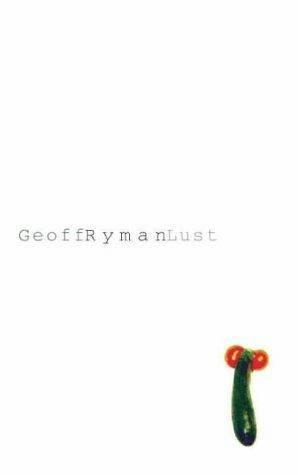

Geoff Ryman

Lust Or No Harm Done

para o meu Txay

Um livro dedicado a ti deveria ser intitulado

A text produced from the Book of Genesis using a method invented by Jean Lescure in which each noun is replaced with the seventh noun following it in a dictionary.

As reported in

Acknowledgement:

The experiment with chicks described in this novel is loosely based on a real experiment described in

Part I. So how does it start?

Michael was happy. It was the first day of his research project. His team waited for him outside the gates of the lab, in the March chill. Ebru, Emilio and Hugh all smiled when they saw him.

It was a new lab, in rooms within arches under a railway. Michael had the keys, leading his team into one beautiful new room after another. They moved their desks and wired up their computers. They arranged staplers, pens and envelopes in drawers, determined that everything would stay tidy.

Ebru had brought flowers and a traditional Turkish shepherd's cloak to hang on the wall. She was one of Michael's students, doing a doctorate of her own, and had been hired to help administer the project. Ebru had bet Emilio a bottle of champagne that his new network would crash. Instead, the network came triumphantly to life, and they exchanged chiding e-mails, and raised glasses of champagne to the start of their brave new project.

'To continued funding,' toasted Michael. They all laughed.

The first shipment of eggs arrived in a box marked fragile computers. This was to fox the animal rights activists. The eggs were packed in grey foam like recording equipment. Ebru and Michael laid them out in the darkroom, on straw, to hatch. Everything was in place.

'This is going to work,' said Michael.

In the evening Michael went to his gym. He saw Tony. Tony was a trainer and Michael had a crush on him. Tony was tall and sleek and so innocent in his manner that Michael's nickname for him was the Cherub. Tony had a radiant announcement to make.

'I decided to take the plunge,' Tony said. 'Jacqui and I are going to get married.' He had the eyes of a happy schoolboy.

'Aw, that's fantastic. Well done!' said Michael and they did an old-fashioned hand slap. Tony's hair was cut short and dressed in spikes. Everything about him took Michael back to his youth. Tony talked a little bit about how he had realized he didn't want anyone else. 'It'll mean moving up north, but hey, she's worth it.'

That's what I want, thought Michael. I want a beautiful love.

Inspired in his heart and in his belly, Michael decided to visit the sauna in Alaska Street.

The smell of the place – hot pinewood, steam and bodies – produced an undertow of excitement as if something were pulling insistently downwards on his stomach. Naked men circulated in the steam in early evening.

Stripped of his glasses and lab coat, Michael was tall and athletic. A young Sikh with his hair tied at the top of his head in a bun saw Michael and did an almost comic double take. He was hairy and running slightly to fat, but the face, Michael suddenly saw, was smooth as marble. This was a young man with a fatherly body.

Michael followed the Sikh into the steam room with its benches. The Sikh looked at him with a teasing smile. They moved towards each other.

Michael didn't trust kissing. He knew people often brushed their teeth before cruising. Brushing teeth always produced blood; blood carried the virus. When the boy leaned towards him, Michael turned his head away and pressed his cheek against his. Michael gave him quick, dishonest pecks on the lips, pretending to be romantic and playful instead of merely safe.

Even this was enough for the young man. They sat down and Michael leaned back on the bench as they embraced. Briefly they made a shape together like a poster for

Michael's cock stayed dead. All the young man's ministrations only made it worse. It retreated further, back up and away. Not again, thought Michael, not again. It always happened, and it was always worse than Michael remembered. It was always worse with someone he liked. Most especially it happened with people he liked. The Sikh stopped, and looked up. He turned down his mouth in a show of childish disappointment.

Michael asked, 'Are you too hot? Would you like something to drink?'

It was a way of saving face.

On the mezzanine, there were free drinks in the fridge and smelly beanbags on the floor. Michael poured them each a glass of spring water. Perched on a beanbag like a Buddha, the boy shook down his long glossy hair and began to retie it. Michael wanted to take him home and watch him wind it in his turban.

Michael passed him the water and the young man gave him a sharp little smile of thanks. When Michael lay down next to him, the Sikh stayed seated upright. In his heart, Michael knew what that meant, but yearning and hope persisted.

The young man talked politely. He was a medical doctor, a specialist in tropical diseases. He had been working in Africa and was back home to see his family. His name was Deep.

Michael asked him: did he work for Medecins sans Frontieres?

'No, I don't like those organizations. They are too Western. They go there thinking they will show the natives how to do it. But, you know, they have no experience of infectious disease. I apply for the same jobs as the local doctors. I learn more that way.'

He was pleased to talk about his time there. The lack of roads, the digging of wells. Suddenly Deep lay back and let Michael rest his head on his fatherly bosom. Deep's breath smelled of liquorice. 'You know, I was working in a hospital in Malawi, by a lake. I was sitting out by myself drinking a beer. And I could see the animals come down to drink. The deer and the lions. And I could watch the deer as they kept watch. They kept flicking their ears. There was a moon on the lake.'

I'd go there with you, thought Michael. For just a moment he glimpsed another life. He was by that lake with Deep and they were together and Michael was doing… what? Michael was binding an antelope's broken shin.