Icebones

by Stephen Baxter

To David and Sarah Oliver and Colin Pillinger and the

Prologue

There is a flat, sharp, close horizon, a plain of dust and rocks. The rocks are carved by the wind. Everything is stained rust brown, like dried blood, the shadows long and sharp.

This is not Earth.

Though the sun is rising, the sky above is still speckled with stars. And in the east there is a morning star: steady, brilliant, its delicate blue-white distinct against the violet wash of the dawn. Sharp-eyed creatures might see that this is a double star; a faint silver-gray companion circles close to its blue master.

The sun continues to strengthen. Now it is an elliptical patch of yellow light, suspended in a brown sky. But the sun looks small, feeble; this seems a cold, remote place. As the dawn progresses the dust suspended in the air scatters the light and suffuses everything with a pale, salmon hue.

At last the gathering light masks the moons. Two of them.

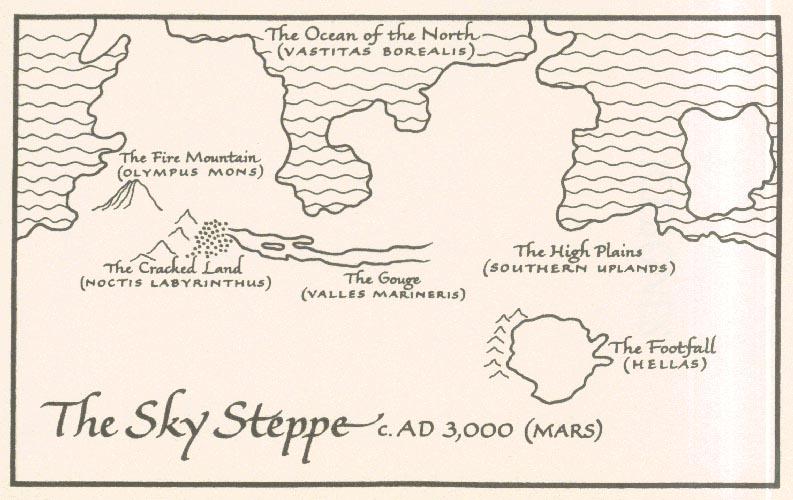

On this world, a single large ocean spans much of the northern hemisphere. There are smaller lakes and seas: many of them circular, confined within craters, linked by rivers and canals. Much of the land is covered by dark green forest and by broad, sweeping grasslands and steppe.

But ice is gathering at the poles. The oceans and lakes are crawling back into ancient underground aquifers.

The grip of ice persisted for billions of years. Now it comes again.

Soon the air itself will start to snow out.

This is the Sky Steppe.

This is Mars.

The time is three thousand years after the birth of Christ.

The rocky land rings to the calls of the mammoths. But there is no human to hear them.

Part 1: Mountain

The Story of the Language of Kilukpuk

This is a story Kilukpuk told Silverhair, at the end of her life. All this happened a long time ago, long before mammoths came to this place, which we call the Sky Steppe. It is a story of Kilukpuk herself, the Matriarch of Matriarchs, who was born in a burrow in the time of the Reptiles. But at the time of this story the Reptiles were long gone, and the world was young and warm and empty.

Kilukpuk had been alive for a very long time. She had become so huge that her body had sunk into the ground, turning it into a Swamp within which she dwelled.

But she had a womb as fertile as the sea. And every year she bore Calves.

Kilukpuk was concerned that her Calves were foolish.

Now, in those days, no Calves could talk. Oh, they made noises: chirps and barks and rumbles and snores and trumpets, just as Calves will make today. But what the Calves chattered to each other didn’t

Kilukpuk decided to change this.

One year Kilukpuk bore three Calves.

As they suckled at her mighty dugs, she took each of them aside. She said, 'If you want to suckle, you must make this sound.' And she made the suckling cry. And then, when the Calves were no longer hungry, she pushed them away.

