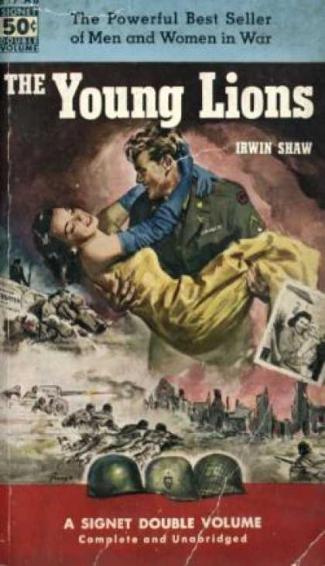

Irwin Shaw

The Young Lions

First published in 1949

CHAPTER ONE

THE town shone in the snowy twilight like a Christmas window, with the electric railway's lights tiny and festive at the foot of the white slope, among the muffled winter hills of the Tyrol. People smiled at each other broadly, skiers and natives alike, in their brilliant clothes, as they passed on the snow-draped streets, and there were wreaths on the windows and doors of the white and brown houses because this was the eve of the new and hopeful year of 1938.

Margaret Freemantle listened to her ski boots crunching in the packed snow as she walked up the hill. She smiled at the pure twilight and the sound of children singing somewhere in the village below. It had been raining in Vienna when she left that morning and people had been hurrying through the streets with that gloomy sense of being imposed upon that rain brings to a large city. The soaring hills and the clear sky and the good snow, the athletic, cosy gaiety of the village seemed like a personal gift to her because she was young and pretty and on vacation.

' Dort oben am Berge,' the children sang, 'da wettert der Wind,' their voices clear and plangent in the rare air.

'Da sitzet Maria,' Margaret sang softly to herself, 'und wieget ihr Kind.' Her German was halting and as she sang she was pleased not only with the melody and delicacy of the song, but her audacity in singing in German at all.

She was a tall, thin girl, with a slender face. She had green eyes and a spattering of what Joseph called American freckles across the bridge of her nose. Joseph was coming up on the early train the next morning, and when she thought of him she grinned.

At the door of her hotel she stopped and took one last look at the rearing, noble mountains and the winking lights. She breathed deeply of the twilight air. Then she opened the door and went in.

The main room of the small hotel was bright with holly and green leaves, and there was a sweet, rich smell of generous baking. It was a simple room, furnished in heavy oak and leather, with the spectacular, brilliant cleanliness found so often in the mountain villages, that became a definite property of the room, as real and substantial as the tables and chairs.

Mrs Langerman was walking through the room, carefully carrying a huge cut-glass punchbowl, her round, cherry face pursed with concentration. She stopped when she saw Margaret and, beaming, put the punchbowl down on a table.

'Good evening,' she said in her soft German. 'How was the skiing?'

'Wonderful,' Margaret said.

'I hope you didn't get too tired.' Mrs Langerman's eyes crinkled slyly at the corners. 'A little party here tonight. Dancing. A great many young men. It wouldn't do to be tired.'

Margaret laughed. 'I'll be able to dance. If they teach me how.'

'Oh!' Mrs Langerman put up her hands deprecatingly.

'You'll have no trouble. They dance every style. They will be delighted with you.' She peered critically at Margaret. 'Of course, you are rather thin, but the taste seems to be in that direction. The American movies, you know. Finally, only women with tuberculosis will be popular.' She grinned and picked up the punchbowl again, her flushed face pleasant and hospitable as an open fire, and started towards the kitchen. 'Beware of my son, Frederick,' she said. 'Great God, he is fond of the girls!' She chuckled and went into the kitchen.

Margaret sniffed luxuriously of the sudden strong odour of spice and butter that came in from the kitchen. She went up the steps to her room, humming.

The party started out very sedately. The older people sat rather stiffly in the corners, the young men congregated uneasily in impermanent groups, drinking gravely and sparely of the strong spiced punch. The girls, most of them large, strong-armed creatures, looked a little uncomfortable and out of place in their frilly party finery. There was an accordionist, but after playing two numbers to which nobody danced he moodily stationed himself at the punchbowl and gave way to the gramophone with American records.

Most of the guests were townspeople, farmers, merchants, relatives of the Langermans, all of them tanned a deep red-brown by the mountain sun, looking solid and somehow immortal, even in their clumsy clothes, as though no seed of illness or decay could exist in that firm mountain flesh, no premonition of death ever be admitted under that glowing skin. Most of the city people who were staying in the few rooms of the Langermans' inn had politely drunk one cup of punch and then had gone on to gayer parties in the larger hotels. Finally Margaret was the only non-villager left. She was not drinking much and she was resolved to go to bed early and get a good night's sleep, because Joseph's train was getting in at eight-thirty in the morning. She wanted to be fresh and rested when she met him. As the evening wore on, the party became gayer. Margaret danced with most of the young men, waltzes and American foxtrots. About eleven o'clock, when the room was hot and noisy and the third bowl of punch had been brought on, and the faces of the guests had lost the shy, outdoor look of dumb, simple health and taken on an indoor glitter, she started to teach Frederick how to rumba. The others stood around and watched and applauded when she had finished, and old man Langerman insisted that she dance with him. He was a round, squat old man with a bald pink head, and he perspired enormously as she tried to explain in her mediocre German, between bursts of laughter, the mystery of the delayed beat and the subtle Caribbean rhythm.

'Ah, God,' the old man said when the song ended, 'I have been wasting my life in these hills.' Margaret laughed and leaned over and kissed him. The guests, assembled on the polished floor in a close circle around them, applauded loudly, and Frederick grinned and stepped forward and put his arms up.

'Teacher,' he said, 'me again.'

They put the record on again and they made Margaret drink another cup of punch before they began. Frederick was clumsy and heavy-footed, but his arms around her felt pleasantly strong and secure in the spinning, warm dance.

The song ended and the accordionist, now freighted with a dozen glasses of punch, started up. He sang, too, as he played, and one by one the others joined him, standing around him in the firelight, their voices and the rich, swelling notes of the accordion rising in the high, beamed room. Margaret stood with Frederick's arm around her, singing softly, almost to herself, her face flushed, thinking, how kind, how warm these people are, how friendly and child-like, how good to strangers, singing the new year in, their rough outdoor voices tenderly curbed to the sweet necessities of the music.

'Roslein, Roslein, Roslein rot, Roslein auf der Heide,' they sang, old man Langerman's voice rising above the chorus, bull-like and ridiculously plaintive, and Margaret sang with them. She looked across the fireplace at the dozen singing faces. Only one person in the room remained still.

Christian Diestl was a tall, slender young man, with a solemn, abstracted face and close-cut black hair, his skin burned dark by the sun, his eyes light and almost golden with the yellow flecks you find in an animal's eyes. Margaret had seen him on the slopes, gravely teaching beginners how to ski, and had momentarily envied him the rippling, long way he had moved across the snow. Now he was standing a little behind and away from the singers, an open white shirt brilliant in contrast to his dark skin, soberly holding a glass and watching the singers with considering, remote eyes.

Margaret caught his glance. She smiled at him. 'Sing,' she said.

He smiled gravely back and lifted his glass. She saw him obediently begin to sing, although in the general