grotesque origins, and the intentional exaggerations it underwent have all been investigated and disproved.25

What is clear is that Colonel Stauffenberg was far from the flunky whom the sell-confident Goerdeler had always expected and previously always found in his collaborators from the military. In Stauffenberg a far more politically minded officer stepped forward, one who had no intention of simply putting himself at the beck and call of some group and its “shadow chancellor.” What distinguished Stauffenberg from Goerdeler was less the former mayor’s conservative, bourgeois values than his reluctance to employ violence and his rationalist delusion that Hitler could be made to see the error of his ways. Stauffenberg considered this as far-fetched as the highly con templative opposition shared by many in the Kreisau Circle, which he derided as a “conspirator’s tea party.” As the man who would soon lead the actual coup attempt, he almost inevitably found himself at odds with both groups of conspirators, although for different reasons. On the whole, he felt closest to Julius Leber, the undogmatic Social Democrat with whom he shared the realistic political views and normative pragmatism of a man of action.

In early September 1943 Stauffenberg and Tresckow set about revising Olbricht’s plans for a coup once again, with an eye to correcting the inadequacies that had become apparent during the March attempt. Ironically, the original plans were based on a strategy that had been designed by Olbricht’s staff and approved by Hitler for dealing with “internal disturbances”—that is, an uprising by the millions of so-called foreign workers in Germany, possibly at the instigation or with the help of the Communist underground or enemy paratroopers. Under the code name Operation Valkyrie, the diffuse, scattered elements of the “reserve army”—trainees, soldiers on leave, and training staff and cadres-would immediately be united and transformed into fighting units. After the experiences of March Olbricht developed a second stage of this plan and had it approved in late July 1943. Henceforth “Valkyrie I” designated a strategy to ensure the combat readiness of all units and “Valkyrie II” provided for their “swiftest possible assemblage” into “battle groups ready for action.”

Tresckow and Stauffenberg hit upon what many have called the “brilliant” idea of further tailoring these official plans, which Olbricht apparently considered adequate, to the specific needs of a coup by adding a secret declaration, to be issued immediately upon Hitler’s assassination. It would begin: “The Fuhrer Adolf Hitler is dead! A treacherous group of party leaders has attempted to exploit the situation by attacking our embattled soldiers from the rear in order to seize power for themselves!” The Reich government, the announcement continued, had “declared martial law in order to maintain law and order.” Simultaneously, government ministries and Nazi Party offices would be occupied, as would radio stations, telephone offices, and the concentration camps. SS units would be disarmed, and their leaders shot if they resisted or refused to obey.

Thus the conspirators succeeded in standing Operation Valkyrie, and the plan for dealing with “internal disturbances,” on its head. Stauffenberg and Tresckow’s additional declaration would pin the blame for the uprising that they themselves were staging on the Nazi Party, a strategem intended to pacify those who would probably oppose the coup if they knew the true situation. The entire plan to overthrow the regime, therefore, depended on an enormous hoax carried out in large part by scores of officers and troops obliviously following orders.

Since the success of the undertaking relied considerably on the element of surprise which, in turn, would set in motion blind adherence to the automatic chain of command-secrecy was of the essence. All written information was handled by Tresckow’s wife, Erika, and by Margarete von Oven, who had been Hammerstein’s secretary during his days as chief of army command. Both women wore gloves when they worked so as not to leave fingerprints. All meetings were held out of doors at various locations in the Grunewald, but they often had to be canceled and then, with great difficulty, rescheduled because of Allied air raids, breakdowns in public transportation, or other unforeseeable events. One evening a group of conspirators were returning from one of their meetings in the Grunewald when an SS van came screeching to a halt directly beside them on Trabenerstrasse. Margarete von Oven was carrying all the documents about the uprising under her arm, and “when the SS men poured out, each of them thought the conspiracy had been discovered and they would be arrested at once. But the SS men paid no attention to the three passersby and disappeared into a house.”26

Despite the conspirators’ efforts, the Valkyrie plan had a serious and possibly fatal flaw: neither Olbricht nor Stauffenberg was authorized to order its implementation. Hitler had expressly reserved this authority for himself, with the commander of the reserve army, General Friedrich Fromm, authorized to give the cue only in an emer gency. Therefore Olbricht or Stauffenberg had either to win Fromm over or else to usurp his position and set Valkyrie in motion in his name. Olbricht was prepared to take Fromm into custody if necessary and sign the orders himself, but that risked questions about the chain of command and delays that might imperil the entire enterprise. It has also been pointed out rightly that this was a tactic that could work only once. If the conspirators failed to usurp Fromm’s position “the first time around, there would be no second chance.”27

