Blumentritt, and ordered the immediate cancellation of the measures. He then dismissed Stulpnagel from his position and calmly returned to dinner. The atmosphere now, according to one witness, was “eerie-as if in a morgue.”23 Once again Stulpnagel and Hofacker begged the field marshal to reconsider but all he would say was, “If only that swine were dead!” As they parted, he gave Stulpnagel a piece of well-intentioned advice: “Put on civilian clothes and disappear somewhere.”24

As Stulpnagel took his leave of Kluge, without a parting handshake, at around 11:00 p.m., the task forces in Paris were just setting out from the Bois de Boulogne. Quickly and without encountering resistance, they arrested some twelve hundred members of the SS and SD in their quarters near the Arc de Triomphe. They also took into custody both SS Obergruppenfuhrer Oberg and Security Service chief Knochen, who had first to be located in a nightclub and then summoned to return to his headquarters on avenue Foch. Meanwhile, in the courtyard of the Ecole Militaire, a detachment under the city commandant, Hans von Boineburg, was piling up sandbags for the expected executions. Lawyers on his staff had already drafted indictments accusing Himmler’s subordinates of deporting Jews, blowing up synagogues in Paris, and confiscating “enemy property” in contravention of all legal principles.25

Shortly after midnight Stulpnagel returned to his headquarters in the Hotel Majestic. Defying Kluge’s orders, he did not immediately release the arrested officials and troops. Instead he went to the Hotel Raphael next door, which served as the officers’ mess. The rooms were packed, and in the great din there was much clinking of glasses. Officers and their civilian co-workers-people who were privy to what was going on and people who had had no idea-were all celebrating the arrests and the apparently imminent end of the war. Suddenly a voice from the radio room rose above the general clamor, announcing that the Fuhrer was about to speak.

The room fell silent. Stulpnagel entered, took a few steps forward toward the radio, and then remained there, still as a statue, as Hitler began to speak. The Fuhrer raged about “a very small clique of ambitious, wicked, and stupidly criminal officers,” thanked Providence for his survival, and condemned the “coterie of criminal elements which is now being mercilessly rooted out.” One officer noted that Stulpnagel was under “tremendous tension” but “showed no sign of emotion as he stood there, his hands crossed behind his back, twisting his gloves.” When Hitler finished, Stulpnagel turned on his heels and strode from the room without a word.26

Outside he was informed that the commander in chief of Naval Group West, Admiral Theodor Krancke, was threatening to march on Paris with more than a thousand men to free the interned SS and SD troops. In addition, the Luftwaffe commander in Paris, General Friedrich-Karl Hanesse, had put his forces on alert. Then Stulpnagel’s chief of staff, Colonel Hans-Ottfried von Linstow, reported that Stauffenberg had called earlier in the evening to say that all was lost and that his killers were already prowling the hall outside his office. But still Stulpnagel did not give up. Even when notified that Kluge had put through his dismissal as military commander and that General Blumentritt was on his way to relieve him, he carefully considered his next move and even discussed with Hofacker and Finckh the possibility of forcing Kluge’s hand by taking the decisive and irreversible step of executing the SS commanders. In the end, though, Stulpnagel abandoned all hope and gave the order to release the prisoners. “Providence,” he said, “has decided against us.”27

With the release of the SS commanders, a very delicate and dangerous situation arose. It was handled with aplomb, however, by the reliable Hans von Boineburg. A small, bald man with a hoarse voice and a monocle, Boineburg proved that night that he was far more than the mere caricature of a German soldier whose persona he liked to affect, albeit somewhat ironically. He set out resolutely for the rue de Castiglione, where Oberg and Knochen were being held prisoner in a suite at the Hotel Continental. In his charmingly blunt manner he announced that they were now free to go and delivered to the outraged Oberg an invitation from Stulpnagel to return to the Hotel Raphael. Boineburg managed to mollify the SS commander to such an extent that he eventually agreed to come. Knochen, however, went back to his quarters.

A bizarre scene then unfolded in the Salon Bleu of the Hotel Raphael, as the conspirators and the executioners sat down together. Just minutes before, they had been deadly enemies, some planning the murder of the person next to them, others feeling stunned and vengeful, and all brimming with suspicion. In the halting conversation that ensued, each player was keenly aware that any misstep could easily spell the death of Stulpnagel, Boineburg, Hofacker, Linstow, and the other members of Stulpnagel’s staff on the one side or Am bassador Otto Abetz and SS Obergruppenfuhrer Oberg on the other, not to mention Knochen, Krancke, and Blumentritt, who joined the group somewhat later.

