Asa Larsson

Until Thy Wrath Be Past

The fourth book in the Rebecka Martinsson series, 2011

Translated from the Swedish by Laurie Thompson

First published in Swedish as

Copyright © Asa Larsson, 2008

I remember how we died. I remember, and I know. That’s the way it is now. I know about certain things even though I wasn’t actually present when they happened. But I don’t know everything. Far from it. There are no rules. Take people, for instance. Sometimes they are open rooms that I can walk into. Sometimes they are closed. Time doesn’t exist. It’s as if it’s been whisked into nothingness.

Winter came without snow. The rivers and lakes were frozen as early as September, but still the snow didn’t come.

It was October 9. The air was cold. The sky very blue. One of those days you’d like to pour into a glass and drink.

I was seventeen. If I were still alive, I’d be eighteen now. Simon was nearly nineteen. He let me drive even though I didn’t have a licence. The forest track was full of potholes. I liked driving. Laughed at every bump. Sand and gravel clattered against the chassis.

“Sorry, Bettan,” Simon said to the car, stroking the cover of the glovebox.

We had no idea that we were going to die. That I would be screaming, my mouth full of water. That we only had five hours left.

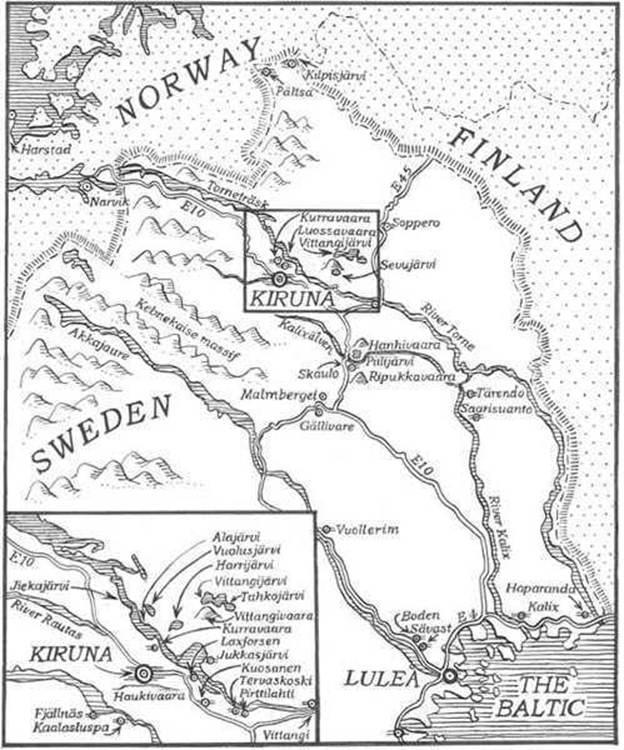

The track petered out at Sevujarvi. We unpacked the car. I kept stopping to look round. Everything was divinely beautiful. I lifted my arms towards the sky, screwed up my eyes to look at the sun, a burning white sphere, watched a wisp of cloud scudding along high above us. The mountains embodied permanence and times immemorial.

“What are you doing?” Simon said.

I was still gazing at the sky, arms raised, when I said, “Nearly all religions have something like this. Looking up, reaching up with your hands. I understand why. It makes you feel good. Try it.”

I took a deep breath, then let the air out to form a big white cloud.

Simon smiled and shook his head. Heaved his weighty rucksack up onto a rock and wriggled into the harness. He looked at me.

Oh, I remember how he looked at me. As if he couldn’t believe his luck. And it’s true. I wasn’t just any old bit of skirt.

He liked to explore me. Count all my birthmarks. Or tap his fingernail on my teeth as I smiled, ticking off all the peaks of the Kebnekaise massif: “South Peak, North Peak, Dragon’s Back, Kebnepakte, Kaskasapakte, Kaskasatjakko, Tuolpagorni.”

“Upper right lateral incisor – signs of decay; upper right central – sound; upper left central – distal filling,” I’d reply.

The rucksacks containing our diving equipment weighed a ton.

We walked up to Lake Vittangijarvi. It took us three and a half hours. We urged each other on, noticing how the frozen ground made walking easier. We sweated a lot, stopped occasionally to have some water, and once to drink coffee from our thermos flask and eat a couple of sandwiches.

Frozen puddles and frostbitten moss crackled beneath our feet.

Alanen Vittangivaara loomed on our left.

“There’s an old Sami sacrificial site up there,” Simon said, pointing. “Uhrilaki.”

That was a side of him I loved. He knew about that sort of thing.

We finally got there. Placing our rucksacks carefully on the slope, we stood in silence for a while, gazing out over the lake. The ice resembled a thick black pane of glass over the water. Trapped bubbles traced patterns like broken pearl necklaces. The cracks resembled crumpled tissue paper.

Frost had nipped at every blade of grass, every twig, making them brittle and crispy white. Sprays of lingonberry and stunted juniper bushes were a dull shade of wintry green. Dwarf birches and blueberry sprigs had been squeezed into shades of blood and violet. And everything was coated with rime. An aura of ice.

It was uncannily quiet.

Simon became withdrawn and thoughtful, as he usually did. He’s the type who can tell time to stand still. Or was. He was that kind of person.

But I’ve never been able to keep quiet for long. I just had to start shouting. All that beauty – it was enough to make you burst.