Yarynich]

Gorbachev returns to Moscow on August 21, 1991, after the failed coup attempt during which he lost control of the nuclear command system. [TASS via Agence France-Presse]

Gorbachev concludes his resignation speech on December 25, 1991. [AP Photo/Liu Heung Shing]

Secretary of State James A. Baker III closely questioned Russian President Boris Yeltsin about who controlled the nuclear weapons as the Soviet Union neared collapse. [AP Photo/Liu Heung Shing]

Vladimir Pasechnik, the director of the Institute of Ultra-Pure Biological Preparations in Leningrad, defected to Britain in 1989 and revealed the true size and scope of the Soviet biological weapons program. [Photograph courtesy of Raymond Zilinskas at the Monterey Institute]

Pasechnik’s business card.

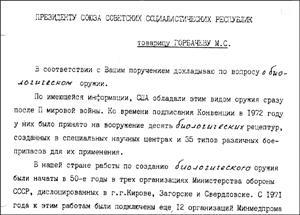

In this memo to Gorbachev about biological weapons on May 15, 1990, Politburo member Lev Zaikov wrote the word

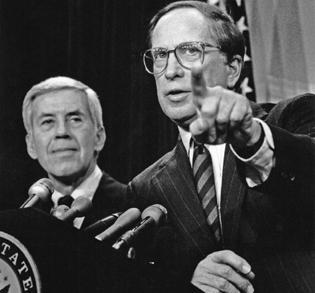

Senators Sam Nunn, Democrat of Georgia (right), and Richard Lugar, Republican of Indiana, saw the dangers of loose nuclear materials and weapons in the former Soviet Union. [Ray Lustig/

Andy Weber, a U.S. diplomat, located 1,322 pounds of highly-enriched uranium in Kazakhstan. Here, an image of the uranium, which was airlifted out in Project Sapphire. [Andy Weber]

Loading the uranium onto cargo planes to be flown to the United States. [Andy Weber]

President George H. W. Bush raised questions about biological weapons in a private talk with Gorbachev at Camp David, June 2, 1990. [George Bush Presidential Library and Museum]

Christopher Davis, the senior biological warfare specialist on the British Defense Intelligence Staff, makes a video recording during a second visit to Pasechnik’s institute in November 1992. Yeltsin promised to end the biological weapons program, but it continued nonetheless. [Christopher Davis]

Ken Alibek was chief of the anthrax factory built at Stepnogorsk, and later served as deputy director of Biopreparat, the Soviet biological weapons system. [James A. Parcell/Washington

The Stepnogorsk anthrax facility, with underground bunkers in the foreground. [Andy Weber]

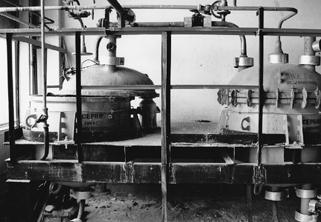

Inside the Stepnogorsk complex, machines were ready to create tons of anthrax for weapons if the Kremlin had given the order. [Andy Weber]

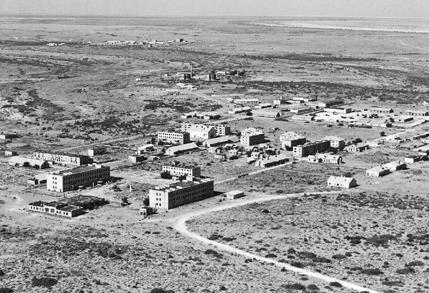

Dry, deserted Vozrozhdeniye Island as seen by Weber and his team as their helicopter approached for the first time in 1995. The island held clues to years of biological weapons testing. [Andy Weber]

Searching for buried anthrax on Vozrozhdeniye Island. [Andy Weber]

Weber, who helped uncover the secrets of the Soviet biological weapons program, found rusting cages once used to hold primates for germ warfare testing on the island. [Andy Weber]

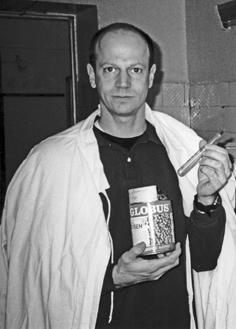

In a tin can of peas at a lightly guarded institute, Weber once found samples of plague agent. [Andy Weber]

The graves of the Sverdlovsk anthrax victims. [David E. Hoffman]

————— ACKNOWLEDGMENTS —————

I had the good fortune to be a White House correspondent for the

My insights into Reagan were drawn from several interviews as well as his eventful eight years in office, and my understanding further enriched by publication of his memoir and private diary. Mikhail Gorbachev granted two interviews for this book, and I benefited from his memoir and extensive writing and public speaking. Anatoly Chernyaev gave me his personal recollections, and his diary is one of the single most valuable accounts of the years of

Pavel Podvig shared his knowledge of Russian weapons systems and helped decipher the Katayev papers. Svetlana Savranskaya guided me with precision and patience through Cold War memoirs and documents. For additional insights and comments on the manuscript I am grateful to Bruce Blair, Christopher J. Davis, Milton Leitenberg, Thomas C. Reed, Mikhail Tsypkin, Andy Weber, Valery Yarynich and Ray Zilinskas.

I am very much in debt to Ksenia Kostrova, who assisted with the papers of her grandfather, Vitaly Katayev. After the Soviet collapse, Katayev tried to adapt, establishing a private company. He was not very successful, but he continued to dream. One of his more spectacular ideas was to use surplus intercontinental ballistic missles to assist stranded sailors, fishermen or mountain climbers. The missiles would release a rescue package tethered to a parachute. Katayev drew charts and trajectories for his ambitious plan, which he called “Project Vita.” His dream was never realized. Katayev passed away in 2001. His papers are deposited at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives, Stanford University.

Masha Lipman has long been my guiding light on Russia and offered valuable comments on the manuscript. My thanks also go to Irina Makarova, Vladimir Alexandrov and Sergei Belyakov.

At the

Lou Cannon was my partner and tutor in Reagan’s time. My thanks also go to

Robert Monroe shared far more about chemical demilitarization than I could ever absorb, and I am deeply grateful for our long conversations. For research, my thanks to Alex Remington, Josh Zumbrun, Robert Thomason and Anna Masterova. Maryanne Warrick and Abigail Crim transcribed interviews.

An important contribution came from Thomas S. Blanton and the National Security Archive in Washington, which provided key historical documents and analysis. I am also grateful to Anne Hessing Cahn for access to her