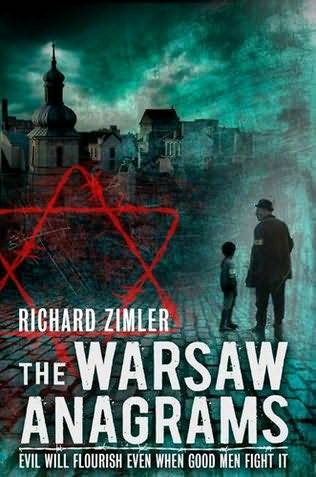

Richard Zimler

The Warsaw Anagrams

© 2011

DEDICATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For all the members of the Zimler, Gutkind, Kalish and Rosencrantz families – my many granduncles, aunts and cousins – who perished in the ghettos and camps of Poland. And for Helena Zymler, who survived.

I am greatly indebted to Andreas Campomar and Cynthia Cannell for their unwavering support. I also want to thank Nicole Witt, Anna Jarota and Gloria Gutierrez for helping my books find homes in many different countries.

I am particularly grateful to Alexandre Quintanilha, Erika Abrams and Isabel Silva for reading the manuscript of this novel and giving me their invaluable comments. Many thanks, as well, to Thane L. Weiss and Shlomo Greschem.

A number of excellent books about the Jewish ghettos of Poland helped me in my research. Prominent among them are

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

Erik Cohen’s original text for

Cohen’s manuscript of

We owe uniqueness to our dead at the very least.

Erik Cohen

PREFACE

I’ve had a map of Warsaw in the soles of my feet since I was a young boy, so I made it nearly all the way home without any confusion or struggle.

Then I spotted the high brick wall around our island. My heart leapt in my chest, and impossible hope sent my thoughts scattering – though I knew that Stefa and Adam would not be home to welcome me.

A fat German guard munching on a steaming potato stood by the gate at Street. As soon as I slipped inside, a young man wearing a tweed cap drawn low over his forehead raced past me. The flour sack he’d hoisted over his shoulder dripped dots and dashes of liquid on his coat – Morse code in chicken blood, I guessed.

Men and women lumbered through the frigid streets, cracking the crusted ice with their worn-out shoes, their hands tucked deep inside their coat pockets, vapour bursts puffing from their mouths.

In my disquiet, I nearly stumbled over an old man who had frozen to death outside a small grocery. He wore only a soiled undershirt, and his bare knees – badly swollen – were drawn in protectively to his chest. His blood- crusted lips were bluish-grey, but his eyes were rimmed red, which gave me the impression that the last of his senses to depart our world had been his vision.

In the hallway of Stefa’s building, the olive-green wallpaper had peeled away from the plaster and was falling in sheets, revealing blotches of black mould. The flat itself was ice-cold; not a crumb of food in sight.

Underwear and shirts were scattered around the sitting room. They belonged to a man. I had the feeling that Bina and her mother were long gone.

Stefa’s sofa, dining table and piano had vanished – probably sold or broken up for kindling. Etched on the door to her bedroom were the pencil marks she and I had made to record Adam’s height every month. I eased my fingertip towards the highest one, from 15 February 1941, but I lost my courage at the very last second – I didn’t want to risk touching all that might have been.

Whoever slept now in my niece’s bed was a reader; my Polish translation of

Searching the apartment rekindled my sense of purpose, and I hoped that the world would touch me back now, but when I tried to open the door to Stefa’s wardrobe, my fingers eased into the dark wood as though into dense cold clay.

What did it mean to be nine years old and trapped on our forgotten island? A clue: Adam would wake with a start over our first weeks together, catapulted from night-terrors, and lean over me to reach for the glass of water I kept on my side table. Stirred by his wriggling, I’d lift the rim to his lips, but at first I resented his intrusions into my sleep. It was only after nearly a month together that I began to treasure the squirming feel of him and his breathless gulps, and how, on lying back down, he’d pull my arm around him. The gentle rise and fall of his slender chest would make me think of all I still had to be grateful for.

Lying in bed with my grandnephew, I used to force myself to stay awake because it didn’t seem fair how such a simple act as drawing in air could keep the boy in our world, and I needed to watch him closely, to lay my hand over his skullcap of blond hair and press my protection into him. I wanted staying alive to involve a much more complex process. For him – and for me, too. Then dying would be so much harder for us both.

Nearly all of my books were gone from the wooden shelves I’d built – burned for heating, no doubt. But Freud’s

I spotted the German medical treatise into which I’d slipped two emergency matzos, but I made no attempt to retrieve them; although hunger still clawed at my belly, I no longer needed sustenance of that kind.

Eager for the comfort of a far-off horizon, I took the apartment-house stairs up to the roof and stepped gingerly on to the wooden platform the Tarnowskis – our neighbours – had built for stargazing. Around me, the city rose in fairytale spires, turrets and domes – a child’s fantasy come to life. As I turned in a circle, tenderness surged through me. Can one caress a city? To be the Vistula River and embrace Warsaw must be its own reward at times.

And yet Stefa’s neighbourhood seemed more dismal than I remembered it – the tenements further mired in