passports to prove that we were British; marriage certificates to enable us to buy the house in our joint names; divorce certificates to prove that our marriage certificates were valid; proof that we had an address in England. (Our driver's licenses, plainly addressed, were judged to be insufficient; did we have more formal evidence of where we were living, like an old electricity bill?) Back and forth between France and England the pieces of paper went-every scrap of information except blood type and fingerprints-until the local lawyer had our lives contained in a dossier. The transaction could then proceed.

We made allowances for the system because we were foreigners buying a tiny part of France, and national security clearly had to be safeguarded. Less important business would doubtless be quicker and less demanding of paperwork. We went to buy a car.

It was the standard Citroen

The salesman looked at our driver's licenses, valid throughout the countries of the Common Market until well past the year 2000. With an expression of infinite regret, he shook his head and looked up.

We produced our secret weapons: two passports.

We rummaged around in our papers. What could he want? Our marriage certificate? An old English electricity bill? We gave up, and asked him what else, apart from money, was needed to buy a car.

'You have an address in France?'

We gave it to him, and he noted it down on the sales form with great care, checking from time to time to make sure that the third carbon copy was legible.

'You have proof that this is your address? A telephone bill? An electricity bill?'

We explained that we hadn't yet received any bills because we had only just moved in. He explained that an address was necessary for the

Fortunately, his salesman's instincts overcame his relish for a bureaucratic impasse, and he leaned forward with a solution: If we would provide him with the deed of sale of our house, the whole affair could be brought to a swift and satisfactory conclusion, and we could have the car. The deed of sale was in the lawyer's office, fifteen miles away. We went to get it, and placed it triumphantly on his desk, together with a check. Now could we have the car?

It made us mildly paranoid, and for weeks we never left home without photocopies of the family archives, waving passports and birth certificates at everyone from the checkout girl at the supermarket to the old man who loaded the wine into the car at the cooperative. The documents were always regarded with interest, because documents are holy things here and deserve respect, but we were often asked why we carried them around. Was this the way one was obliged to live in England? What a strange and tiresome country it must be. The only short answer to that was a shrug. We practiced shrugging.

The cold lasted until the final days of January, and then turned perceptibly warmer. We anticipated spring, and I was anxious to hear an expert forecast. I decided to consult the sage of the forest.

Massot tugged reflectively at his mustache. There were signs, he said. Rats can sense the coming of warmer weather before any of those complicated satellites, and the rats in his roof had been unusually active these past few days. In fact, they had kept him awake one night and he had loosed off a couple of shots into the ceiling to quieten them down.

February

THE FRONT PAGE of our newspaper,

This traditional mixture was put aside, one morning in early February, for a lead story which had nothing to do with sport, crime, or politics: PROVENCE UNDER BLANKET OF SNOW! shouted the headline with an undercurrent of glee at the promise of the follow-up stories which would undoubtedly result from Nature's unseasonable behavior. There would be mothers and babies miraculously alive after a night in a snowbound car, old men escaping hypothermia by inches thanks to the intervention of public-spirited and alert neighbors, climbers plucked from the side of Mont Ventoux by helicopter, postmen battling against all odds to deliver electricity bills, village elders harking back to previous catastrophes-there were days of material ahead, and the writer of that first story could almost be seen rubbing his hands in anticipation as he paused between sentences to look for some more exclamation marks.

Two photographs accompanied the festive text. One was of a line of white, feathery umbrellas-the snow- draped palm trees along the Promenade des Anglais in Nice. The other showed a muffled figure in Marseilles dragging a mobile radiator on its wheels through the snow at the end of a rope, like a man taking an angular and obstinate dog for a walk. There were no pictures of the countryside under snow because the countryside was cut off; the nearest snowplow was north of Lyon, three hundred kilometers away, and to a Provencal motorist-even an intrepid journalist-brought up on the sure grip of baking tarmac, the horror of waltzing on ice was best avoided by staying home or holing up in the nearest bar. After all, it wouldn't be for long. This was an aberration, a short- lived climatic hiccup, an excuse for a second

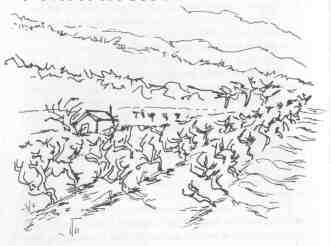

Our valley had been quiet during the cold days of January, but now the snow had added an extra layer of silence, as though the entire area had been soundproofed. We had the Luberon to ourselves, eerie and beautiful, mile after mile of white icing marked only by occasional squirrel and rabbit tracks crossing the footpaths in straight and purposeful lines. There were no human footprints except ours. The hunters, so evident in warmer weather with their weaponry and their arsenals of salami, baguettes, beer, Gauloises, and all the other necessities for a day out braving nature in the raw, had stayed in their burrows. The sounds we mistook for gunshots were branches snapping under the weight of great swags of snow. Otherwise it was so still that, as Massot observed later, you could have heard a mouse fart.

Closer to home, the drive had turned into a miniature mountainscape where wind had drifted the snow into a range of knee-deep mounds, and the only way out was on foot. Buying a loaf of bread became an expedition lasting nearly two hours-into Menerbes and back without seeing a single moving vehicle, the white humps of parked cars standing as patiently as sheep by the side of the hill leading up to the village. The Christmas-card weather had infected the inhabitants, who were greatly amused by their own efforts to negotiate the steep and treacherous streets, either teetering precariously forward from the waist or leaning even more precariously backward, placing their feet with the awkward deliberation of intoxicated roller-skaters. The municipal