debate with his adjutant, First Lieutenant Hellmuth Arntz, about the afterlife, which Fellgiebel did not believe in. When the long-awaited call came he replied simply, “I’m on my way.” Arntz asked if he had his pistol, but Fellgiebel said, “One doesn’t do that. One takes a stand.”1

The next day SS Obersturmbannfuhrer Georg Kiessel was appointed head of a special board of inquiry, which soon numbered four hundred people. Hitler held a briefing to announce guidelines for the judicial proceedings against those involved in the failed coup. Denouncing the conspirators as “the basest creatures that ever wore the soldier’s tunic, this riff-raff from a dead past,” he declared: “This time I’ll fix them. There will be no honorable bullet for… these criminals, they’ll hang like common traitors! We’ll have a court of honor expel them from the service; then they can be tried as civilians…. The sentences will be carried out within two hours! They must hang at once, without any show of mercy! And the most important thing is that they’re given no time for any long speeches. But Freisler will lake care of all that. He’s our Vishinsky.”2

As the days passed, the number of suspects grew larger and larger. Witzleben was among the first to be arrested. Popitz was picked up in his apartment at about five o’clock on the morning of the twenty-first and was soon followed by Oster, Kleist-Schmenzin, Schacht, Canaris, Wirmer, and many others. Only shortly before July 20 the Gestapo officials responsible for surveillance of the military had reported no particular activity, noting only in passing a certain “defeatism” in the circles around Beck and Goerdeler.3 That was the reason Hitler apparently believed at first that the attack was the work of a “very small clique of ambitious officers,” as he said in his radio address to the German people. Now, to the astonishment of virtually everyone, it turned out that Stauffenberg and his immediate accomplices represented only the tip of the iceberg. The conspiracy extended far beyond the army to civilian circles on both sides of the political spectrum, even to groups presumed to be close to the Nazi Party.

On the evening of July 20 an overly confident Count Helldorf had averred that the police would not dare lay a finger on him. In fact, the investigators hardly hesitated before pouncing. Other conspirators, like General Eduard Wagner, escaped their fates by committing suicide. Major Hans Ulrich von Oertzen, who had urged the military district headquarters on Hohenzollerndamm to support the uprising, managed in the bedlam that surrounded his arrest to hide two grenades. Shortly before he was to be led away he held one to his head and detonated it. He collapsed on the floor, grievously wounded. With all his remaining strength, he dragged himself to where the second grenade lay hidden, shoved it in his mouth, and pulled the pin. Suicides such as this only extended the circle of suspects to include friends, relatives, and colleagues.

The code of personal honor, always a significant factor in the strange helplessness of the conspirators, influenced their behavior even in defeat. Very few conspirators actually attempted to escape. Most simply arranged their personal affairs and waited calmly for the knock on the door, ready, or so they believed, for anything that might befall them. Many refused to avail themselves of proffered hiding places or even asked to be arrested. Principally they wished to spare their friends and relatives interrogation by the police, but most of them were also operating out of the categorical morality that was the bedrock ol their thinking. “Don’t flee-stand your ground!” was how Karl Klausing rationalized his decision to give himself up; he did not want, he said, to leave his captured comrades in the lurch. Schlabrendorff also refused to flee, as did Trott, evidently “on account of his wile and children.” Tresckow’s brother Gerd knew about the conspiracy, but as a lieutenant colonel in a division on the Italian front he was too far away from the scene to arouse suspicion. Nevertheless, he went and confessed to his superior officers and, when told lo forget about it, insisted on his culpability. He was finally arrested and incarcerated in the Gestapo prison on Lehrterstrasse, where, in a state of physical and mental depletion, he took his life in early September 1944.4

Time and again, fugitives sought by the police turned themselves in out of a feeling that can best be described as part pride and part exhaustion. They were no longer willing or able to hide out or to continue the duplicitous life they had led for far too long, at the cost, they believed, of their self-respect. Ulrich von Hassell left his home in Havana and traveled to Berlin by a circuitous route, making many stops. For a few days he roamed restlessly through the streets of the capital, then went to his desk and waited calmly for the Gestapo to arrive. Theodor Steltzer, who was already in Norway, refused to flee across the border to Sweden, returning instead to Berlin, where he acted on his belief that a Christian cannot tell a lie, even to a Gestapo interrogator or before the People’s Court.5

The motivation behind these and many other unrealistic if honorable gestures was certainly the expectation that the impending trials could be used as a forum for denouncing the Nazis. As the curtains fell on their lives, these brave men hoped for one last chance to expose the true nature of the regime, much as some of them had fervently hoped to do in criminal proceedings against Hitler. The illusion that they would be allowed to speak their minds freely at their trials was soon shattered, however, as was the belief, cherished primarily by the military men, that every legal formality would be observed and that they would be treated in a manner befitting their standing in society.

