ill-fated brig. The location is exactly where the ship’s log placed the efforts to save the stranded vessel, off what is still known as San Island inside the Columbia’s mouth. And the remains on the bottom show a determined salvage effort, from the open cargo ports to the hacked-off rigging fittings. But the real indicator, in the end, is that single, crudely hacked hole in the side.

On return dives to

CHAPTER TWO

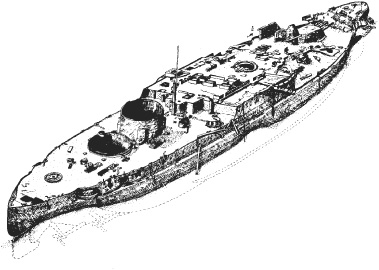

PEARL HARBOR

Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy — the United States was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan… The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian Islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. Very many American lives have been lost… Always we will remember the character of the onslaught against us. No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory.” The indignant and stirring words of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as he addressed Congress on December 8, 1941, ring through my mind as my plane crosses the United States. I’m on the way to Pearl Harbor to join a long-standing National Park Service survey of USS

Being an archeologist thoroughly at home in the mid-nineteenth century, I am surprised by the realization that I’ve worked on more World War II wrecks than any other type of ship. That includes a decade of work for the National Park Service, studying and documenting World War II fortifications and battle sites. Recently, I have been posted to Washington, D.C., as the first maritime historian of the National Park Service, to head up a new program to inventory and assess the nation’s maritime heritage, and the work included dozens of visits to preserved warships and museums.

I’ve already studied one shipwreck, the Civil War ironclad USS

Most of the initial survey work on

Standing on the narrow concrete dock while a group of tourists slowly files into the

Around me is a group of other divers drawn from the ranks of the National Park Service and the U.S. Navy, all of us preparing our gear and suiting up to jump into the dark green waters of the harbor. The water is too warm for a wetsuit, but bare skin is no protection against barnacles and rusted steel, so I pull on a pair of Park Service dark green coveralls before strapping on my weight belt, tanks and gear.

After reading dozens of books and poring over files and interviews with men who fought here on that tragic day, I’m ready to explore a ship that precious few have been allowed to visit.

The large American flag flying over the wreck

My subconscious registers the looming presence of the hulk before I realize that I see it. Perhaps it is the shadow of the wreck’s mass in the sun-struck water, masked by the silt, but there, suddenly darker and cooler. My heart starts to pound and my breath gets shallow for a second with superstitious fear. This is my first dive on a shipwreck with so many lost souls aboard. I flick on my light and the blue-green hull comes alive with marine life in bright reds, yellows and oranges, some of it the rust that crusts the once pristine steel. As I rise up from the muddy bottom, I encounter my first porthole. It is an empty dark hole that I cannot bring myself to look into. I feel the presence of the ship’s dead, and though I know it is only some primitive level of my subconscious at work, I can’t look in because of the irrational fear that someone inside will look back.

Not once throughout this dive, nor ever in the dives that follow, do I forget that this ship is a tomb. But the curiosity of the archeologist overcomes the fear, and I look into the next porthole. As my light reaches inside, I see what looks like collapsed furniture and a telephone attached to a rusted bulkhead. This is the cabin of Rear Admiral Isaac Kidd, who died on that long-ago December morning. His body was never found. Salvage crews found Kidd’s ring partly melded to the steel at the top

From here, we rise up to the deck and follow it to the rim of the No. 4 turret. The turret, stripped by U.S. Navy salvagers during the war, is now a large round hole in the heart of the battleship. Half filled with silt, it has been designated as the receptacle for the urns of Arizona’s survivors, who, years after the battle, choose to be cremated and interred with their former shipmates for eternity. It is a powerful statement about the bonds forged