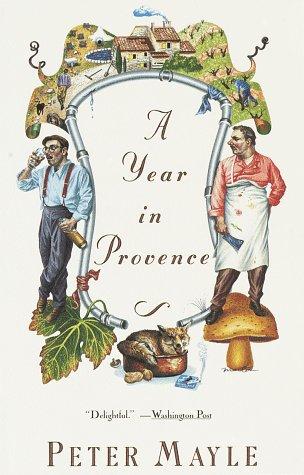

Peter Mayle

A Year In Provence

January

THE YEAR BEGAN with lunch.

We have always found that New Year's Eve, with its eleventh-hour excesses and doomed resolutions, is a dismal occasion for all the forced jollity and midnight toasts and kisses. And so, when we heard that over in the village of Lacoste, a few miles away, the proprietor of Le Simiane was offering a six-course lunch with pink champagne to his amiable clientele, it seemed like a much more cheerful way to start the next twelve months.

By 12:30 the little stone-walled restaurant was full. There were some serious stomachs to be seen- entire families with the

The final

We had been here often before as tourists, desperate for our annual ration of two or three weeks of true heat and sharp light. Always when we left, with peeling noses and regret, we promised ourselves that one day we would live here. We had talked about it during the long gray winters and the damp green summers, looked with an addict's longing at photographs of village markets and vineyards, dreamed of being woken up by the sun slanting through the bedroom window. And now, somewhat to our surprise, we had done it. We had committed ourselves. We had bought a house, taken French lessons, said our good-byes, shipped over our two dogs, and become foreigners.

In the end, it had happened quickly-almost impulsively-because of the house. We saw it one afternoon and had mentally moved in by dinner.

It was set above the country road that runs between the two medieval hill villages of Menerbes and Bonnieux, at the end of a dirt track through cherry trees and vines. It was a

It was also immune, as much as any house could be, from the creeping horrors of property development. The French have a weakness for erecting

The Luberon Mountains rise up immediately behind the house to a high point of nearly 3,500 feet and run in deep folds for about forty miles from west to east. Cedars and pines and scrub oak keep them perpetually green and provide cover for boar, rabbits, and game birds. Wild flowers, thyme, lavender, and mushrooms grow between the rocks and under the trees, and from the summit on a clear day the view is of the Basses-Alpes on one side and the Mediterranean on the other. For most of the year, it is possible to walk for eight or nine hours without seeing a car or a human being. It is a 247,000-acre extension of the back garden, a paradise for the dogs and a permanent barricade against assault from the rear by unforeseen neighbors.

Neighbors, we have found, take on an importance in the country that they don't begin to have in cities. You can live for years in an apartment in London or New York and barely speak to the people who live six inches away from you on the other side of a wall. In the country, separated from the next house though you may be by hundreds of yards, your neighbors are part of your life, and you are part of theirs. If you happen to be foreign and therefore slightly exotic, you are inspected with more than usual interest. And if, in addition, you inherit a long- standing and delicate agricultural arrangement, you are quickly made aware that your attitudes and decisions have a direct effect on another family's well-being.

We had been introduced to our new neighbors by the couple from whom we bought the house, over a five- hour dinner marked by a tremendous goodwill on all sides and an almost total lack of comprehension on our part. The language spoken was French, but it was not the French we had studied in textbooks and heard on cassettes; it was a rich, soupy patois, emanating from somewhere at the back of the throat and passing through a scrambling process in the nasal passages before coming out as speech. Half-familiar sounds could be dimly recognized as words through the swirls and eddies of Provencal:

Fortunately for us, the good humor and niceness of our neighbors were apparent even if what they were saying was a mystery. Henriette was a brown, pretty woman with a permanent smile and a sprinter's enthusiasm for reaching the finish line of each sentence in record time. Her husband, Faustin-or Faustang, as we thought his name was spelled for many weeks-was large and gentle, unhurried in his movements and relatively slow with his words. He had been born in the valley, he had spent his life in the valley, and he would die in the valley. His father, Pepe Andre who lived next to him, had shot his last boar at the age of eighty and had given up hunting to take up the bicycle. Twice a week he would pedal to the village for his groceries and his gossip. They seemed to be a contented family.

They had, however, a concern about us, not only as neighbors but as prospective partners, and, through the fumes of

Most of the six acres of land we had bought with the house was planted with vines, and these had been looked after for years under the traditional system of