peoples. The fledgling discipline of anthropology was struggling to define its subject matter, “culture,” and to determine the boundaries between acquired and innate aspects of human behavior. In order to shed light on this question, it was essential to determine to what extent the cognitive traits of primitive people differed from those of civilized people, and the role of the expedition was to advance beyond the mostly anecdotal evidence that had been available before. As the leader of the expedition explained, “For the first time trained experimental psychologists investigated by means of adequate laboratory equipment a people in a low stage of culture under their ordinary conditions of life.” The multivolume meticulous reports that were published by Rivers and the other members in subsequent years helped to make the distinction between natural and cultural traits clearer, and the Torres Straits expedition is thus widely credited as the event that turned anthropology into a serious science.

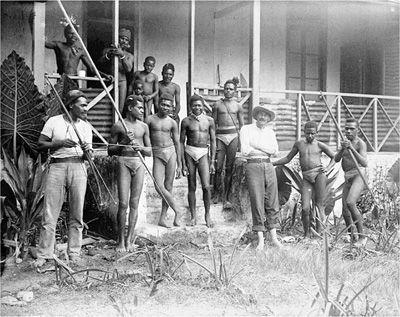

W. H. R. Rivers with friends

Rivers’s own reason for joining the expedition in 1898 was the opportunity to conduct detailed experiments on the eyesight of the natives. During the 1890s, he had been immersed in the study of vision, and so was keen to resolve the controversy over the color sense, which had not progressed much in the previous two decades. He wanted to see for himself how the color vision of the natives related to their color vocabulary and whether the capacity for appreciating differences correlated with the power of expressing those differences in language.

Rivers spent four months on the remote Murray Island, at the eastern edge of the Torres Straits, right at the northern tip of the Great Barrier Reef. With a population of about 450, the island offered a manageably small community of friendly natives who were “sufficiently civilized” to enable him to make all his observations and yet, as he put it, “were sufficiently near their primitive condition to be thoroughly interesting. There is no doubt that thirty years ago they were in a completely savage stage, absolutely untouched by civilization.”

What Rivers found in the color vocabulary of the islanders fitted well with the reports from the previous twenty years. Descriptions of color were generally vague and indefinite, and sometimes a cause of much uncertainty. The most definite names were for black, white, and red. The word for “black,”

Rivers noted that often “lively discussions were started among the natives as to the correct name of a colour.” When asked to indicate the names of certain colors, many islanders said they would need to consult wiser men. And when pressed to give an answer nevertheless, they simply tended to think of a name of particular objects. For example, when shown a yellowish green shade, one man called it “sea green” and pointed to the position of one particular large reef in view.

The vocabulary of the Murray Islanders was clearly “defective,” but what about their eyesight? Rivers examined more than two hundred of them for their ability to distinguish colors, subjecting them to rigorous tests. He used an improved and extended version of the Holmgren wool test and devised a series of experiments of his own to detect any sign of inability to perceive differences. But he did not find a single case of color blindness. Not only were the islanders able to distinguish between all primary colors, but they could also tell apart different shades of blue and of any other color. Rivers’s meticulous experiments thus demonstrated beyond any possible doubt that people can see the differences between all imaginable shades of colors and yet have no standard names in their language even for basic colors such as green or blue.

Surely, there could have been only one possible conclusion for such an acutely intelligent researcher to draw from his own findings: the differences in color vocabulary have nothing to do with biological factors. And yet there was one experience which struck Rivers so forcefully that it managed to throw him entirely off track. This was the encounter with that weirdest of all weirdnesses, a phenomenon which philologists could infer only from ancient texts but which he met face to face: people who call the sky “black.” As Rivers points out with amazement in his expedition reports, he simply could not grasp how the old men of Murray Island regarded it as quite natural to apply the term “black” (

Rivers thus concluded that Magnus was right in assuming that the natives must still suffer from a “certain degree of insensitiveness to blue (and probably green) as compared with that of Europeans.” Being such a scrupulous scientist, Rivers was not only aware of the weaknesses of his own argument but careful to air them himself. He explains that his own results proved that one cannot deduce from language what the speakers can see. He even mentions that the younger generation of speakers, who have borrowed the word

At the last hurdle, then, Rivers’s imagination simply lost its nerve and balked at the idea that “blue” is ultimately a cultural convention. He could not bring himself to concede that people who saw blue just as vividly as he did would still find it natural to regard it as a shade of black. And in all fairness, it is difficult to blame him, for even with the wealth of incontrovertible evidence at our disposal today, it is still very hard for us to muster the imagination needed to accept that blue and black seem separate colors just because of the cultural conventions we were reared on. Our deepest instincts and guttest of feelings yell at us that blue and black are

The first experiment is an exercise in counterfactual history. Let’s imagine how the color-sense debate might have unfolded had it been conducted not in England and Germany but in Russia. Imagine that a nineteenth-century Russian anthropologist, Yuri Magnovievitch Gladonov, goes on an expedition to the remote British Isles off the northern coast of Europe, where he spends a few months with the reclusive natives and conducts detailed psychological tests on their physical and mental skills. On his return, he surprises the Royal Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg with a sensational report. It turns out that the natives of Britain show the most curious confusions in their color terminology in the