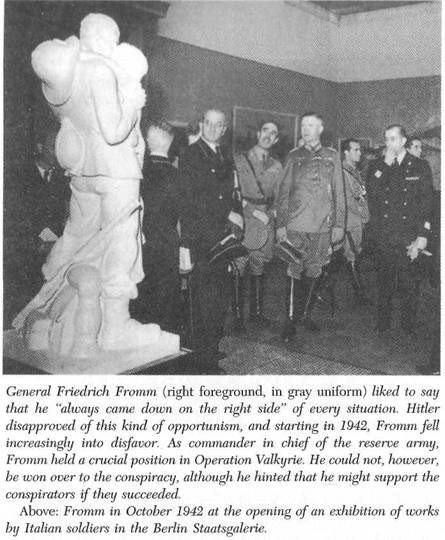

General Fromm was a large, shrewd man who liked to boast that he “always came down on the right side.” When Halder asked him earnestly in the fall of 1939 to support the generals’ coup that was being plotted, Fromm evaded the issue at first and then requested lime to consider the matter. He was torn by doubts about the chances of success and tormented by the fact that he had compromised himself by responding to Halder at all. Finally he formally absolved himself of involvement by recording the affair in his official diary.

Fromm certainly did not number among “Hitler’s generals,” and to his friends he frequently expressed his distaste for the Nazis. He was also clever enough to deduce what Olbricht and Stauffenberg were up to from all the secretive activity in their offices and the visitors whom they received, he always acted, however, as if it was none of his business. He slipped up only once, in mid-July 1944, when, in a particularly buoyant mood, he told Olbricht to be sure, in the event of a putsch, not to forget Wilhelm Keitel, whom Fromm hated.28 Although Fromm did nothing to hinder the uprising, no one who knew him had any doubt that he would not assist it either and, most important, that he would definitely not sign the Valkyrie orders. The question of how he should be handled therefore remained open. By the end of October all other preparations were ready. Tresckow gave Witzleben the orders declaring martial law, and Witzleben, who was to assume command of the Wehrmacht once a coup was under way, affixed his signature.

Scarcely had these preparations been completed, however, when Tresckow was ordered back to the front. Thus it was Stauffenberg who look on responsibility for igniting the “initial spark.” It was hoped that Tresckow would again assume a pivotal position in the military command from which he could provide support from the front as soon as the home army initiated the uprising, but this was not to be. The army personnel office had recommended him, along with other candidates, to serve as chief of staff for Army Group South under Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, but Manstein rejected him. Instead, Tresckow assumed command of an infantry regiment in a division led by Manstein. Rumor had it that he was being put in “cold storage.”29

The problem now as ever was to find an officer who had access to Hitler and was determined to kill him. Stieff had recently declared himself ready, but when Stauffenberg sought him out he stalled. He did, however, take possession of the explosives Stauffenberg brought him and finally demanded the assistance of an accomplice, apparently in order to help steel himself. Stauffenberg turned to Colonel Joachim Meichssner, the head of the organizational section of the OKW operations staff, who had tentatively promised in September to be the assassin. At the same time, Stieff was apparently considering making an attempt with two young officers on his staff, Major Joachim Kuhn and First Lieutenant Albrecht von Hagen; but after further consideration, he again backed out, explaining that it was impossible to carry explosives into a briefing without being noticed. In truth, it was probably fear that deterred this lively and somewhat unstable man from action.

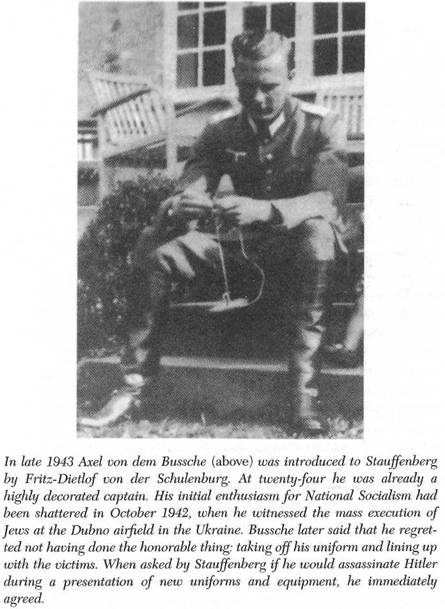

These harrowing efforts to find someone who would set off the “initial spark” prompted Stauffenberg to make contact, through Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, with one of the “reliable young officers” he had heard about in the spring. Axel von dem Bussche was a highly decorated twenty-four-year-old captain. His initial naive enthusiasm for Hitler and National Socialism had already dimmed considerably when, in early October 1942, he happened to witness the mass execution of several thousand Jews at the Dubno airfield in the Ukraine, a shock he never recovered from. There were, he said, only three possible ways for an honorable officer to react: “to die in battle, to desert, or to rebel.” When Stauffenberg now asked him if he would be willing to kill Hitler, Bussche accepted without hesitation.

The plan was to use a previously scheduled presentation of new uniforms and equipment to lure Hitler from