Stulpnagel had ordered a round of champagne in an effort to create a relaxed, friendly atmosphere despite the heavy shadow cast by recent events. Abetz arrived first, in an angry mood, but he had grown much more conciliatory by the time Oberg appeared soon afterward. Still uncertain as to how to proceed, Oberg immediately declared that “investigations” would have to be conducted. But Abetz intervened, managing to persuade the still- furious SS commander to shake hands with his adversary. Abetz assured Oberg that Stulpnagel had been given contradictory orders, and gradually he led the conversation toward the conclusion that, in view of the approaching Allied forces and the mounting threat from the French underground, Germans had no choice but to stand together, shoulder to shoulder.

Oberg, who of course suspected that Stulpnagel had known exactly what he was doing, was hardly deceived by the game that was being played. “So, Herr General,” Oberg said in response to Stulpnagel’s greeting, “you seem to have bet on the wrong horse.” Oberg also realized, however, that his own carelessness and imprudence would make him an object of scorn within the SS. He was therefore by no means immune to the attempts of the army commanders to paper over the entire affair. Thus, as the evening wore on, he grew more approachable, the conversation picked up, and an atmosphere of friendly camaraderie began to develop. Champagne flowed in great quantity, and by the time Blumentritt and his two aides arrived, those gathered, though still somewhat distrustful, seemed in remarkably good spirits-as if at “a party that was in full swing.”28

On his way to the Raphael, the ever-resourceful Blumentritt had hinted that a certain “arrangement” might be arrived at-a suggestion that was eagerly seized on by Knochen. Now Knochen reintroduced it, cautiously testing the waters by tentatively describing his notion, then retreating, then stating it a little more clearly, and then backing off behind a fog of words. Eventually he and Oberg decided to step outside for a moment. Back in the Salon Bleu, Blumentritt finally came out with the proposal, which everyone present seemed to find convincing except Admiral Krancke, who suddenly erupted in a tirade about “Stulpnagel, treason, and perfidy.” For a moment the whole fabric of half-truths seemed about to fall apart, but then opinion rallied around Blumentritt’s story of “mistakes” and “false alarms.” Considerably relieved, the partygoers returned to their champagne, drinking toasts to one another and celebrating into the early hours of the morning. The author Ernst Junger, who was on Stulpnagel’s staff, wrote of this day, “The big snake [Hitler] was in the bag, but then we let it out again.”29

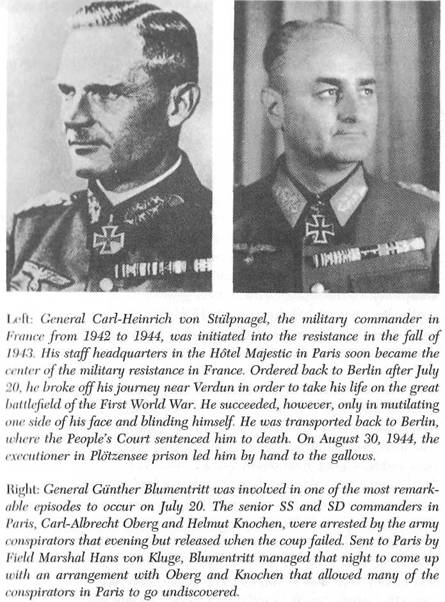

Stulpnagel presumably only participated in the game in an attempt to protect his staff, which had always gone along with Hofacker’s and his wishes. (In fact, a relatively large number of his officers did survive the ensuing purge.) For himself, Stulpnagel realized, there was no hope-even though he did not yet know that he had already been betrayed to Keitel by Kluge, who brushed Blumentritt’s astonishment aside with the comment, “Things will now take their course.” Early in the morning orders arrived from Keitel: Stulpnagel was to return to Berlin at once. He look leave of his colleagues and set out by car. Near Verdun, where he had fought in the First World War, Stulpnagel had his driver drop him off and proceed ahead a little. With Mort-Homme Hill rising before him, he climbed down the embankment of the Meuse canal. The report of a pistol split the air. Stulpnagel’s two traveling companions hurried back and dragged his body out of the swirling waters. He was still alive, having succeeded only in blinding himself. Nursed back to health under constant guard, Stulpnagel was arraigned before the People’s Court on August 30. He refused to name any accomplices, and when Roland Freisler, the judge, asked specifically about Rommel and Kluge he answered tersely, “I will not discuss the field marshals!” Later that day the executioner led the blind man to the gallows.30

Many factors led to the failure of the July 20 plot. Among those most frequently mentioned is the “amateurism” of the leading conspirators, insufficient planning, blind trust in the chain of command, and poor coordination among the participants, which led to the bedlam that broke out at army headquarters. As Admiral Canaris observed, not without a certain cynicism, to an acquaintance he met on the street two days later, “That,