among our forefathers.” One had only to read the Teutonic sagas, he said: “When they placed a family under the ban and declared it outlawed or when there was a blood feud in a family, they were utterly consistent… . This man has committed treason; his blood is bad; there is traitor’s blood in him, that must be wiped out. And in the blood feud the entire clan was wiped out down to the last member. And so, too, will Count Stauffenberg’s family be wiped out down to the last member.”17

Accordingly, Himmler ordered relatives of the Stauffenberg brothers arrested, from their wives all the way to a three-year-old child and the eighty-five-year-old father of a cousin. A third Stauffenberg brother, Alexander, was not involved in the plot but was nevertheless returned from Athens to Berlin, interrogated at length, and dispatched to a concentration camp. The property of all relatives was seized. After an interrogation that yielded nothing of interest, Countess Stauffenberg was sent to the Ravensbruck concentration camp, as was her mother. Her children were placed in an orphanage and given the new surname Meister, which had been dreamed up by the Gestapo, perhaps in an ironic allusion to the Stefan George circle, whose members referred to their mentor as “master.” Similar fates befell the families of Goerdeler, Tresckow, Lehndorff, Schwerin, Kleist, Oster, Trott, Haeften, Popitz, Hammerstein, and many others. While the persecution was extensive, it was also arbitrary: Princess Elisabeth Ruspoli, the mistress of General Alexander von Falkenhausen, was arrested, for example, but Moltke’s family was left largely undisturbed.

In the tumultuous weeks preceding the final collapse of the Third Reich, most of these family members and other “prominent” prisoners were gathered together and dispatched on a nerve-wracking odyssey from one concentration camp to the next. In the late afternoon of April 28, 1945, the convoy arrived in Niederdorf in the Puster valley of Tyrol. Under the watch of some eighty SS men the trucks disgorged, among others, Hjalmar Schacht; the former French prime minister Leon Blum and his wife; Franz Halder; Kurt von Schuschnigg, the last chancellor of Austria; Martin Niemoller; Falkenhausen; the former Hungarian prime minister Count Nicholas Kallay; a nephew of Vyacheslav Molotov; some British secret service men; and a number of generals from countries formerly allied with Germany-160 people in all. The convoy commander, SS Obersturmfuhrer Stiller, had top- priority orders to lead the prisoners to the nearby Pragser valley, where they would be shot and their bodies disposed of in the adjacent Wildsee. When one of the SS men disclosed to the throng that they were at “the final stop before the end,” panic broke out. In the midst of the ensuing pandemonium one of the prisoners, Colonel Bogislav von Bonin, managed to contact the general staff of the commander in chief in the Southwest, stationed in Bozen, who asked Captain Wichard von Alvensleben to investigate “what’s going on.” But Alvensleben took it upon himself to go much further. The next morning he showed up with a quickly assembled contingent of troops and freed the prisoners, much to the anger of his superiors.18

The investigation of the failed coup received new impetus and much new information when Carl Goerdeler was finally arrested on August 12. For three weeks devoted friends had kept him in hiding, largely in and around Berlin, despite the bounty of a million marks on his head. True to form, he wrote yet another report during this time, as if obsessed with a mission that would never end. After a long, exhausting period of vacillation over whether he should continue hiding or attempt to flee the country, he seemed to abandon all hope of survival and simply set out to see his West Prussian homeland one last time. After a perilous three-day journey and much camping out in the open forest, he managed to reach Marienwerder. On his way to visit the graves of his parents, however, he was recognized by a woman who followed him so doggedly that he was forced to turn back. After another night under open skies, he was so drained that in the morning he sought refuge at an inn. Here he was recognized again, this time by a Luftwaffe employee who at one time had frequented his parents’ house. She denounced Goerdeler to the police, apparently more out of eagerness to be involved in important goings-on than out of any particular ill will toward Goerdeler or even desire for the million-mark reward.

In the very first sentence he uttered in his initial interrogation session, Goerdeler admitted involvement in planning the coup. But he was eager to distance himself from the attempt on Hitler’s life, describing Stauffenberg’s failure as a “judgment by God.” A few days after the attempt he had admonished an acquaintance he encountered in a Berlin metro station with the words “Thou shalt not kill.”19 Otherwise though, he spoke volubly about the leading role he had played in the opposition and about the widespread involvement of civilians, all to the great astonishment of his interrogators, who had continued to imagine that they were dealing with a military putsch and now learned for the first time about the civilian aspect-from no other authority than Goerdeler himself.

