Shortly alter hearing of the attack, Himmler had ordered the head of the Reich Security Headquarters (RSHA), Ernst Kaltenbrunner, and the superintendent of police, Bernd Wehner, to fly from Berlin to Rastenburg to take over the political and technical investigation of the assassination attempt. When Wehner arrived at Berlin’s Tempelhof airport, the plane was ready for takeoff. The waiting Kaltenbrunner, who was not privy to the latest information, stunned his companion by announcing, “The Fuhrer is dead!” Before the superintendent could regain his composure, Kaltenbrunner asked calmly whether he might like to play a few games of skat to while away the time.6

Somewhere in the skies between Berlin and Rastenburg the two planes must have crossed paths. It is not difficult to imagine the emotions Stauffenberg must have been feeling or the questions racing through his mind, in contrast to the icy calm of his adversary in the other plane. Having succeeded in igniting a bomb at Hitler’s feet-the event that had always been thought of as the “initial spark” that would touch off the great upheaval by which the entire Nazi regime would be overthrown-he now found himself condemned to more than two hours of anxious waiting. He could only pin his hopes on others: on Olbricht and Mertz, who alone held the levers of power; on reliable friends like Yorck, Hofacker, Schwerin, and Schulenburg, as well as on Jager, Hoepner, Thiele, Hase, and many others, including the liaison officers in the military districts. He could only assume that orders would be followed unquestioningly down the chain of command-perhaps even with the acquiescence of General Fromm- alter Olbricht issued the Valkyrie II code word.

The reality that awaited him was far different. As his plane neared Berlin, the coup had not advanced at all. Fellgiebel’s indecisive and rather vague message—“something terrible has happened: the Fuhrer is alive”—left Thiele unsettled and confused. To clear his mind he decided abruptly to go for a walk, apparently without bothering to inform Olbricht, and for nearly two hours he was nowhere to be found. Olbricht, too, had received a telephone call, probably around 2:00 p.m., from General Wagner in Zossen, and in view of the puzzling information from Rastenburg, they agreed not to act for the time being. After all, Fellgiebel’s message might have meant that the bomb had failed to go off or that Stauffenberg had been discovered and arrested, or that he was fleeing or that he had already been shot. Just five days earlier, Olbricht had issued the Valkyrie orders prema turely, and he knew that any repetition of that fiasco was bound to be fatal. This time, furthermore, in contrast to July 15, Fromm was present and would have to be dealt with.7

As a result, precious hours slipped away. Thiele returned around 3:15 p.m. and, after another conversation with Rastenburg, reported that there had been an “explosion in the conference room” at Hitler’s headquarters, which had left “a large number of officers severely wounded.” He thought that his source at Rastenburg may have “implied between the lines” that the Fuhrer was “seriously injured or even dead.” This was what prompted Olbricht and Mertz to decide finally to take the decisive step of issuing the Valkyrie orders, on their own initiative if necessary.8 Shortly thereafter, Haeften telephoned from the airport to announce that he and Stauffenberg had just landed, the attack had been successful, and Hitler was dead. When Hoepner suggested that the conspirators at Bendlerstrasse should wait for Stauffenberg to arrive, Olbricht retorted indignantly that there was no more time to lose. He got the deployment orders out of the safe for Fromm to sign. Meanwhile, Mertz called the senior officers of the Army Office together and informed them that Hitler had been assassinated. Beck would take over as head of state, he continued, while Field Marshal Witzleben would assume all executive func tions of the commander in chief of the Wehrmacht. Major Harnack was ordered to issue Valkyrie II to all military districts; to the city commandant, General Paul von Hase; and to the army schools in and around Berlin. It was shortly before 4:00 p.m.

Everything now depended on Fromm. But when Olbricht approached him to report that the Hitler had been assassinated, and asked him to give the orders to implement Operation Valkyrie, Fromm hesitated at the very mention of the word. He had received an official reprimand from Keitel for the alert issued on July 15 and was worried lest he fall back out of favor with Hitler, having just returned to his good graces. He therefore telephoned Keitel to ask whether the rumors in Berlin about the death of the Fuhrer were true. The OKW chief replied that an assassination attempt had been made but that Hitler had escaped with only minor injuries. Where exactly, he wanted to know, was Fromm’s chief of staff, Colonel Stauffenberg? Fromm answered that the colonel had not yet returned, and he hung up. He decided simply to do nothing.

