compensation that the landlords received as part of the reform went to pay debts, rather little remaining for development and modernization of the gentry economy. Moreover, most landlords failed to make effective use of their resources and opportunities. Deprived of serf labor and forced to adjust to more intense competition and other

* A

harsh realities of the changing world, members of the gentry had little in their education, outlook, or character to make them successful capitalist farmers. A considerable number of landlords, in fact, preferred to live in Paris or Nice, spending whatever they had, rather than to face the new conditions in Russia. Others remained on their estates and waged a struggle for survival, but, as statistics indicate, frequently without success. Uncounted 'cherry orchards' left gentry possession. The important fact, much emphasized by Soviet scholars, that a small segment of the gentry did succeed in making the adjustment and proceeded to accumulate great wealth in a few hands does not fundamentally change the picture of the decline of a dominant class.

If the 'great reforms' helped push the gentry down a steep incline, they also led to the rise of a Russian middle class, and in particular of industrialists, businessmen, and technicians - both results, to be sure, were not at all intentional. It is difficult to conceive of a modern industrial state based on serfdom, although, of course, the elimination of serdom constituted only one prerequisite for the development of capitalism in Russia. Even after the emancipation the overwhelmingly peasant nature of the country convinced many observers that the empire of the tsars could not adopt the Western capitalist model as its own. The populists argued that the Russian peasant was self-sufficient, producing his own food and clothing, and that he, in his egalitarian peasant commune, did not need capitalism and would not respond to it. Perhaps more to the point, the peasant was miserably poor and thus could not provide a sufficient internal market for Russian industry. Also the imperial government, especially the powerful Ministry of the Interior, preoccupied with the maintenance of autocracy and the support of the gentry, for a long time in effect turned its back on industrialization.

Nevertheless, Russian industry continued to grow - a growth traced in detail by Goldsmith and others - and in the 1890's it shot up at an amazing rate, estimated by Gerschenkron at 8 per cent a year on the average. Russian industrialists could finally rely on a better system of transportation, with the railroad network increasing in length by some 40 per cent between 1881 and 1894 and doubling again between 1895 and 1905. In addition to Russian financial resources, foreign capital began to participate on a large scale in the industrial development of the country: foreign investment in Russian industry has been estimated at 100 million rubles in 1880, 200 million in 1890, and over 900 million in 1900. Most important, the Ministry of Finance under Witte, in addition to building railroads and trying to attract capital from abroad, did everything possible to develop heavy in-

dustry in Russia. To subsidize that industry Witte increased Russian exports, drastically curtailed imports, balanced the budget, introduced the gold standard, and used heavy indirect taxation on items of everyday consumption to squeeze the necessary funds out of the peasants. Thus, in Russian conditions, the state played the leading role in bringing large-scale capitalist enterprise into existence.

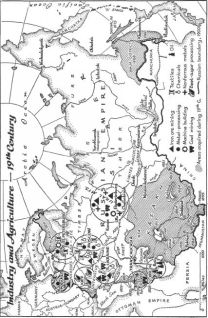

Toward the end of the century Russia possessed eight basic industrial regions, to follow the classification adopted by Liashchenko. The Moscow industrial region, comprising six provinces, contained textile industries of every sort, as well as metal processing and chemical plants. The St. Petersburg region specialized in metal processing, machine building, and textile industries. The Polish region, with such centers as Lodz and Warsaw, had textile, coal, iron, metal processing, and chemical industries. The recently developed south Russian Ukrainian region supplied coal, iron ore, and basic chemical products. The Ural area continued to produce iron, non-ferrous metals, and minerals. The Baku sector in Transcaucasia contributed oil. The southwestern region specialized in beet sugar. Finally, the Trans-caucasian manganese-coal region supplied substantial amounts of its two products.

The new Russian industry displayed certain striking characteristics. Because Russia industrialized late and rapidly, the Russians borrowed advanced Western technology wholesale, with the result that Russian factories were often more modern than their Western counterparts. Yet this progress in certain segments of the economy went together with appalling backwardness in others. Indeed, the industrial process frequently juxtaposed complicated machinery and primitive manual work performed by a cheap, if unskilled, labor force. For technological reasons, but also because of government policy, Russia acquired huge plants and large-scale industries almost overnight. Before long the capitalists began to organize: a metallurgical syndicate was formed in 1902, a coal syndicate in 1904, and several others in later years. Russian entrepreneurs and employers, it might be added, came from different classes - from gentry to former serfs - with a considerable admixture of foreigners. Their leaders included a number of old merchant and industrialist families who were Old Believers, such as the celebrated Morozovs. As to markets, since the poor Russian people could absorb only a part of the products of Russian factories, the industrialists relied on huge government orders and also began to sell more abroad. In particular, because Russian manufactures were generally unable to compete successfully in the West, export began on a large scale to the adjacent Asiatic countries of Turkey, Persia, Afghanistan, Mongolia, and China. Again Witte and the government helped all they could by such means as the establishment of the Russo-Persian Bank and the Russo-Chinese Bank, and the building of the East China Railway, not to mention the Trans-

Siberian. As already indicated, Russian economic activity in the Far East was part of the background of the Russo-Japanese War.

The great Russian industrial upsurge of the 1890's ended with the depression of 1900, produced by a number of causes, but perhaps especially by the 'increasing weakness of the base,' the exhaustion of the Russian peasantry. The depression lasted several years and became combined with political unrest and finally with the Revolution of 1905. Still, once order had been restored and the Russians returned to work, industrialization resumed its course. In fact, the last period of the economic development of imperial Russia, from the calling of the First Duma to the outbreak of the First World War, witnessed rapid industrialization, although it was not as rapid as in the 1890's, with an annual industrial growth rate of perhaps 6 per cent compared to the 8 per cent of the earlier period. The output of basic industries again soared, with the exception of the oil industry. Thus, counting in millions of

The new industrial advance followed in many ways the pattern of the previous advance, for instance, in the emphases on heavy industry and on large plants. Yet it exhibited some significant new traits as well. With the departure of Witte, the government stopped forcing the pace of industrialization, decreased the direct support of capitalists, and relaxed somewhat the financial pressure on the masses. Russian industry managed to make the necessary adjustments, for it was already better able to stand on its own feet. Also, the industry often had the help of banks, which began to assume a guiding role in the economic development of the country. But, financial capital aside, the Russian industrialists themselves were gradually gaining strength and independence. Also, it can well be argued that during the years immediately preceding the First World War Russian industry was becoming more diversified, acquiring a larger home market, and spreading its benefits more effectively to workers and consumers.

To be sure, the medal had its reverse side. In spite of increasing production in the twentieth century, imperial Russia was falling further behind the leading states of the West - or so it is claimed by many analysts, especially Marxist analysts. Just as the Russian government relied on foreign loans, Russian industry remained heavily dependent on foreign capital, which rose to almost two and a quarter billion rubles in 1916/17 and formed approximately one-third of the total industrial investment. The French, for example, owned nearly two-thirds of the Russian pig iron and one-half of the Russian coal industries, while the Germans invested heavily in the

* A

chemical and electrical engineering industries, and the British in oil. On the basis of investment statistics some Marxists even spoke of the 'semi-colonial' status of Russia! More ominously, Russian industry rose on top of a bitter and miserable proletariat and a desperately poor peasant mass.