twelve people, injuring over one thousand and causing mass panic. Technical problems, leaks and accidents plagued the cult. But the Tokyo subway attack showed what only a small amount of dangerous material could do. The Tokyo calamity resulted from 159 ounces of sarin. By contrast, in Russia, in a remote compound near the town of Shchuchye in western Siberia, there are still 1.9 million projectiles filled with 5,447 metric tons of nerve agents.13

Osama bin Laden was reportedly impressed with the Tokyo subway disaster and the chaos it generated. In 1998, Al Qaeda leaders began to launch a serious chemical and biological weapons effort, code-named Zabadi, or “curdled milk” in Arabic. Details of the effort were later revealed in documents found on a computer used by the Al Qaeda leadership in Kabul. Ayman Zawahiri, the former Cairo surgeon who that year merged his radical group, Islamic Jihad in Egypt, with Al Qaeda, noted that “the destructive power of these weapons is not less than that of nuclear weapons.”14 In 1999, Zawahiri recruited a Pakistani scientist to set up a small biological weapons laboratory in Kandahar. Later, the work was turned over to a Malaysian who knew the 9/11 hijackers and had helped them, Yazid Sufaat. He had been educated in biology and chemistry in California, and spent months at the Kandahar laboratory attempting to cultivate anthrax. George Tenet, the former CIA director, said the anthrax effort was carried out in parallel with the plot to hijack airplanes and crash them into buildings.15 He believed, he said, that bin Laden’s strongest desire was to go nuclear. At one point, the CIA frantically chased down reports that bin Laden was negotiating for the purchase of three Russian nuclear devices, although details were never found. “They understand that bombings by cars, trucks, trains, and planes will get them some headlines, to be sure,” Tenet wrote. “But if they manage to set off a mushroom cloud, they will make history… Even in the darkest days of the Cold War, we could count on the fact that the Soviets, just like us, wanted to live. Not so with terrorists.”16

It is difficult to build a working nuclear bomb, but less difficult to cultivate pathogens in a laboratory. A congressional commission concluded in 2008 that it would be hard for terrorists to weaponize and disseminate significant quantities of a biological agent in aerosol form, but it might not be so difficult to find someone to do it for them. “In other words,” the panel said, “given the high-level of know-how needed to use disease as a weapon to cause mass casualties, the United States should be less concerned that terrorists will become biologists and far more concerned that biologists will become terrorists.”17

The tools of mass casualty are more diffuse and more uncertain than ever before. Even as securing the weapons of the former Soviet Union remains unfinished business, the world we live in confronts new risks that go far beyond Biopreparat. Today one can threaten a whole society with a flask carrying pathogens created in a fermenter in a hidden garage—and without a detectable signature.

The Dead Hand of the arms race is still alive.

————— ILLUSTRATIONS —————

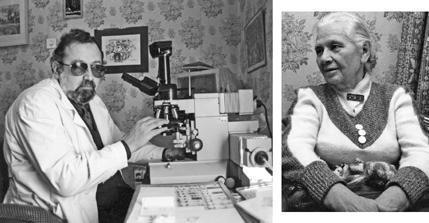

Lev Grinberg (left) and Faina Abramova, the pathologists who autopsied victims of the 1979 Sverdlovsk anthrax outbreak. [David E. Hoffman]

The Chkalovsky district, where the outbreak occurred. [David E. Hoffman]

Sergei Popov, the bright young researcher who worked on genetic engineering of pathogens, and his wife, Taissia, at Koltsovo in 1982. [Sergei Popov]

Lev Sandakhchiev, the director of Vector, who pushed to create artificial viruses for weapons. [Andy Weber]

Igor Domaradsky, the “troublemaker” at Obolensk who attempted to alter the genetic makeup of pathogens. [David E. Hoffman]

Vitaly Katayev (in eyeglasses at left), an aviation and rocket designer by profession, began in 1974 to work for the Central Committee in Moscow. In the years leading up to the Soviet collapse, he kept detailed notebooks, filled with technical information about weapons systems and key decisions. Here, he attends a May Day celebration, date unknown. [Ksenia Kostrova]

Katayev in the 1990s. [Ksenia Kostrova]

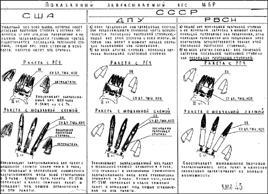

A Katayev drawing on modular missiles. [Hoover Institution Archives]

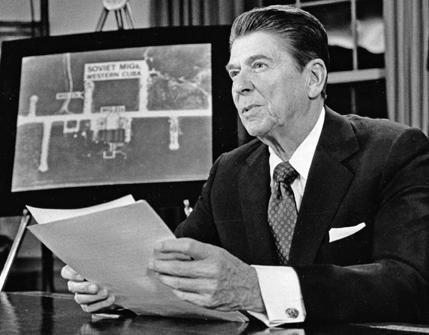

President Ronald Reagan and the Joint Chiefs of Staff discussed the concept of missile defense on February 11, 1983. The president wrote in his diary that night, “What if we tell the world, we want to protect our people, not avenge them…?” [Ronald Reagan Library]

Reagan unveiled his vision for the Strategic Defense Initiative in a televised speech on March 23, 1983. [Ray

The nuclear accident at Chernobyl in April 1986 was a turning point for Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. [Reuters]

Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev, chief of the Soviet General Staff, played a key role in Gorbachev’s drive to slow the arms race. [RIA Novosti]

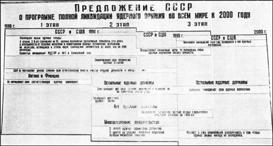

A poster outlining Gorbachev’s proposal in 1986 to eliminate all nuclear weapons by the year 2000. Akhromeyev is identified on the reverse as the main author. [Hoover Institution Archives]

At the Reykjavik summit, October 11–12, 1986, Gorbachev and Reagan came closer than any other leaders of the Cold War Period to agreements that would slash nuclear arsenals. [Ronald Reagan Library]

They parted without a deal after Reagan insisted that his cherished dream of missile defense could not be limited to research in the laboratory. [Ronald Reagan Library]

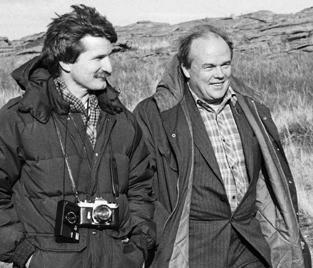

Yevgeny Velikhov (right), an open-minded physicist, helped break through the walls of Soviet military secrecy. With Thomas B. Cochran of the Natural Resources Defense Council, near the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, July 1986. [RIA Novosti]

Velikhov and Cochran arranged an unprecedented joint experiment to verify the presence of a nuclear warhead on a missile aboard the

Anatoly Chernyaev, who harbored hopes for liberal reform in the Soviet Union, became Gorbachev’s top foreign policy adviser in 1986 and remained at his side until 1991. [Photograph courtesy of Dr. Svetlana Savranskaya, National Security Archive, Washington, D.C.]

Valery Yarynich, who spent thirty years in the Soviet Strategic Rocket Forces and General Staff, helped bring to fruition the semiautomatic missile launch system known as Perimeter, a modified “Dead Hand.” [Valery