The willingness with which the former mayor of Leipzig disclosed the names of implicated businessmen, union leaders, and churchmen and detailed their motives and goals made him a traitor in the eyes of many of his fellow prisoners. It has also posed unsettling questions for his biographers. But one needs to make allowances for the shock he felt on being imprisoned, for his shattered nerves, and for the fact that he was held, heavily chained, in solitary confinement far longer than any of the other prisoners. He was dragged through endless interrogations and forced to pass night after night under brilliant floodlights, the door to his cell open and a guard posted outside; still, he did not recant his devotion to the cause. In the notes he wrote during these weeks he described Hitler as a “vampire” and a “disgrace to humanity,” referred to the “bestial murder of a million Jews,” and lamented the cowardice of those who allowed such things lo happen “partly without realizing it and partly out of despair.”20 There were numerous friends and co-conspirators whom Goerdeler actually saved from arrest, and it is likely that he was also attempting to confuse the Gestapo by inundating them with an avalanche of facts and details.

Primarily, though, Goerdeler was simply acting in accordance with his lifelong belief that truth and reason would prove persuasive, even to Gestapo agents. This time, however, his belief would cost many lives. Thinking that the special commission must already know the general outlines of the plot, Goerdeler never thought to mini mize things, to portray the monumental efforts of the resistance as merely the ravings of a few disgruntled malcontents. He still believed he had a duty to open Hitler’s eyes to the fact that he was leading Germany into the abyss; he may even have hoped to initiate a dialogue with him. Goerdeler’s “extraordinarily far-reaching account,” as described in the Kaltenbrunner reports, thoroughly rebutted Hitler’s notion of a “very small clique of ambitious officers.” Goerdeler’s candor was as admirable as it was fatal. His biographer Gerhard Ritter comments: He wanted not to play down what had been done but rather to make it appear as large, significant, and menacing to the regime as possible. For Goerdeler, this was absolutely not an officers’ putsch… but an attempted uprising by an entire people as represented by the best and most noble members from all social strata, the entire political spectrum, and both the Catholic and Protestant churches. He himself stood up valiantly for what he had done, and he presumed his friends would do the same. In the shadow of the gallows, he still thought only of bringing the entire, unvarnished truth to light and hurling it in the faces of the authorities. This was impossible at the public show trials, as the shameful proceedings against Field Marshal Witzleben had made chillingly apparent. And so Goerdeler sought to speak out all the more clearly, forcefully, and exhaustively in the interrogations.21

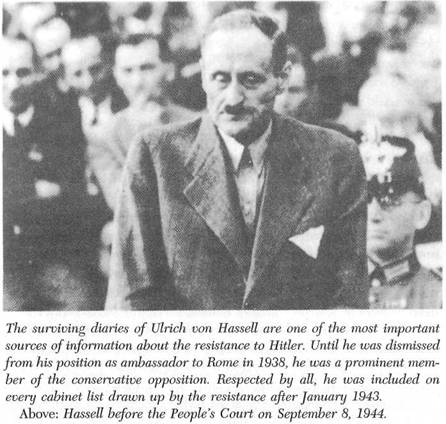

The futility of this gesture, on which he had apparently based great hopes, was made clear to him scarcely four weeks after his incarceration at Gestapo headquarters on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse. On September 8 he stood before the People’s Court with Ulrich von Hassell, Josef Wirmer, lawyer Paul Lejeune-Jung, and Wilhelm Leuschner. Their trials proceeded like all the rest, with a raving, wildly gesticulating Freisler constantly interrupting and refusing to allow any of the accused to explain their motives. In the end Goerdeler was con demned as a “traitor through and through,… a cowardly, disreputable traitor, consumed with ambition, and a political spy in wartime.” While Wirmer, Lejeune-Jung, and Hassell were executed that same day and Leuschner was dispatched two weeks later, Goerdeler was kept alive for almost five months. He was probably spared so that further information could be extracted from him and so that his skills as a master administrator could be exploited for drawing up plans for reform and reconstruction after the war. The decisive factor in the delay, however, was presumably Himmler’s desire to have Goerdeler as a negotiator in the event that his insane scheme of making contact with the enemy behind Hitler’s back succeeded. This supposition is supported by the fact that Popitz’s life was also spared for some time, even though he had been sentenced to die on October 3.22

Goerdeler hoped that his date with the executioner would be delayed until the war had ended, saving him and his fellow prisoners. Meanwhile, however, the Allied advance into central Germany was stalled, and Justice Minister Otto Thierack began asking more and more pointed questions as to why Goerdeler and Popitz were still alive. Like so many of his previous fantasies, Goerdeler’s last hope finally burst on the afternoon of February 2, 1945, when bellowing SS men barged into his cell and led him away.