BEYOND THE GAP

Harry Turtledove

I

When the wind blew down from the north, Nidaros felt as if the Glacier had never gone away. Two thousand years before, the spired city that ruled the Raumsdalian Empire was a mammoth-hunting camp at the southeastern corner of Hevring Lake, the great accumulation of melt-water at—or rather, just beyond—the southern edge of the Glacier.

Hevring Lake was centuries gone now. Whatever had dammed its outlet to the west finally let go, and the great basin emptied in a couple of dreadful days. The scoured badlands of the Western Marches were the scarred reminders of that flood.

The Glacier had fallen back, too. New meltwater lakes farther north marked its retreating border. These days, farmers raised oats and rye and even barley in what they called Hevring Basin. No wild mammoths had been seen anywhere near Nidaros for generations. They followed the ice north. Sometimes, though, mastodons would lumber out of the forest to raid the fields.

Back when Nidaros lived by mammoth ivory and mammoth hides and rendered mammoth fat and dried mammoth flesh, no one would have imagined forests by Hevring Lake. The Glacier was strong then, and its grip on the weather even stronger. That was tundra country in those days, frozen hard forever beneath a frosty sky. So it seemed all those years ago, anyhow.

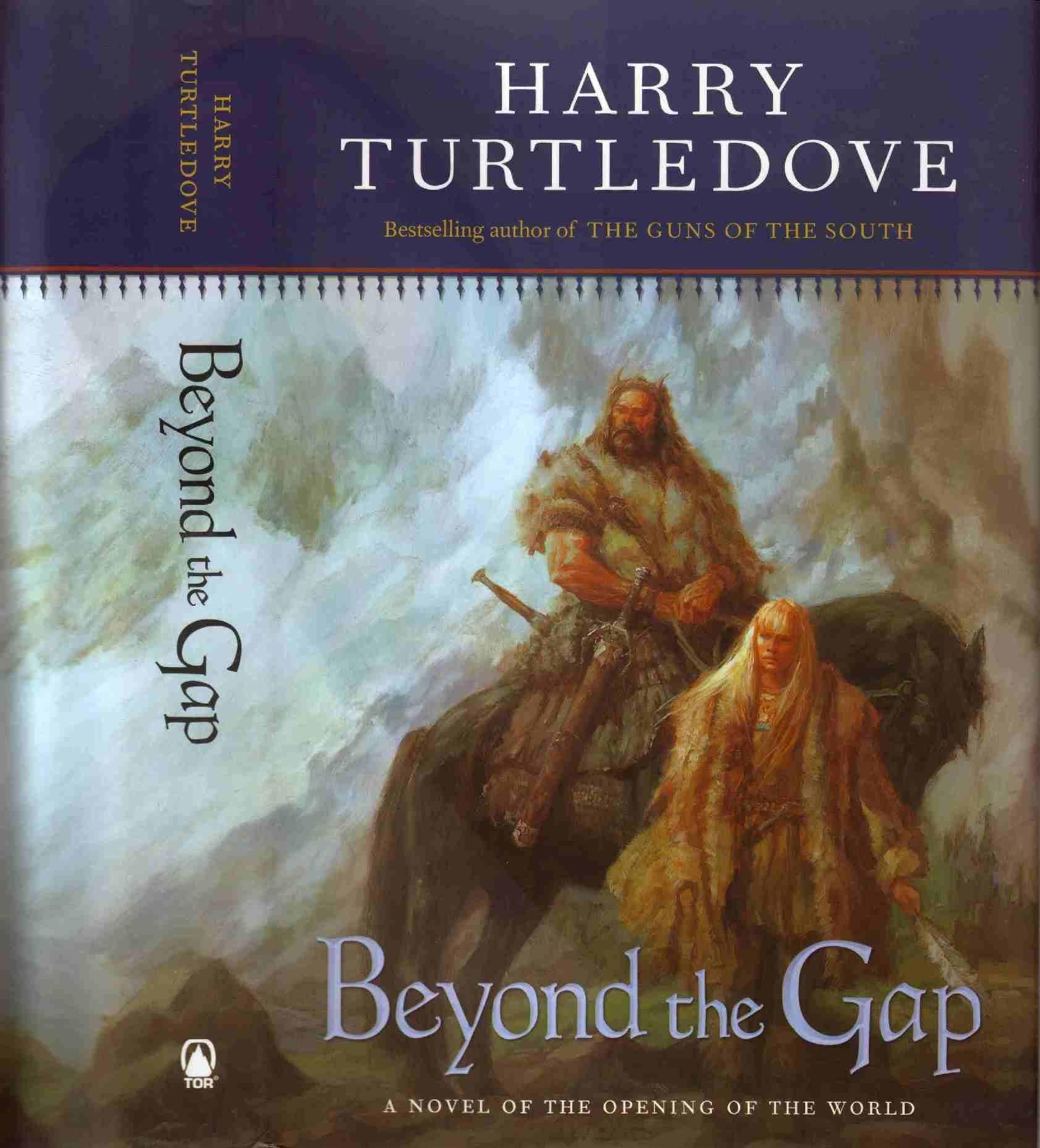

Now, as Count Hamnet Thyssen rode up toward Nidaros, he thought about how the world changed while men weren't looking. He was a big, dark, heavyset man who rode a big, dark, heavyset horse. Over his mail he wore a jacket of dire-wolf hides, closed tight against that cold north wind.

