Some have claimed that both charges would have been too bulky and heavy to carry into the briefing room unobtrusively. This argument is hardly convincing, however, as the bombs weighed only about two pounds each, and Haeften had carried them both around in his briefcase earlier without any problems.

Stauffenberg was certainly nervous, and Vogel’s sudden appearance in the room must have given him a fright, but the most probable explanation for his bringing only the one bomb is that he was not fully aware of how such explosives work. Believing that a single bomb would suffice, he probably did not adequately consider the cumulative effect of two bombs. It may be that the second charge was only taken along as an alternative in the event that something went wrong, especially since the two timers were set differently, one for ten minutes and the other for thirty. What is clear, according to all experts, is that inclusion of the second charge, even without a detonator, would have magnified the power of the blast not twofold but many times, killing everyone in the room outright.1

Together with General Buhle and Major Freyend, Stauffenberg hurried out of the OKW bunker, briefcase in hand. They crossed the three hundred and fifty yards to the wooden briefing barracks, which lay behind a high wire fence in the innermost security zone, the so-called Fuhrer Restricted Area. After declining for the second time Freyend’s offer to carry his briefcase, Stauffenberg finally turned it over to him at the entrance to the barracks, asking at the same time to be “seated as close as possible to the Fuhrer” so that he could “catch everything” in preparation for his report.

In the conference room the briefing was already under way, with General Adolf Heusinger reporting on the eastern front. Keitel announced that Stauffenberg would be giving a report, and Hitler shook the colonel’s hand “wordlessly, but with his usual scrutinizing look.” Freyend placed the briefcase near Heusinger and his assistant Colonel Brandt, who were both standing to Hitler’s right. Despite his efforts to edge closer to Hitler, Stauffenberg could only find a place at the corner of the table; his briefcase remained on the far side of the massive table leg, where Freyend had placed it. Shortly thereafter, Stauffenberg left the room whispering something indistinctly, as if he had an important task to attend to.

Once outside the barracks, he went back the way he had come, turning off before Keitel’s bunker and heading toward the Wehrmacht adjutant building to find out where Haeften was waiting with the car. In the signals officer’s room he found not only Haeften but Fellgiebel as well: as they stepped outside, Hitler was already asking for the colonel, and an irritated General Buhle set out to look for him. It was just after 12:40.

Suddenly, as witnesses later recounted, a deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward. Stauffenberg gave a violent start and simply shook his head when Fellgiebel asked with feigned innocence what the noise could possibly be, Lieutenant Colonel Ludolf Gerhard Sander hurried over to the two men to reassure them that it was common for “someone to fire off a round or for one of the mines to go off.” Meanwhile, a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down. The quiet that had suddenly descended was broken once again, this time by the sound of voices calling for doctors. Stauffenberg and Haeften climbed into the waiting car and ordered the driver to take them to the airfield. As they did so, a body covered by Hitler’s cloak was carried from the barracks on a stretcher, leading them to conclude that the Fuhrer was dead.2

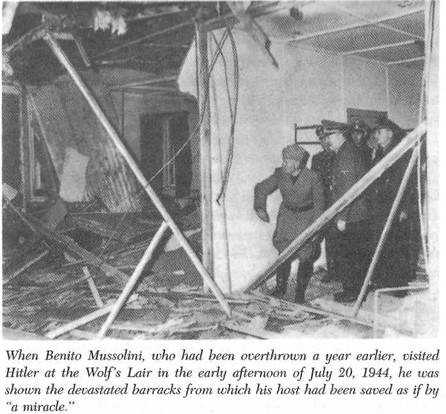

When the bomb exploded, twenty-four people were in the conference room. All were hurled to the ground, some with their hair in flames. Window mullions and sashes flew through the room. Hitler had just leaned far over the table to examine a position that Heusinger was pointing out on the map when his chair was torn out from under him. His clothing, like that of all the others, was shredded; his trousers hung in ribbons down his legs. The great oak table had collapsed, its top blown to pieces. The first sound to be heard amid all the smoke and devastation was Keitel’s voice shouting, “Where is the Fuhrer?” As Hitler stumbled to his feet, Keitel flew to him, taking him in his arms and crying, “My Fuhrer, you’re alive, you’re alive!”3 At this point, Hitler’s aide Julius Schaub and his valet, Heinz Linge, appeared and led the Fuhrer away to his nearby quarters.

