be heard in closed chambers before a small, select audience. He invited Freisler and-if the reports are accurate- even the executioner to Fuhrer headquarters, where he instructed them to refuse the condemned men all religious and spiritual comfort. “I want them to be hanged, strung up like butchered cattle,” Hitler said.10

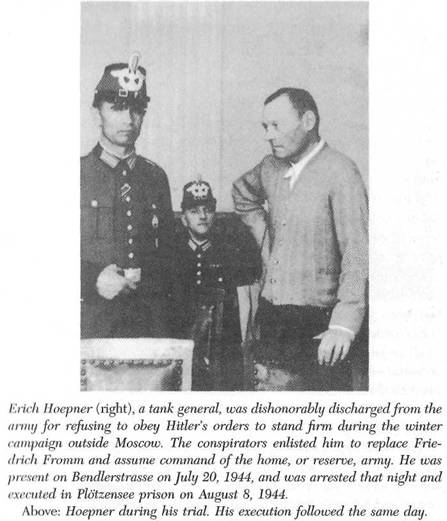

The trials began on August 7 in the great hall of the Berlin People’s Court, which was hung with Nazi flags for the occasion. The accused were Witzleben, Hoepner, Stieff, Hase, Bernardis, Klausing, Yorck, and Hagen. To further humiliate the conspirators, they were forbidden to wear neckties, and Witzleben was even denied suspenders for his trousers. Hoepner was dressed in a cardigan. All bore the signs, as one witness reported, of the “tortures they had suffered while in custody.”11 Presiding over the scene was Roland Freisler, attired in his red judicial robes and seated beneath a bust of the Fuhrer.

Freisler had been appointed president of the People’s Court two years earlier, and in him the regime found a man very much in its own image. Hitler always felt a certain distrust toward Freisler, however, and his likening of him to Andrei Vishinsky, the chief prosecutor In the Moscow show trials, suggests the reason: Freisler had been taken prisoner by the Russians during the First World War and had become a Soviet commissar after the October Revolution; he liked to boast that he had begun his career as a diehard Communist. With his cynical bent and taste for radical politics, he joined the Nazis in 1925, throwing himself into political and journalistic tasks on behalf of the party and reaping his reward with an appointment as state secretary in the Ministry of Justice. Seizing on a comment by Hitler in his address to the Reichstag justifying the Night of the Long Knives, he made himself a vocal advocate of

His loud, bullying style-intended, he occasionally conceded, to “atomize” the defendants-was matched by his theatrical temperament, his fondness for adopting extravagant poses, and his pleasure in exercising power over life and death. The psychological corollary to all this was his fawning subservience to Hitler. He played his roles to the hilt, outraged one moment, then cutting, then affable, now and again seeming to enjoy sharp-witted repartee. All in all he was the kind of man who rises to the top in turbulent times, when all values and principles are placed in doubt. The first chief of the Prussian Gestapo, Rudolf Diels, called Freisler “more brilliant, adaptable, and fiendish than anyone in the long line of revolutionary prosecutors.” Despite his repellent characteristics and the clear delight he took in humiliating and defaming those who appeared before him, few were immune to his remarkable charisma. Helmuth von Moltke wrote after his trial that Freisler was “gifted, something of a genius, but not wise, and all this in the highest degree.” According to Freisler’s predecessor, Otto Thierack, he was simply mentally ill.12

Freisler opened the first day of proceedings by remarking that the court would be ruling on “the most horrific charges ever brought in the history of the German people.” He heaped scorn on the accused, continually referring to them as “rabble,” “criminals,” and “traitors,” men with the “character of pigs”; Stauffenberg he called a “murderous scoundrel.” Freisler’s role was to express boundless moral outrage. The proceedings focused strictly on the deeds that had been committed; any attempt by the accused to introduce the issue of their motives was immediately interrupted. Stieff came before the court first, and when he tried to raise the issue Freisler informed him that as a soldier he needed only “to obey, triumph, and die, without looking either left or right” and added, “We don’t want to hear any more from you about that.” None of the accused was allowed an opportunity to address the court at length or even to reach any sort of understanding with their attorneys, who were seated some distance away. Not all but a good many of these attorneys openly supported the prosecution’s case. Witzleben’s lawyer, for instance, a Dr. Weissmann, stated in his final summation that the court’s decision had in effect already been rendered by “heavenly Providence when, in a miraculous act of deliverance, it protected the Fuhrer from destruction for the sake of the German people.” Weissmann concluded, “The deed of the accused stands, and the guilty perpetrator will go down with it.” Kreisler sentenced all eight defendants to be hanged, ending the proceedings with the words “We return now to life and to the struggle. We have nothing more in common with you. The

