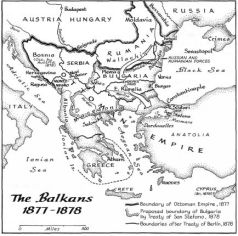

The difficult, bitter, and costly war, highlighted by such engagements as the Russian defense of the Shipka pass in the Balkan mountains and the Turkish defense of the fortress of Plevna, resulted in a decisive Russian victory. The tsarist troops were approaching Constantinople when the fighting ceased. The Treaty of San Stefano, signed in March 1878, reflected the thorough Ottoman defeat: Russia obtained important border areas in the Caucasus and southern Bessarabia; for the latter, Rumania, which had fought jointly with Russia at Plevna and elsewhere, was to be compensated with Dobrudja; Serbia and Montenegro gained territory and were to be recognized, along with Rumania, as fully independent, while Bosnia and Herzegovina were to receive some autonomy and reform; moreover, the treaty created a large autonomous Bulgaria reaching to the Aegean Sea, which was to be occupied for two years by Russian troops; Turkey was to pay a huge indemnity.

But the Treaty of San Stefano never went into operation. Austria-Hungary and Great Britain forced Russia to reconsider the settlement. Austria-Hungary was particularly incensed by the creation of a large Slavic state in the Balkans, Bulgaria, which Russia had specifically promised not to do. The reconsideration took the form of the Congress of Berlin. Presided over by Bismarck and attended by such senior European statesmen as Disraeli and Gorchakov, who was still the Russian foreign minister, it met for a month in the summer of 1878 and redrew the map of the Balkans. While, according to the arrangements made in Berlin, Serbia, Montenegro, and Rumania retained their independence and Russia held on to southern Bessarabia and most of her Caucasian gains, such as Batum, Kars, and Ardakhan, other provisions of the Treaty of San Stefano were changed beyond recognition. Serbia and Montenegro lost some of their acquisitions. More important, the large Bulgaria created at San Stefano underwent division into three parts: Bulgaria proper, north of the Balkan mountains, which was to be autonomous; Eastern Rumelia, south of the mountains, which was to receive a special organization under

Turkish rule; and Macedonia, granted merely certain reforms. Also, Austria-Hungary acquired the right to occupy, although not to annex, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and the Sanjak of Novi Bazar, while Great Britain took Cyprus. The diplomatic defeat of Russia reflected in the Berlin decisions made Russian public opinion react bitterly against Great Britain, Austria-Hungary, and, less justifiably, Bismarck, the 'honest broker' of the Congress.

Whereas Russian dealings with European powers in the reign of Alexander II brought mixed results, the empire of the tsars continued to expand grandly in Asia. Indeed, many scholars assert the existence of a positive correlation between Russian isolation or rebuffs in the west and the eastward advance. Be this as it may, there can be no doubt that the third quarter of the nineteenth century witnessed enormous Russian gains in Asia, notably in the Caucasus, in Central Asia, and in the Far

East. Also, in 1867, the tsarist government withdrew from the Western hemisphere by selling Alaska to the United States for $7,200,000.

As mentioned earlier, Georgian recognition of Russian rule and successful wars against Persia and Turkey in the first decades of the nineteenth century had brought Transcaucasia and thus all of the Caucasus under the sway of the tsars. But imperial authority remained nominal or nonexistent so far as numerous mountain tribes were concerned. Indeed, Moslem mountaineers reacted to the appearance of Russian troops by mobilizing all their resources to drive the invaders out and by staging a series of desperate 'holy wars.' The pacification of the Caucasus, therefore, took decades, and military service in that majestic land seemed for a time almost tantamount to a death warrant. Beginning in 1857, however, Russian troops commanded by Prince Alexander Bariatinsky, using a new and superior rifle against the nearly exhausted mountaineers, staged another, this time decisive, offensive. In 1859 Bariatinsky captured the legendary Shamil, who for twenty-five years had been the military, spiritual, and political leader of Caucasian resistance to Russia. That event has usually been considered as the end of the fighting in the Caucasus, although more time had to pass before order could be fully established there. A large number of Moslem mountaineers chose to migrate to Turkey.

