ated the other factions. As a result not even the loosest of ties were forged, especially as Moscow itself was apparently not interested in developing this group into a cell or even a center of political resistance. Rather, the inner circle of the Red Orchestra was used as an intelligence-gathering service for the Soviet Union.

Thus the question of establishing contacts with the Soviet Union arose at this point only as a tactical ploy to elicit more interest from the Western powers. But the resistance soon dropped this plan too. One of the strongest pieces of evidence against Stauffenberg’s alleged Communist sympathies is that he turned down the appeals of the National Committee for a Free Germany with the comment, “I am betraying my government; they are betraying their country.”44 Stauffenberg not only supported the attempts of men like Goerdeler, Trott, and Gisevius to reach some kind of understanding with the Western powers but later joined in those efforts himself. Although the Gestapo was eager after July 20 to find some evidence of collusion between the conspirators and the Soviet Union or one of its agents, they failed to find any.

There was yet another aspect to this question-namely, the resistance’s connections with the Communist underground. Only isolated remnants had survived the shocking announcement of the Hitler-Stalin pact, so that it was difficult to determine their strength. The uncertainty prompted Leber to respond positively to various Communist overtures. Although there was still no question of including the Communists in the conspiracy, there was talk of an “opening to the left,” and of determining how the Communist leadership would react to a coup.

After much argument, a discussion of the issue was finally held in Yorck’s house on June 21. There were violent differences of opinion. Leuschner opposed any sort of rapprochement, insisting that the Communist apparatus had been infiltrated by the Gestapo. The Kreisauers Theodor Haubach and Paulus van Husen were also dead set against establishing any contacts. Only Adolf Reichwein advocated “a kind of socialist solidarity,” the outgrowth of his “almost embittered socialism.” The reticence of many of the participants was greatly reduced, however, when Leber reported that he had been contacted by “two well-known Communists” and pointed out that “he had shared a bunk with the two men in a concentration camp for five years.” Although the misgivings abated, it is still not clear whether they were totally dispelled. Stauffenberg, at any rate, seems to have favored a meeting.45

The next day, June 22, Leber and Reichwein went to meet two members of the central committee of the Communist Party, Anton Saefkow and Franz Jacob, in the apartment of a Berlin physician. When they arrived, however, they found that Saefkow and Jacob were accompanied by a third man, who had not been mentioned in the agreement. More disturbingly, one of the Communists greeted Leber by his full name, though this, too, ran counter to their agreement. Leber must have regarded their salutations as a sort of kiss of Judas. In any case, he apparently realized immediately that the meeting was a terrible mistake that posed an enormous danger not only to him but to the entire conspiracy, just as it was gathering its strength for another, perhaps final attempt on Hitler’s life.

Although both sides had previously agreed to meet again on July 4, Leber did not attend. Reichwein showed up alone and was arrested along with Saefkow and Jacob. The next morning the Gestapo nabbed Leber in his apartment.

By this time the war was entering its final phase. On June 6, 1944, the Allies had begun their invasion of Normandy. Just over two weeks later they had firmly established a beachhead and shipped one million men, 170,000 vehicles, and over 500,000 tons of materiel across the Channel. What is more, on June 22 four Soviet army groups, outnumbering the Germans six to one, broke through the thin, porous line of Army Group Center between Minsk and the Beresina River. They drove deep behind the German positions, isolating three pockets con taining twenty-seven German divisions-far more than at Stalingrad-which they surrounded and quickly destroyed.

Henning von Tresckow, who had been restored to his position as chief of general staff of the Second Army on the southern flank of Army Group Center, was once again pressing for immediate action against Hitler. Stauffenberg had always believed that the invasion of France was a point of no return, alter which a coup would be only a futile gesture any hope for a negotiated “political” settlement would die. The fear of having arrived on the scene too late dominated all his thoughts and made him extremely impatient.