In the meantime Stauffenberg and Haeften had reached the Restricted Area I guardhouse. The lieutenant in charge, having seen and heard the explosion, had already taken the initiative of ordering the barrier lowered, but recognizing the striking figure of Stauffenberg, he allowed the car to pass after a brief pause. More difficulty was encountered at the outer guardhouse on the way to the airfield. By this time an alarm had been raised and all entry and exit forbidden. The staff sergeant on duty was not about to be intimidated by Stauffenberg’s commanding bearing, and for a moment everything seemed to hand in the balance. Thinking fast, Stauffenberg demanded to speak by telephone to the commandant of Fuhrer headquarters, Lieutenant Colonel Gustav Streve, with whom he had a lunch appointment. Fortunately, he could only reach Streve’s deputy, Captain Leonhard von Mollendorff, who did not yet know why the alarm had been issued and therefore ordered the staff sergeant to allow Stauffenberg to pass. Halfway to the airfield, Haeften tossed the second package of explosives from the open vehicle. At about 1:00 p.m. the car reached the waiting airplane, and within minutes the conspirators took off for Berlin.

At just about this point, news of the blast reached army headquarters on Bendlerstrasse. Fellgiebel had taken steps about an hour earlier to block all signal traffic to and from both headquarters in Rastenburg, and he now received confirmation by telephone that this had been done While the communications blackout was certainly part of the conspirators’ plan, it would also have been a plausible reaction to the hastily issued instructions from Hitler’s staff that no news of the attack be allowed to reach the public. As a result, suspicion did not immediately fall on Fellgiebel, who soon had the amplification stations in Lotzen, Insterburg, and Rastenburg shut down as well. As Fellgiebel had frequently pointed out, however, it was technically impossible to cut the headquarters area off completely from the outside world.

As a result, Fellgiebel himself managed to put through a telephone call to the conspirators’ base of operations on Bendlerstrasse. But this call only caused more problems because the conspirators were faced with a situation that apparently none of them had foreseen and for which they had no code words: the bomb had gone off but Hitler had survived.

For the second time that day, then, General Fellgiebel found himself in a position to change the course of history. He basically had two options open to him. He could hide from Bendlerstrasse the fact that Hitler was alive and do everything possible to maintain the communications blackout of the Wolf’s Lair, resorting to violence if necessary. However hopeless it might seem, this ploy would help heighten the general confusion and at least keep the coup attempt going. The personal risk he would run by taking this course was not particularly great, as his fate would be sealed in any case if the coup failed. On the other hand, he could tell Bendlerstrasse that Hitler had survived and try to abort the coup attempt, at least the communications component, before it had really gotten under way. After all, he understood better than anyone else the impossibility of maintaining a communications blackout under these circumstances.

In the end, however, Fellgiebel hit on a third course. He informed his signal corps chief of staff at Bendlerstrasse, General Fritz Thiele, a fellow conspirator, that the assassination had failed but gave him to understand that the coup should proceed nevertheless. He thus blew away the elaborate smoke screen shrouding the attempt to seize power and revealed it as a straightforward revolt. According to Stauffenberg’s biographer Christian Muller this was a “major psychological blunder.” By informing Bendlerstrasse of the true state of affairs, Fellgiebel left it to the weak-willed group assembled there to decide what to do, at least until Stauffenberg’s arrival.4 Shortly after 3:00 p.m., Fellgiebel’s order blocking signal traffic was rescinded by Himmler, who had been summoned to Rastenburg, and Hitler began to swing into action, inquiring how soon it would be technically possible for him to address the German people directly over all radio stations in the Reich.

Meanwhile the hunt for the would-be assassin was launched. Initial suspicions fell on the construction workers employed at Fuhrer headquarters. But then Sergeant Arthur Adam came forward to say that he had seen Stauffenberg leave the briefing barracks before the explosion without his briefcase, his cap, or his belt, but little attention was paid to this information at first. Lieutenant Colonel Sander even shouted at Adam that if he really harbored “such monstrous suspicions about so distinguished an officer” he should go directly to the Security Service (SD).5 Instead, Adam approached Martin Bormann, who took him to see Hitler. One piece of evidence quickly led to the next, leaving little doubt among the Fuhrer’s confederates that Stauffenberg was the culprit. They did not yet realize, however, the enormity of the conspiracy or that a coup d’ etat was under way in Berlin.