The head from a sabertooth skin topped his helm. The beast was posed so its fangs jutted forward instead of dropping down in front of his eyes.

His thoughts were as slow and ponderous as his body. Many other men would get where they were going faster than he did, whether the journey was by land or over the stormy seas of thought. But if the way got rough, or if it petered out altogether, many other men would turn back in dismay. Count Hamnet carried on ... and on, and on. Sooner or later, he got where he was going.

He muttered under his breath. Fog puffed from his mouth and his great prow of a nose. If he'd thought faster ten years ago, he would have realized sooner that his wife was betraying him. If he'd thought faster, he might even have found a way to make her not want to betray him. And if he'd moved faster in the world, her laughing lover never would have been able to lay his face open like that.

The other man was dead.

So was his love—or so he kept telling himself, anyhow. He would have taken Gudrid back. She didn't want to come. Where she'd left him secretly before, she left him openly then. And he'd never found anyone he cared about since.

He muttered again. Gudrid and Eyvind Torfinn lived in Nidaros—one more reason Hamnet stayed in his cold stone keep out on the eastern frontier as much as he could. But when the Emperor summoned, Count Hamnet came. Sigvat II was a man for whom disobedience and rebellion meant the same thing.

As Hamnet neared Nidaros' gray stone walls, he had to rein in to let a merchant caravan come out through the South Gate. Horses and mules and two-humped hairy camels were laden with the products of the north. Some carried mammoth tusks. Others bore horns cut from the carcasses of woolly rhinos. Many in the south—and not a few in the Raumsdalian Empire— believed rhinoceros horn helped a man's virility. What people believed often turned out to be true just because they believed it. Charlatans and mages were quick to take advantage of that. Which was which . . . Hamnet Thyssen shook his head. He doubted there was any firm dividing line.

Baled hides burdened other beasts. Still others bore baskets and bundles that hid their contents. A few horses hauled carts behind them. The un-greased axles squealed. The carts bumped up and down as their wheels jounced in the ruts.

Merchants rode with the animals. Some were plump and prosperous, with karakul hats and long coats of otter or marten over tunics and baggy breeches tucked into boots of buttery-soft leather or, more often, of felt. Others were accoutered more like Hamnet Thyssen—they were men ready to fight to keep what they owned.

And the caravan had a proper fighting tail of guards, too. Inside the Empire, they were probably—probably— so much swank, but beyond the borders bandit troops thrived. Some of the guards were Raumsdalians in chainmail like Hamnet's, armed with bows and slashing swords. Others were blond Bizogot mercenaries out of the north. The lancers looked as if they would rather be herding mammoths than riding horses. Even though they were many and he only one, they gave him hard stares as they rode past. Their cold blue eyes reminded him of the Glacier in whose shadow they dwelt.

He rode through the South Gate himself once the caravan came forth. A guard stepped out into the middle of the roadway to block his path. With upraised hand, the fellow said, 'Who are you, and what is your business in the capital?' He sounded like what he was—an underofficer puffed up with his own petty authority. Most men coming into Nidaros would have had to bow and scrape before him. They might have had to grease his palm before he let them pass, too. No wonder he was puffed up, then.

The count looked down his long nose at the gate guard. 'I am Hamnet Thyssen,' he said quietly. 'I have an appointment with his Majesty.'

'Oh!' The gate guard stumbled back, all but tripping over his own feet. 'P—P—Pass on, your Grace!' Petty authority punctured, he deflated like a pricked pig's bladder.

At another time—or, more likely, were he another man—that would have made Count Hamnet laugh. Here, now, he just felt sad. Without another word, he booted his horse forward and rode into smoky, smelly Nidaros.

He hadn't gone more than a few feet forward before a man sitting on horseback in front of a tavern rode out alongside him. 'Good day, Count Hamnet,' the rider said, his voice a light, musical tenor. 'God grant you long years.'

'I don't know you.' Hamnet s eyes narrowed as he surveyed the foxy-faced newcomer. The crow's-feet at their corners deepened and darkened when he did. He shook his head. 'No. Wait. Ulric Skakki, or I'm a Bizogot. Forgive me. It's been a few years.' He pulled off his right mitten and held out his hand.

Ulric Skakki had an infectious grin. As he clasped hands with Count Hamnet, he said, 'Don't worry about it, your Grace. I'm not offended. D'you think

He might have been a lot of things. Though he spoke Raumsdalian perfectly, he might well not have been a