Stauffenberg sent Tresckow a message through Lehndorff asking whether there was any reason to continue trying to assassinate Hitler now, since they had missed their last opportunity and no political purpose would any longer be served. Lehndorff returned promptly with Tresckow’s response, which signaled a final break from all concern with external circumstances, which had so often paralyzed the conspirators, as well as from political goals of any kind: “The assassination must be attempted,

8. THE ELEVENTH HOUR

On July 1 Stauffenberg was promoted to the rank of colonel and simultaneously assumed his new duties as chief of staff to the commander of the reserve army. General Fromm had always been a vigilant, cautious, opportunistic man, whose suspicions that Stauffenberg and Olbricht were plotting a coup had long since hardened into certainty. It seems all the more curious, therefore, that he went to such lengths to have Stauffenberg appointed to his staff. Fromm may simply have wanted to use Stauffenberg, who had written a re port that drew extremely laudatory reviews from Hitler, to escape the disfavor into which he had himself fallen. “Finally a general staff officer with imagination and intelligence!” Hitler is said to have remarked.1 It is also possible that Wehrmacht adjutant General Rudolf Schmundt recommended the brilliant young officer-who had been widely noticed and even considered as a possible successor to General Adolf Heusinger, the chief of operations-in the hope of reviving Fromm, who had “grown tired.” In any case, when Stauffenberg first met with his new boss and intimated that he was indeed considering a coup, Fromm merely thanked him for his frankness and let the matter drop. Stauffenberg’s successor on Olbricht’s staff was Colonel Albrecht Mertz von Quirnheim, whom Stauffenberg had known since their days together at the War Academy.2

Of crucial importance to Stauffenberg and to Olbricht, who now had to do without Stauffenberg’s services, was the fact that the new position gave Stauffenberg the access to Hitler that the conspirators had long sought. No longer would they need to arrange presentations of new uniforms or other difficult events. On June 7, the day after the Allied invasion of Normandy, Stauffenberg had already accompanied Fromm to a discussion at the Berghof, Hitler’s Obersalzberg headquarters. Stauffenberg recalled that Hitler seemed “in a daze,” pushing situation maps back and forth with a trembling hand and casting repeated glances at him.3 Now, barely one week after his new appointment, Stauffenberg found himself back at the Berghof once again.

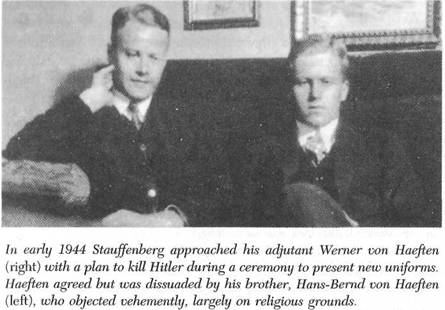

It is not clear whether he intended to assassinate Hitler then, but he did take a bomb with him and the other conspirators were warned in advance. It had always been assumed in resistance circles that Goring and Himmler would also have to be killed in any attack on Hitler. As things turned out, they were not present at this meeting, which may explain why Stauffenberg did not set off the bomb. It may also be, however, that he was still counting on Helmuth Stieff, whom he went to see when he learned that Stieff would preside at the following day’s long- postponed presentation of new uniforms at Schloss Klessheim-an occasion identical to the ones at which Bussche and Kleist had planned to blow themselves up with Hitler half a year earlier. But when Stauffenberg informed Stieff that he had brought “all the stuff along,” Stieff declined the mission.

This response reinforced Stauffenberg’s resolve to carry out the assassination himself. Upon learning of his new appointment in June, he had begun accustoming himself to the idea-over the objections of Beck-and had informed Yorck and Haeften of his intention. No one had ever proposed that Stauffenberg himself be the one to kill Hitler, both because of his severe war wounds and because the plans for a coup made his presence in Berlin indispensable. In view of what he termed “our desperate situation,” however, he decided that there was no other way. In early July he began to make the necessary preparations (arranging, above all, for an airplane to fly him back to Berlin) and to think through the changes that would have to be made to the plan to accommodate his dual role as assassin and leader of the uprising in the capital.