The Caucasus needed pacification when Alexander II ascended the throne, but Central Asia had yet to be taken. That was accomplished by a series of daring military expeditions in the period from 1865 to 1876. Led by such able and resourceful commanders as Generals Constantine Kaufmann and Michael Skobelev, Russian troops, in a series of converging movements in the desert, encircled and defeated the enemy. Thus in the course of a decade the Russians conquered the khanates of Kokand, Bokhara, and Khiva, and finally, in 1881, also annexed the Transcaspian region. Russian expansion into Central Asia bears a certain resemblance both to colonial wars elsewhere and to the American westward movement. Central Asia proved attractive for commercial reasons, for the peoples of that area could supply Russia with raw materials, for example cotton, and at the same time provide a market for Russian manufactured goods. Also, Russian settlements had to be defended against predatory neighbors, and that led to further expansion. More important, it would seem that the fluid Russian frontier simply had to advance in one way or another, at least until it came up against more solid obstacles than the khanates of Bokhara and Khiva. In Central Asia, as in the Caucasus, the establishment of Russian rule usually interfered little with the native economy, society, law, or customs.

The Russian Far Eastern boundary remained unchanged from the Treaty of Nerchinsk drawn in 1689 until Alexander II's reign. In the intervening period, however, the Russian population in Siberia had increased con-

siderably, and the Amur river itself had acquired significance as an artery of communication. In 1847 the energetic and ambitious Count Nicholas Muraviev - known later as Muraviev-Amursky, that is, of the Amur - became governor-general of Eastern Siberia. He promoted Russian advance in the Amur area and profited from the desperate plight of China, at war with Great Britain and France and torn by a rebellion, to obtain two extremely advantageous treaties from the Celestial Empire: in 1858, by the Treaty of Aigun, China ceded to Russia the left bank of the Amur river and in 1860, by the Treaty of Peking, the Ussuri region. The Pacific coast of the Russian Empire began gradually to be settled: the town of Nikolaevsk on the Amur was founded in 1853, Khabarovsk in 1858, Vladivostok in 1860. In 1875 Russia yielded its Kurile islands to Japan in return for the southern half of the island of Sakhalin.

XXX

THE REIGN OF ALEXANDER III, 1881-94, AND THE FIRST PART OF THE REIGN OF NICHOLAS II, 1894-1905

The natural conclusion is that Russians live in a period which Shakespeare denned by saying, 'The time is out of joint.'

The reign of Alexander III and the reign of Nicholas II until the Revolution of 1905 formed a period of continuous reaction. In fact, as has been indicated, reaction had started earlier when Alexander II abandoned a liberal course in 1866 and the years following. But the 'Tsar-Liberator' did enact major reforms early in his rule, and, as the Loris-Melikov episode indicated, progressive policies constituted a feasible alternative for Russia as long as he remained on the throne. Alexander III and Nicholas II saw no such alternative. Narrow-minded and convinced reactionaries, they not only rejected further reform, but also did their best to limit the effectiveness of many changes that had already taken place. Thus they instituted what have come to be known in Russian historiography as 'counterreforms.' The official estimate of Russian conditions and needs became increasingly unreal. The government relied staunchly on the gentry, although that class was in decline. It held high the banner of 'Orthodoxy-autocracy-nationality,' in spite of the fact that Orthodoxy - helped, or rather hindered, by police and other more direct compulsive measures - could hardly cement together peoples of many faiths in an increasingly secular empire, that autocracy was bound to be even more of an anachronism and obstacle to progress in the twentieth than in the nineteenth century, and that a nationalism which had come to include Russification could only split a multinational state. Whereas the last two Romanovs to rule Russia agreed on principles and policies, they differed in character: Alexander III was a strong man, Nicholas II a weak one; under Nicholas confusion and