The resistance experienced so many disappointments and anxieties, it saw so many valiant efforts turn to dust, that few of its members could help but be overcome by feelings of despair. Jens Peter Jessen, for instance, fell increasingly prey to such emotions and at times withdrew from society altogether. Tresckow, Olbricht, Hassell, and Johannes Popitz, by contrast, were less affected, while the irrepressible Goerdeler even began dreaming of what he called a “partial action,” by which he meant the assassination of a more accessible Nazi of secondary rank or some other spectacular deed that, if accomplished at just the right moment, would bring “the whole house of cards crashing down.” He was persuaded not to press ahead with his plans at a dinner in the home of former state secretary Erwin Planck, where the attorney Carl Langbehn, Hassell, General Thomas, and others argued that “Hitler’s prestige is still solid enough that if he’s left standing he’ll be able to launch a counterattack that will end in at least chaos or civil war.”16

At the fronts, the tides of war had now begun to turn. In early July Hitler attempted to regain the upper hand in the East through Operation Citadel, a massive panzer offensive against a Russian salient near Kursk; it ended in failure. A few days later the Allies landed in Sicily, creating a second front, and on July 25 Mussolini was over thrown. Tresckow, just released from his position on the staff of Army Group Center, canceled a vacation he had planned to take for health reasons and went to Berlin. Shortly after arriving he told Rudiger von der Goltz, a cousin of Christine von Dohnanyi, that the war was lost and that “everything therefore must be done to end it soon.” That meant “the leadership would have to go.”17

At about the same time, Tresckow finally succeeded in convincing Colonel Helmuth Stieff, the only conspirator who had access to Hitler in the regular course of his duties, to keep his pledge to participate in an assassination attempt. This was a promising turn of events. Warned by Schlabrendorff that Kluge seemed to be backsliding in his absence, Tresckow then managed to persuade the field marshal to come to Berlin, where Tresckow sought to keep him in the conspiracy. He also arranged for Kluge to meet with Olbricht and Goerdeler, as well as with Beck, who had recently been released from the hospital. At the end of a long conversation about foreign affairs and the policy of the government to be formed after the coup, Kluge stated with surprising firmness that since Hitler would not make the necessary decisions to end the war and was unacceptable to the Allies as a negotiating partner he had to be overthrown by force. But now it was Goerdeler who voiced his adamant opposition, once again swept away by his optimism and his belief in the power of reason. He reminded the conspirators of the duty of the army commanders and the chief of general staff “to speak frankly with the Fuhrer.” After that, he said, everything else would fall into place: “Anybody can be won over to a good cause.” Kluge and Beck could no longer be dissuaded, however, and shortly thereafter Goerdeler, suddenly fired with new enthusi asm, informed the Swedish banker Jakob Wallenberg that a putsch was planned for September. Schlabrendorff would then be sent to Stockholm to initiate peace negotiations.18

This announcement, like so many before it, was not to be fulfilled. First of all, Goerdeler probably cited far too early a date. The coup was apparently planned for the second half of October at the earliest. Then on October 12 Kluge was badly injured in an automobile accident and was laid up for a considerable period, which meant that no assassination attempts would be staged in the foreseeable future by the armies at the fronts. After so many failed attempts, Olbricht now turned with renewed vigor to an idea that had already been considered: using the home army for both the assassination and the coup.