Although the investigators found themselves groping in the dark at first over the next few months, they succeeded in arresting some six hundred suspects beyond those immediately implicated in the plot. A second wave of arrests in mid-August, known as Operation Thunderstorm, put five thousand putative opponents of the regime behind bars; most of these people had been connected to various political parties and organizations in the Weimar Republic. Again, even when under interrogation, some of the accused strove more to demonstrate the high moral principle behind their actions than to save their lives, so that the head of the special investigatory commission was soon able to say that “the manly attitude of the idealists immediately shed some light in the darkness.”6

Although much of this courageous and self-sacrificing spirit may seem naive, it was perhaps the only defense to which the regime had no answer. Apparently Hitler had originally intended to stage a great spectacle modeled on the Soviet show trials of the 1930s, with radio and film coverage and lengthy press reports, but he was soon forced to abandon all such plans. Schulenburg, for example, declared before the court: “We resolved to take this deed upon ourselves in order to save Germany from indescribable misery. I realize that I shall be hanged for my part in it, but I do not regret what I did and only hope that someone else will succeed in luckier circumstances.” Similar declarations from numerous defendants increasingly put the authorities on the defensive, and on August 17, 1944, Hitler forbade any further reporting of the trials. In the end, not even the executions were publicly announced.7

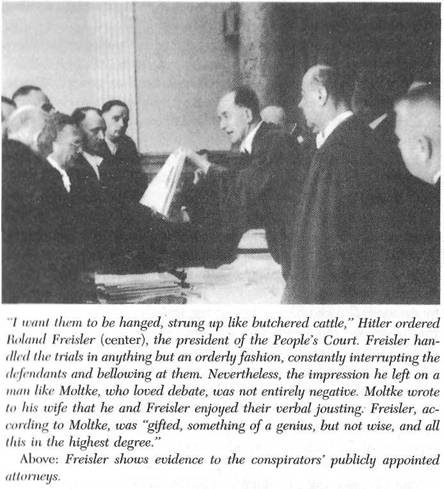

The Gestapo had considerable difficulty determining the breadth of the conspiracy. It is known, for instance, that Stieff and Fellgiebel held out for at least six days under torture without revealing anything. Contrary to legend, no list of conspirators or a projected cabinet was ever found, and as late as August 8 Yorck was able to tell prison chaplain Harald Poelchau that the Gestapo still knew nothing about the Kreisau Circle. Moltke’s name was not uttered until Leber’s interrogation on August 10.8 Schlabrendorff, who survived the war to write a detailed account of the four types of torture employed-beginning with a device to screw spikes into the fingertips and progressing to spike-lined “Spanish boots,” the rack, and other horrors-did not reveal the names of his co- conspirators at Army Group Center, even when the mutilated corpse of his friend Tresckow was exhumed and shown to him. Despite severe torments, not much more than was already known could be dragged out of Jessen, Langbehn, Oster, Kleist-Schmenzin, and Leuschner. But what these men refused to reveal in so-called intensified interrogation-in which all the horror and vengeful fury were brought to bear on them-the Allies now did. As if eager to do one last favor for Hitler, British radio began regularly broadcasting the names of people alleged to have had a hand in the coup. Roland Freisler, the president of the People’s Court, was even able to show Schwerin von Schwanenfeld an Allied leaflet that heaped scorn on the conspirators, just as the Nazis’ propaganda was doing.”

The military “court of honor” that Hitler had demanded met on August 4, with Field Marshal Rundstedt presiding and Field Marshal Keitel, General Guderian, and Lieutenant Generals Schroth, Specht, Kriebel, Burgdorf, and Maisel serving as associates. Without any hearings or presentation of evidence, they drummed twenty-two of ficers out of the Wehrmacht, thus depriving them of the legal protections of a court-martial, just as Hitler wanted. However extreme this step may have appeared to be, it was actually only the final act in a lengthy process that had revealed to all that the unity and cohesiveness of the army had long since been shattered. It was the last of many gestures of submission to Hitler’s will.

Responsibility for trying the accused officers and the other participants in the attempted coup fell now to the People’s Court, which had been specially constituted in 1934 to judge “political crimes.” Hitler ordered the cases to