It is revealing that Stauffenberg’s decision to take so much upon himself raised no practical objections from the other conspirators, though it considerably increased the hazards of their undertaking. Only the surgeon Ferdinand Sauerbruch advanced serious reservations following a meeting held at his house. Stauffenberg, who had stayed behind, told him about what was planned, at least in part. Sauerbruch’s qualms at first focused on Stauffenberg’s still seriously weakened physical condition but ultimately broadened to include many other concerns as well.4

Stauffenberg’s fellow conspirators, by contrast, were troubled once again mostly by deep philosophical concerns. In lengthy discussions running from early spring until June, Stauffenberg finally managed to assuage the theological and ethical objections that Yorck and other members of the Kreisau Circle had to killing Hitler. He made especially great strides in this regard when he was able to confront the “hairsplitting scholars of the loyalty oath” with evidence of orders from Kaltenbrunner prescribing “’special treatment’ for 40,000 or 42,000 Hungarian Jews in Auschwitz.”5 Nevertheless, Hans-Bernd von Haeften wrestled to the very end with his anxieties about assassination, tied in knots as he was by professional codes of honor, ethical maxims, and, most important, religious strictures. When, early in the year, his brother Werner returned from a meeting with Stauffenberg and announced that he had agreed in principle to be the assassin the conspirators needed, Haeften asked: “Are you absolutely sure this is your duty before God and our forefathers?” But then, as the daily toll of the dead and injured mounted, he was tormented by the thought that he had dissuaded his brother and saved Hitler.6

Hans-Bernd von Haeften thus became entangled in a hopeless web of philosophical and religious reflection. His confusion can be seen in the solution he ultimately embraced: that Hitler ought to have been killed

Stauffenberg, on the other hand, considered the oath of loyalty to have been invalidated countless times. His religious and ethical beliefs led him to the conclusion that it was his duty to eliminate Hitler and the murderous regime by any means possible. His friends recalled that in the days and weeks preceding the assassination attempt he liked to recite Stefan George’s poem “The Antichrist,” which speaks in broad, phantasmagoric images about the chaotic confusion of senses and reason that ushers in and accompanies the Antichrist’s ascension. Although Stauffenberg was a great admirer of George, he always had an eye for simpler, rougher truths, and he led the debate within the resistance back to the political realm where it really belonged. Germans found themselves in a position, he argued, where they must inevitably commit some crime-either of commission or of omission. A few days before July 20 he added: “It’s time now for something to be done. He who has the courage to act must know that he will probably go down in German history as a traitor. But if he fails to act, he will be a traitor before his own conscience.”7

Speed was of the essence, although no longer just for military reasons. The so-called western solution, which called for the withdrawal of all German forces from France so as to strengthen the defense against the Soviets in the East, raised unrealistic hopes for Germany’s strategic situation. Goerdeler, for one, volunteered to go to France, possibly accompanied by Beck, and use his talents of persuasion to convince the German commanders there to offer Eisenhower a truce and open the front, allowing the Western Allies to pour into the heart of Germany. Goerdeler envisioned an unconditional surrender to the Western Allies as not only saving the country from the advance of the Red Army but, more important, forestalling what he later called the “ill-starred assassination attempt.” This, as it turned out, would be the last political proposal of Goerdeler’s life.8 Stauffenberg, too, had pondered the plan and, though tempted, discarded it as impracticable. Beck also distanced himself from any such endeavor. Hopes for a negotiated peace therefore faded to a faint glimmer, which was completely obliterated when Otto John, a lawyer who worked for Lufthansa, reported from Madrid on July 11 that the British ambassador had reiterated that hostilities would end only with simultaneous and unconditional surrender on all fronts. There was no avoiding total military disaster.