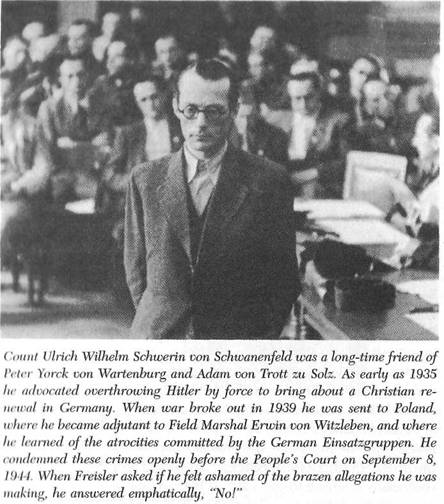

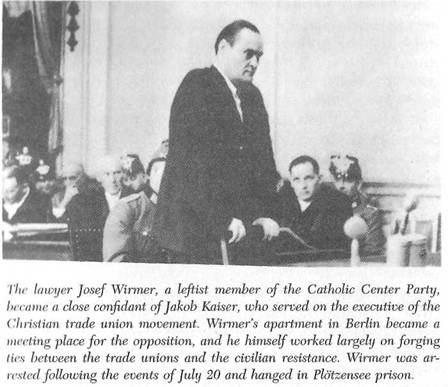

Thus the trials proceeded, case after case. The next session was held on August 10, when Fellgiebel, Berthold von Stauffenberg, Alfred Kranzfelder, and Fritz von der Schulenburg were paraded before the People’s Court. Freisler seemed particularly irritated by the quiet dignity and disdain of Schulenburg. Josef Wirmer was arraigned not long afterward. When Freisler remarked that Wirmer would soon find himself roasting in hell, Wirmer bowed curtly and riposted, “I’ll look forward to your own imminent arrival, your honor!” Freisler did not always succeed in interrupting the defendants in time. Hans-Bernd von Haeften managed to interject a comment about Hitler’s “place in world history as a great perpetrator of evil”; Kleist-Schmenzin announced that he had been determined to commit treason ever since January 30, 1933, and spoke of it as a “command from God”; Schwerin managed to mention “all the murders committed at home and abroad” and, when asked by an angry Freisler if he was not ashamed to be making such a base allegation, retorted, “No!” During the examination phase of the proceedings, Casar von Hofacker claimed that he had acted with as much right on July 20 as Hitler had on November 9, 1923, the day of the “beer-hall putsch.” He regretted, he said, that he had not been chosen to carry out the assassination, because then it would not have failed. Later he managed to cut Freisler off during one of the judge’s own numerous interruptions: “Be quiet now, Herr Freisler, because today it’s my neck that’s on the block. But in a year it will be yours!” Fellgiebel even advised Freisler that he had better hurry lest he himself hang before he hung the accused.14

On the afternoon of August 8, immediately following their trials, the first group of condemned men was transported to the execution grounds in Plotzensee prison. Although Hitler had expressly forbidden any spiritual consolation, the prison chaplain, Harald Poelchau, did manage to “speak quickly” with Witzleben and Hase. But according to his own report, as he approached Yorck “the conversation was violently interrupted. SS men with floodlights stormed into the cells and filmed the various prisoners before they were hauled away to be executed. The resulting movie, made at the express wish of the Fuhrer, was supposed to show all phases of the entire process, at length and in full detail.”15

Once inside Plotzensee, the prisoners were allowed only enough time to change into prison garb. One by one, in accordance with prison drill procedures, they crossed the courtyard in wooden shoes, under the ever- present gaze of a camera, and entered the execution chamber through a black curtain. Here, too, a camera recorded their every step as they arrived and were led to the back of the chamber to stand under hooks attached to a girder running across the ceiling. Floodlights brilliantly illuminated the scene. A few observers were standing around: the public prosecutor, prison officials, photographers. The executioners removed the prisoners’ handcuffs, placed short, thin nooses around their necks, and stripped them to the waist. At a signal, they hoisted each man aloft and let him down on the lightened noose, slowly in some cases, more quickly in others. Before the prisoner’s death throes were over, his trousers were ripped off him. After each execution the chief executioner and his assistants went to the table at the front of the room and fortified themselves with brandy until the sound of steps announced the arrival of the next victim. Every detail was recorded on film, from the first wild struggle for breath to the final twitches.

Hitler had already “eagerly devoured” the arrest reports, information on new groups of suspects, and the statements recorded by interrogators. Now, on the very night of the first trials and executions, the film of the proceedings arrived at the Wolf’s Lair for the amusement of the Fuhrer and his guests. The putsch, he announced to his assembled retinue, was “perhaps the best thing that could have happened for our future.” He could not get enough of watching his foes go to their doom. Days later, photographs of the condemned men dangling from hooks still lay about the great map table in his bunker. As his horizons shrank on all sides, Hitler took great satisfaction from this, his last great triumph.16

The excess so characteristic of the Nazi regime expressed itself not only in the savageness of the retribution but also in its broad sweep: even distant relatives of the conspirators fell victim to a lust for revenge worthy of the ancient Teutonic tribes. Himmler discussed the failed coup at length at a meeting of gauleiters in Posen two weeks after the event, declaring that he would “introduce absolute responsibility of kin… a very old custom practiced