The next day all the Calves were hungry again, and Kilukpuk waited in her Swamp.

The first Calf was silent, for she had forgotten the cry Kilukpuk taught her. And so she received no milk.

And she died.

The second Calf made the suckling cry, but made many other noises besides, for she thought that the cry was as meaningless as any other chatter. And so she received no milk.

And she died.

The third Calf, observing the fate of her sisters, made the suckling cry correctly. And Kilukpuk gathered her to her teat, and suckled her, and that Calf lived to grow strong.

When she grew up, that Calf had three Calves of her own. And all of them were born knowing the suckling cry.

Now Kilukpuk gathered the three Calves of her Calf. She said, 'If you ever lose your mother, you must make this sound.' And she made the lost cry. And then she pushed the Calves away.

A few days later, the playful Calves lost their mother — as Calves will — and Kilukpuk waited in her Swamp.

The first Calf was silent, for she had forgotten the cry Kilukpuk taught her. And so she stayed lost, and the wolves got her.

And she died.

The second Calf made the lost cry, but made many other noises besides, for she thought that the cry was as meaningless as any other chatter. And so she stayed lost, and the wolves got her.

And she died.

The third Calf, observing the fate of her sisters, made the lost cry correctly. And Kilukpuk gathered her up in her trunk and delivered her to her mother, who suckled her, and that Calf lived to grow strong.

And when she grew up, that Calf had three Calves of her own. And all of them were born knowing the suckling cry, and the lost cry.

And the next generation of Calves was born knowing the suckling cry, and the lost cry, and the 'Let’s go' rumble.

And the next generation after that was born knowing the suckling cry, and the lost cry, and the 'Let’s go' rumble, and the contact rumble.

And so it went, as Kilukpuk instructed each new generation. Calves who learned the new calls were bound tightly together, and Kilukpuk’s Family grew stronger.

Calves who did not learn the new calls died. And still Kilukpuk’s Family grew stronger.

That is how the language of mammoths and their Cousins came about. And that is why every new Calf is born with the language of Kilukpuk in her head.

Yes, it was cruel, and Kilukpuk mourned every one of those Calves who died. But it is the truth.

The Cycle is the wisdom of uncounted generations of mammoths. Nothing in there is false. For if it had been false, it would have been removed.

Just as the foolish Calves who would not learn were removed, by death.

1

The Awakening

Icebones was cold.

She was trapped in chill darkness. She couldn’t feel her legs, her tail, even her trunk. She could hear nothing, see nothing.

She tried to call out to her mother, Silverhair, by rumbling, trumpeting, stamping. She couldn’t even do that. It was like being immersed in thick cold mud.

And the cold was deep, deeper than she had ever known, soaking into the core of her body, reaching the warm center under her layers of hair and fat and flesh and bone, the core heat every mammoth had to protect, all her life.

Perhaps this was the aurora, where mammoths believed their souls rose when they died.

…But, she thought resentfully, she was only fifteen years old. She had never mated, never borne a calf. How could

Besides, much was wrong. The aurora was full of light, but there was no light here. The aurora was full of the scent of growing grass, but there was no scent here.

And things were changing.

She had been —

She recalled a time before this darkness, when she had been with Silverhair. They had walked across the cold steppe of the Island, surrounded by the Lost and their incomprehensible gadgetry, perturbed and yet not harmed by them. She recalled what her mother had been saying: 'You will be a Matriarch some day, little Icebones. You will be the greatest of them all. But responsibility will lie heavily on you…' Icebones hadn’t understood.

With her mother, then on the Island. Now here.

Everyone knew that in the aurora nothing changed. In the aurora mammoths gathered in the calm warm presence of Kilukpuk, immersed in Family, and there was no day or night, no hunger or thirst, no I: merely a continual, endless moment of belonging.

This was

But with life came hope and fear, and dread settled on her.

She made the lost cry, like a calf. But she couldn’t even hear that.