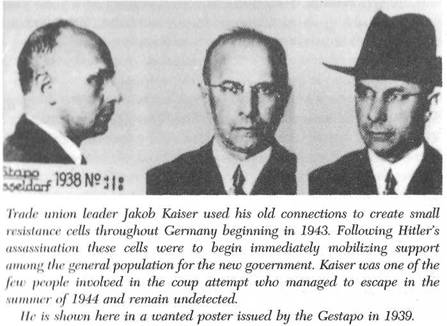

A far greater impetus to immediate action was the conspirators’ concern about being discovered. Their ever-widening circle could not escape detection by the Gestapo forever. Furthermore, Leuschner, Kaiser, and Max Habermann, the president of the German Office Workers’ Association, had been busy building an “invisible network” of opposition cells throughout Germany to provide broader support for the coup, which was being staged largely “from above.” As soon as the new government was installed, these cells were to whip up the public support and cooperation that would be essential to its success. But these preparations also increased the number of people who were initiated into the conspiracy.

On lop of this, in June news of the death sentences pronounced for Nikolaus von Halem, Mumm von Schwarzenstein, Otto Kiep, and other members of the Solf Circle had filtered down. At the same time the Gestapo arrested Colonel Wilhelm Staehle, a close contact of Goerdeler’s. In early July Leber and Reichwein were arrested. No one could be sure how much police interrogators managed to pry out of them, but everyone knew, as a number of diarists noted, that the air in Berlin was thick with furtive confidences and hushed but unambiguous understandings. The nervous strain of all the months of waiting began to take its toll. Military Intelligence captain Ludwig Gehre, for instance, panicked and threatened “to blow that whole nest on Bendlerstrasse sky-high” if he fell into the hands of the Gestapo. Stauffenberg was under enormous pressure to move quickly, but it was above all the arrest of Leber that motivated him to take action. “I’ll get him out. I’ll get him out,” Stauffenberg assured those around him on numerous occasions, and he also wrote Frau Leber saying, “We know where our duty lies.”9

On July 11 Stauffenberg was once again at Fuhrer headquarters on the Obersalzberg and once again he was carrying a bomb. He had summoned Goerdeler to Berlin to wait at the ready and had also informed others, including Witzleben, General Hoepner, Yorck, Count Helldorf, and a number of young officers in the Ninth Potsdam Reserve Battalion. Nevertheless, this day had the feel of a test run because many preparations that would have been necessary for the coup that was to follow the assassination were left undone. Furthermore, Himmler failed to show up yet again.

Stauffenberg’s patience was wearing thin. Just before the conference was to begin, he asked Stieff, “My God, shouldn’t we do it?” But Stieff pointed out Himmler’s absence, thereby imposing, perhaps unwittingly, another difficult condition on an assassination attempt that he himself was still not prepared to carry out. In the end Stauffenberg abandoned his plan and decided not to detonate the bomb he had taken along. When the news reached Berlin, Goerdeler commented, “half laughing and half crying, ‘They’ll never do it!’ ”10

Three days later, Stauffenberg was ordered to report for another meeting, on July 15, this time at the Wolf’s Lair, where Hitler had returned even though-or perhaps because-Russian forces were now only about sixty miles from the East Prussian border. Stauffenberg used the intervening time to review some of the technical and personnel details that would be crucial to the success of the coup. An agreement had been reached with General Erich Fellgiebel, the chief army signal officer, to interrupt signal traffic to and from Hitler’s headquarters at a given moment. But Fellgiebel had pointed out on several occasions that little could be done in advance because although there was a central communications center, the army, the air force, the SS, and the Foreign Office each had their own signal lines. In addition, care would have to be taken not to cut off signals to and from the troops at the front. Thus, Fellgiebel maintained, Fuhrer headquarters could only be isolated for a limited period; everything depended, he said, on doing exactly the right thing at exactly the right time. Meanwhile, however, improvements were to be made in communications with the liaison officers in the military districts, whose cooperation would be so essential to Operation Valkyrie; the preparedness of the army units in the Berlin area to take fast action had to be ensured; and numerous other aspects of mobilization, which were largely in Olbricht’s hands, needed to be clarified. The final problem facing Stauffenberg was how to handle the pliers for igniting the bomb, which had to be specially constructed for him because of his mutilated hand.

The statements to be made to the public were also checked again. A number of versions are still extant, all of them rough drafts or working copies that contain repetitions and contradictions. Apparently the conspirators