• Interfaces with the most popular bomb warheads (Mk 83, Mk 84, and BLU-109/B).

• In-flight targeting and delivery, independent of weather and/or lighting conditions.

• Good standoff range (more than 8.5nm./15.5km. downrange and 2 nm./3.7 km. cross-range) and the ability to target more than one target /weapon at a time.

While this may sound like quite a lot to ask of a munition which has yet to even undergo its first engineering drop tests, the principles behind the JDAM system are both sound and mature. GPS/inertial guidance systems proved their worth during Desert Storm, and are more than capable of doing the job with JDAM. And as we have mentioned earlier, JDAM may not even be the first GPS-aided bombs, if Northrop and Rockwell have their way.

As currently planned, there will be five separate versions of the Phase I JDAM family. They include:

Each JDAM kit will be composed of an aerodynamic nose cap which is bolted onto the nose fitting of the bomb warhead, and a guidance section/fin group which is bolted onto the rear. Contained in the fin group at the rear of the bomb will probably be a small GPS/receiver antenna system to pull in the signals from the satellites and feed navigational updates to the inertial guidance /steering system. Other than that, all mounting, fusing, and arming hardware will be identical to other PGMs.

As for their employment, all the pilot of an attacking aircraft will require is a known target location (preferably one with coordinates correlated with GPS accuracy), and a weapons delivery system capable of plotting a ballistic course to the target. While an onboard GPS receiver would be of great help, it is not necessary to the delivery of the JDAM munition. Once the bomb has been fed the target position and is launched, it will do its best, within the limits of the energy imparted by the launch aircraft, to head for the three-dimensional position of the target. Once there, it acts like any other bomb and explodes — in short, a very simple, yet very elegant solution to getting PGMs on target. Early tests of JDAM hardware on test benches are already showing accuracies in the 3.3- to-9.8 foot / 1-to-3 meter range, without any other added guidance systems. This is the future of PGMs, where the attacking aircraft only has to know the position of a target to kill it.

AIR-TO-GROUND MISSILES

Ever since young David used a stone projected by a sling to slay the giant warrior Goliath from a safe distance, warriors have dreamed of weapons that allow them to attack from a distance that makes counterattack impossible. Standoff. This has been the idea behind almost every weapon innovation — from the catapult, to the cannon, to the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). During the 1940s and 1950s, a generation of designers and engineers worked to create long-range weapons. For Nazi Germany, there was the Fi-103 flying bomb, known better as

None of these early standoff weapons had any real precision; the mission was simple delivery of a large warhead to the general target area. True stand-off precision weapons had to wait for the development of electronic seeker technology in the 1960s. Earlier, we saw how the first precision seekers were developed for guided bombs like the Paveway-series LGBs, and the GBU-15, so that they could destroy point targets like bridges and bunkers. A precision-guided missile combines seeker technology with a propulsion system to extend its range.

As we head towards the 21st century, the USAF has a growing array of standoff air-to-ground missiles (known by their AGM designator) for use against heavily defended targets. These weapons are highly specialized for the targets they are designed to destroy. They also tend to be expensive, with typical unit prices in the six-figure range. However, when compared to the cost of a lost aircraft ($20 million and up) and the human and political costs of lost or imprisoned aircrews, these weapons can be very cheap indeed.

AGM-65 Maverick

We'll start our look at what pilots like to call 'gopher zappers' with the oldest air-to-ground missile in the USAF inventory, the AGM-65 Maverick. Maverick draws its roots from two different programs, the early electro- optical guided bomb projects and the Martin AGM-12 Bullpup (originally designated the ASM-N-7 Bullpup A by its first user, the U.S. Navy). Bullpup was an attempt to extend the range of the basic High Velocity Artillery Rocket (HVAR) used by U.S. aircraft since World War II. Bullpup provided a large warhead (250 lb./113.6 kg.), a rocket motor, and a guidance package to keep the whole thing on course. From a safe distance (8.8 nm./16.1 km.) one Bullpup could kill targets that previously required many aircraft with lots of bombs or unguided rockets. Guidance was provided by a command line-of-sight system, which sent the missile flying down a radio 'pencil beam.' All the operator had to do was keep the nose of his aircraft on the target, and the missile would fly down the beam and impact the target. When it came into service in 1959, it was a wonder to its operators, who saw it as something of a 'silver bullet.' The problem was that the AGM-12's guidance system compelled the combat aircrew to fly straight and level toward the target during the missile's entire time of flight.

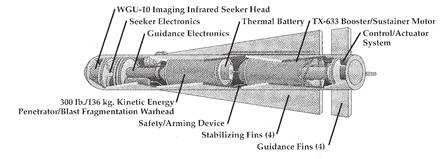

In 1965, the Air Force began a program to develop a successor to the Bullpup. After a three-year competition between Hughes Missile Systems and Rockwell, Hughes won the contract in 1968. The development of the new missile proceeded smoothly, and it came into service in 1972 as the AGM-65A Maverick. Aircrews who saw the new weapon thought it looked like the big brother of the AIM-4/GAR-8 Falcon air-to-air missile, which was no surprise, since Hughes had also designed and built the Falcon. The Maverick shows its Hughes family roots, having the same general configuration as the Navy's much larger AIM-54 Phoenix air-to-air missile. Externally, the Maverick has changed very little in the last two decades that it has been in service. The airframe is 12in./30.5cm. in diameter and 98in./ 248.9 cm. long. Wingspan of the cruciform guidance and stabilization fins is 28.3 in./71.9 cm. These dimensions make it the smallest, most compact AGM in the USAF inventory, one of the major reasons for its popularity.

It's what's inside that counts, and that is what differentiates the various versions of the AGM-65. The — A model Maverick, which first entered combat service during the Christmas bombing of North Vietnam in 1972, is an E/O guided weapon, much like the GBU-8 or GBU-15. Its main characteristics were a 5deg field-of-view (FOV) DSU-27/B seeker, with a huge 125 lb./56.8 kg. shaped charge warhead (that's really big for one of these!) that could cut through virtually any armor or bunker in existence. Weighing in at 463 lb./ 210 kg., it was powered by a Thiokol SR 109-TC-1/TX-481 two-stage (boost and sustainer) solid propellant rocket motor, giving it a maximum range of roughly 13.2 nm./24.1 km. To fire it, the operator (the backseater of an F-4D Phantom II fighter) selected a missile and powered it up. Once the missile was 'warm' with the onboard gyros running, the operator would view the picture from the missile's onboard black-and-white TV seeker and select a target with a set of crosshairs. Like other early E/O weapons, the — A model Maverick tracked its targets by looking for zones of contrast between light and dark areas. For example, a tank or bunker might appear as a dark shape on a lighter background, and this was what the TV seeker of the early Maverick was designed to track. Once the operator had the target in the crosshairs, he would press a switch to lock on the target, and the seeker would begin to track the target, regardless of the