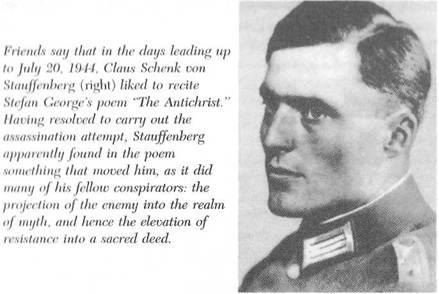

What was lacking above all was an assassin. Around August 10, however, Tresckow had been introduced at Olbricht’s house to a young lieutenant colonel who would be taking up the duties of chief of staff of the General Army Office on October 1. He had been badly wounded in a strafing attack while serving on the North African front in April. He had lost his right hand as well as the third and fourth fingers of his left, and he wore a black patch over his left eye. After a lengthy stay in the hospital, he had asked the surgeon, Ferdinand Sauerbruch, how much longer he would need to recuperate. On hearing that two more operations and many months of convalescence would be necessary, he shook his head, saying he didn’t have that much time-important things needed to be done. While still in the hospital he explained to his uncle and close confidant Nikolaus von Uxkull, “Since the generals have failed to do anything, it’s now up to the colonels.”19 His name was Count Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg. Stauffenberg imbued the resistance with a vitality that had long been lacking but that now served to encourage Olbricht’s cautious deliberations and heighten Tresckow’s determination. He seemed to send an electric charge through the lifeless resistance networks as he quickly and naturally assumed a leadership role. This effect stemmed not only from the infectious energy that so many of his contemporaries have described but also from his unusual combination of exuberant idealism and cool pragmatism. He was familiar with all the complex religious, historical, and traditional reasons that had repeatedly stood in the way of action, but he had not lost sight of the far more basic truth that there are limits to loyalty and obedience. He was therefore able to put aside scruples about treason and the breaking of solemn oaths. Possessed of a finely honed sense of what was appropriate under the circumstances, he dismissed the foreign policy concerns of almost all the other members of the resistance, simply assuming that a German government that had overthrown the Nazis would be able to negotiate a peace treaty despite the Casablanca declaration. Most important, he was determined to act at all costs. Like Tresckow, he rejected the tendency of the resistance to make its actions contingent on circumstance-a failing that had first become apparent in 1938 and had resurfaced that spring in the collapse of the Oster group.

Stauffenberg was a scion of the Swabian nobility, related to the distinguished Gneisenau and Yorck families. When he was seventeen he and his brothers had joined the circle of intellectuals and students led by the famous poet Stefan George. Although he stood vigil at George’s deathbed in December 1933, along with some friends, he was not a true disciple. Like many other young officers, he had welcomed Hitler’s nomination as chancellor in 1933 and had agreed, in theory at least, with some of the Nazi platform, especially unification with Austria and hostility to the Treaty of Versailles. By the time of the Blomberg and Fritsch affairs, however, he had already begun to have serious doubts about the Nazis, doubts that Hitler’s recklessness during the Sudeten crisis only hardened, “That fool is headed for war,” he said. But when war was finally declared he threw himself into his chosen profession like a devoted soldier. His response to the numerous atrocities was that once the war was over there would be plenty of time to get rid of the “brown plague”—a reaction he shared with many of his colleagues.20

Stauffenberg proved to be a brilliant staff officer and was promoted to the army high command in June 1940. Since the launching of the Soviet campaign he had become familiar with the army’s organizational inefficiency and the complicated tangle of competing military hierarchies. Moved by his sense of “outrage that Hitler… was too stupid… to do what was required,” he strove stubbornly, though ultimately in vain, to form units composed of Russian volunteers so as to undermine the Nazis’ senseless policies toward the “peoples of the East.” At first his critical view of the regime was spurred by technical, military, and national concerns. Gradually, though, moral issues came more and more to the fore, and in the end all these considerations played their part in a decision best summarized by his laconic answer to a question asked of him in 1942 about how to change Hitler’s style of leadership: “Kill him.”21

The historian Gerhard Ritter has written that Stauffenberg had “a streak of demonic will to power and a belief that he was born to take charge” without which “the resistance was in danger of becoming bogged down in nothing but plans and preparations.”22 Once, when a member of the high command, appalled by the needless sacrifice of German soldiers and the staggering brutality being inflicted on the Soviet civilian population, asked Stauffenberg if it was possible to impress upon Hitler the truth of the situation, the young officer shot back, “The point is no longer to tell him the truth but to get rid of him,” a remark that sharply repudiated Goerdeler’s incurable optimism.23 At headquarters in Vinnitsa in October 1942 Stauffenberg spoke out openly before a gathering of officers about the “disastrous course of German policy in the East,” saying that everyone had remained silent even though it sowed hatred on all sides. Many witnesses have also reported his criticisms of generals who considered honor, duty, and service to be not binding ideals but simply grounds for making excuses; one report speaks of his contempt for all the “carpet layers with the rank of general. 2I

Stauffenberg’s entry into resistance circles caused an enormous shift in the distribution of power and influence without his doing anything in particular. It was inevitable that he would spark conflicts as well as hopes. Goerdeler and his close associates were particularly vexed by the eclipse of the civilian groups, which they felt should dominate the resistance, and began to mutter derisively about Stauffenberg’s lofty political ambitions and vaguely socialist tendencies. Soviet and East German historians later turned this grumbling to their advantage by depicting Stauffenberg as having moved close to Moscow in his political sympathies. But this myth, its somewhat