhere, beneath one of those roofs, hidden, perhaps, in some dark alley, was the very thing that he needed, wanted, and could not have.

How could it be that against all odds, all expectations, all reason, an elephant could miraculously appear in the city of Baltese and then just as quickly disappear; and that he, Peter Augustus Duchene, who needed desperately to find her, did not know – could not even begin to imagine – the how or where of searching for her?

Looking out over the city, Peter decided that it was a terrible and complicated thing to hope, and that it