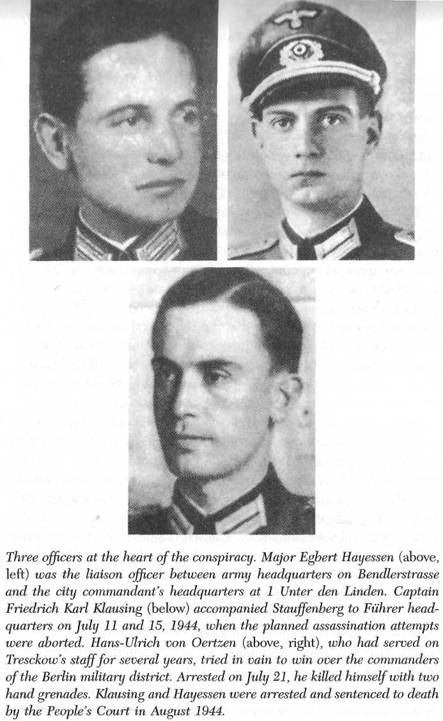

It is not clear whether Olbricht had already sent the orders for Valkyrie II out over the lines before he went to see Fromm. At this point he presumably still thought that Hitler was dead, and he had good reason to expect that Fromm could be won over. When he returned to his office to announce, “Fromm won’t sign,” he discovered that Mertz had plunged feverishly ahead, carrying the plans a step further. Although “Olbricht had once again grown hesitant,” he was “stampeded” into continuing.9 Captain Karl Klausing already had his orders to secure army headquarters; four young officers, Georg von Oppen, Ewald Heinrich von Kleist, Hans Fritzsche, and Ludwig von Hammerstein, had been summoned from the Esplanade Hotel to serve as adjutants; and Major Egbert Hayessen had already set off for the city commandant’s offices. Olbricht now leapt in, helping to organize matters and speed them along. He contacted the other commanders who were privy to the coup and called General Wagner in Zossen and Field Marshal Kluge in La Roche-Guyon, while Klausing was asked to send off the teleprinter message that began: “The Fuhrer Adolf Hitler is dead! A treacherous group of party leaders has attempted to exploit the situation by attacking our embattled soldiers from the rear in order to seize power for themselves!” Klausing finished typing and handed the message to the signal traffic chief, Lieutenant Georg Rohrig, but Rohrig immediately noticed that it did not contain the usual secrecy and priority codes. He chased after Klausing, reaching him at the end of the hall, and inquired whether the message should not have the highest secrecy rating. Without much thought, Klausing replied with a nervous “Yes, yes,” a decision that would have enormous unforeseen consequences. For only four typists were available at Bendlerstrasse who were cleared to send secret teleprinter messages, and it took them close to three hours to transmit the text. Without the secrecy requirements, the messages could have been sent out at much greater speed over more than twenty teleprinter machines.

The first message had barely begun to be transmitted when Klausing reappeared in the traffic office with another. It consisted of a number of instructions that hinted at the true nature of Valkyrie. The new communique ordered not only that all important buildings and facilities be secured but also that all gauleiters, government ministers, prefects of police, senior SS and police officials, and heads of propaganda offices be arrested and that the concentration camps be seized without delay. Following an injunction to refrain from acts of revenge came the sentence that unmasked the real intentions of the conspirators: “The population must be made aware that we intend to desist from the arbitrary methods of the previous rulers.”10

Since this message bore Fromm’s name, the conscientious Olbricht felt obliged once again to go and seek the consent of the chief of the reserve army. Hitler was truly dead, he assured Fromm, informing him that therefore “we have issued the code word to launch internal disturbances.” Fromm jumped to his feet. “What do you mean ‘we’?” he bellowed indignantly. “Who gave the order?” he shouted, insisting that he was still the commander. Olbricht said that Mertz was responsible, and Fromm ordered that the colonel be brought to him immediately. When Mertz confirmed what he had done, Fromm replied, “Mertz, you are under arrest!”

On the way back to his office, Olbricht peered out through a window overlooking the courtyard and saw Stauffenberg’s car pull up. It was 4:30 p.m., almost four hours after the explosion in the Wolf’s Lair. Stauffenberg gave Olbricht a short, hurried report on the assassination, and the two men decided to return together to see Fromm. Stauffenberg insisted once again that Hitler was dead: he had witnessed the explosion himself and had seen Hitler being carried out on a stretcher. Fromm remarked that “someone in the Fuhrer’s entourage must have been involved,” to which Stauffenberg coolly responded, “I did it.”

Fromm was flabbergasted, or at least seemed to be. With mounting rage, he told Stauffenberg that Keitel had just assured him the Fuhrer was alive, to which Stauffenberg replied that the field marshal was, as always, lying through his teeth. Unconvinced, Fromm asked Stauffenberg whether he had a pistol and, if so, whether he knew what to do with it at a moment like this. Stauffenberg said he did not have a pistol and in any case would do nothing of the sort, adding that the attack on Hitler was not the final goal but merely the first strike in a general insurrection. Unimpressed by this news, Fromm turned to Mertz von Quirnheim and ordered him to get a pistol. Mertz replied astutely that since Fromm had taken him into custody he could not carry out orders.

With mounting anger, Fromm now declared that Olbricht and Stauffenberg were under arrest as well. But as if he had been waiting for these words to be uttered, Olbricht turned the tables on the general by informing