ridge behind your teeth. The

The other Klingon spellings requiring explanation are

The phonological system of the language is by design harsh, guttural, and alien, like Klingons, but it also makes a certain kind of linguistic sense. The language doesn’t include barks, growls, or other sounds not used in human languages. And the sounds it does use are not even that exotic as far as real languages go: no clicks, trills, ingressives, or voiceless vowels.

“The goal was for the language to be as unlike human language as possible while at the same time still pronounceable by actors,” I was told by Marc Okrand, the inventor of the Klingon language. “The alien character of Klingon doesn’t stem so much from the sounds it uses as from the way that it violates the rules of commonly co- occurring sounds. There’s nothing extraordinary about the sounds from a linguistic standpoint. You just wouldn’t expect to find them all in the same language.”

Okrand, who has a Ph.D. in linguistics, came to be the creator of Klingon through a happy accident involving the 1982 Academy Awards. At the time, he was working for the National Captioning Institute (where he still works), developing methods for the production of real-time closed-captioning for live television. That year’s Oscars presentation, the year of

Despite his other obligations Okrand came through on time and skillfully—the scene, between Leonard Nimoy and Kirstie Alley, had been filmed in English, and he had to create lines that could be dubbed over their mouth movements in a believable way—so two years later, when the production team of

Okrand did not just make up a list of words. Knowing that fans would be watching closely, he worked out a full grammar with great attention to detail. Klingon both flouts and follows known linguistic principles, and its real sophistication lies in the balance between the two tendencies. It gets its alien quality from the aspects that set it apart from natural languages: its phonological inventory of sounds that don’t normally occur together, its extremely rare basic word order of OVS (object-verb-subject). Yet at the same time it has the feel of a natural language. A linguist doing field research among Klingon speakers would be able to work out the system and describe it with the same tools he would use in describing a remote Amazon language.

He would quickly deduce, for example, that Klingon is an agglutinating language. Such languages, like Hungarian and Finnish, build words by affixing units that have grammatical meanings to roots, one after the other. In these languages, entire phrases can be expressed in single words. This is how the Klingon proverb “If it is in your way, knock it down” can be expressed in only two words: “

“If it blocks you, cause it to fall!”

Klingon has twenty-six noun suffixes, twenty-nine pronominal prefixes, thirty-six verb suffixes, two number suffixes, a phrasal topicalizing suffix, and an interrogative suffix. Words have the potential to be very long. The Klingon Language Institute publishes a journal called

“The so-called great benefactors are seemingly unable to cause us to prepare to resume honorable suicide (in progress) due to their definite great self-control.”

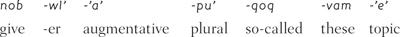

The sentence contains three roots (give, kill, control) and twenty-three affixes. Here is the breakdown:

“

“

As for these so-called great benefactors,”

“they are apparently unable to cause us to prepare to resume honorable suicide (in progress)”

“due to their defi nite great self- control.”

The functions of these affixes are common, from a linguistic point of view. The representation of causation (-