de Vos, A. (1958) “Summer Observations on Moose Behavior in Ontario.” Journal of Mammalogy 39:128–39.

*Dodds, D. G. (1958) “Observations of Pre-Rutting Behavior in Newfoundland Moose.” Journal of Mammalogy 39:412–16.

*Geist, V (1963) “On the Behavior of the North American Moose (Alces alces andersoni Peterson 1950), in British Columbia.” Behavior 20:377–416.

Houston, D. B. (1974) “Aspects of the Social Organization of Moose.” In V. Geist and F. Walther, eds., The Behavior of Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 2, pp. 690–96. IUCN Publication no. 24. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Kojola, I. (1991) “Influence of Age on the Reproductive Effort of Male Reindeer.” Journal of Mammalogy 72:208–10.

*Lent, P. C. (1974) “A Review of Rutting Behavior in Moose.” Naturaliste canadien 101:307–23.

———(1966) “Calving and Related Social Behavior in the Barren-Ground Caribou.” Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 23:701–56.

Miquelle, D. G., J. M. Peek, and V. Van Ballenberghe (1992) “Sexual Segregation in Alaskan Moose.” Widlife Monographs 122:1–57.

*Murie, O. J. (1928) “Abnormal Growth of Moose Antlers.” Journal of Mammalogy 9:65.

*Pruitt, W. O., Jr. (1966) “The Function of the Brow-Tine in Caribou Antlers.” Arctic 19:111-13.

———(1960) “Behavior of the Barren-Ground Caribou.” Biological Papers of the University of Alaska 3:1–44.

*Reimers, E. (1993) “Antlerless Females Among Reindeer and Caribou.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 71:1319–25.

Skogland, T. (1989) Comparative Social Organization of Wild Reindeer in Relation to Food, Mates, and Predator Avoidance. Advances in Ethology no. 29. Berlin and Hamburg: Paul Parey Scientific Publishers.

Van Ballenberghe, V, and D. G. Miquelle (1993) “Mating in Moose: Timing, Behavior, and Male Access Patterns.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 71:1687–90.

*Wishart, W. D. (1990) “Velvet-Antlered Female Moose (Alces alces).” Alces 26:64–65.

GIRAFFES, ANTELOPES, AND GAZELLES

IDENTIFICATION: The tallest mammal (up to 19 feet), with a sloping back, enormously long neck, bony, knobbed “horns” in both sexes, and the familiar reddish brown spotted patterning. DISTAIBUTION: Sub- Saharan Africa. HABITAT: Savanna. STUDY AREAS: Tsavo East and Nairobi National Parks, Kenya; Serengeti, Arusha, and Tarangire National Parks, Tanzania; eastern Transvaal, South Africa; subspecies G.c. tippel-skirchi, the Masai Giraffe, and G.c. giralla.

Social Organization

Female Giraffes tend to congregate in groups of up to 15 individuals, including their calves and perhaps a few younger males. Males generally associate in all-male “bachelor” groups, but tend to become solitary as they get older. The mating system is polygamous: mostly a few older males mate with more than one female, but take no part in raising their offspring.

Description

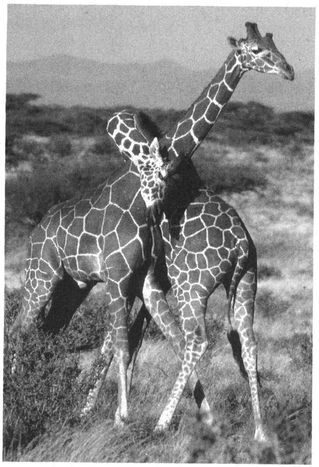

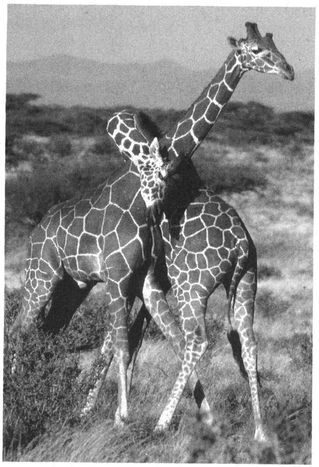

Behavioral Expression: Male Giraffes have a unique “courtship” or affectionate activity called NECKING, which is often associated with homosexual mounting. When necking, two males stand side by side, usually facing in opposite directions, while they gently rub their necks on each other’s body, head, neck, loins, and thighs, sometimes for as long as an hour. Necking sessions are usually initiated with one male assuming a formal posture with his neck held rigid and upright. One male may also affectionately lick the other’s back or sniff his genitals during necking. Necking Giraffes also sometimes swing their necks at each other in what has been described as a “stately dance” or a form of play-fighting (although they rarely hit, and virtually never injure, each other). Necking usually leads to sexual arousal: one or both males develop erections, and occasionally one might exhibit a curling of the lip similar to the FLEHMEN response seen in heterosexual courtships (associated with sexual arousal and testing sexual “readiness”). Sometimes after necking for 15 minutes or so, one male suddenly stops and “freezes” with his neck stretched forward, which is thought to indicate intense sexual excitement approaching orgasm. Males also commonly mount each other with erect penises during or following bouts of necking and probably reach orgasm (sometimes liquid—presumably semen—can be seen streaming from their penises). At times, groups of four or five males will gather to neck and mount each other, and males may mount several individuals in quick succession or the same male as many as three times in a row. Females also occasionally mount each other, but they do not participate in necking.

Two male Giraffes engaging in “necking” behavior

Frequency: Homosexual activity is common in Giraffes and in many cases is actually more frequent than heterosexual behavior (which may be quite rare): in one study area, mountings between males accounted for 94 percent of all observed sexual activity. Anywhere from a third to three-quarters of all courtship sessions are homosexual (i.e. they involve necking between males), and at any given time, about 5 percent of all males are participating in necking. Among females, less than 1 percent of interactions involving body contact consist of homosexual mounting.

Orientation: Homosexual activity is characteristic of younger adult males, who may constitute more than 80 percent of the male population. As they get older, males participate less in homosexual courtship and mounting and more in heterosexual activity. Among younger males, it is likely that all of their mounting behavior is homosexual, although a small percentage also court (but do not mount) females. Males participating in homosexual mounting and necking frequently disregard any females present in the herd, perhaps indicating a “preference” for same-sex activity.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Only a relatively small percentage of adult Giraffes breed: in some populations, less than a quarter of the females reproduce in any year, while usually only one or two males actually mate with females. A number of factors contribute to this infrequency of breeding: pregnancies last 15 months, and there is a minimum of 20 months between calves. Males are unable to compete successfully for matings until they are at least eight years old, even though they mature sexually at under four years. And as mentioned above, actual copulations can be remarkably rare—in one population, only a single heterosexual mating was observed during more than 3,200 hours of detailed observation over an entire year. In some areas, it also appears that a small class of old, postreproductive males are generally solitary and do not court or mate with females. Giraffes engage in a few forms of nonprocreative heterosexual activity as well: younger females in heat occasionally mount male calves, while calves sometimes mount their mothers. As in most polygamous animals, males do not participate in calf-raising. Females, however, often leave their young in nursery groups or CALVING POOLS containing as many as nine other calves, attended by one or more of the other mothers. This “day-care” arrangement allows a female to feed on her own without having to constantly look after her calf.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss