Even though this book deals with houses infested with parasites and insects, one cannot help but think of the homes of the “homeless”—shacks, bridges, cars, tents, and streets—which shelter the mass of generally shifting populations in Bosnia, Ruwanda, the United States, Latin America, and elsewhere. It is hoped that readers of this book will become more active in support of building homes for the homeless and in protecting the wild homes of animals, insects, and plants while supporting the treatment of people sick with Chagas’ disease.

From the Microscope to the Telescope

The viewpoint of the chapters is similar to an optical device that begins as a microscope and ends as a telescope, going from the infinitesimal parasite to humans, communities, nations, and continents. The world of microbiology is an amazing universe continually being newly discovered. Chapter 1, Discovering Chagas’ Disease, reveals the medical history of this disease. Chapter 2, An Early Andean Disease, contains its history in the Andes. Chapter 3,

Reversing the microscope into a telescope to examine the environment relating to Chagas’ disease, Chapter 7, Cultural and Political Economy of Infested Houses, deals with the relationship of cultural and political-economic factors in bringing into physical proximity parasites, vectors, and hosts.

What can be done to prevent Chagas’ disease is considered in the last chapters. Housing improvement projects are described in Chapter 8,

This book includes appendices to learn more about biomedical aspects of Chagas’ disease. These appendices provide information in the forms of tables and charts concerning the vector species and hosts of

The perspective of

Reading about Chagas’ disease in Bolivia gives a perspective for understanding this disease throughout Latin America and for predicting what might happen in the United States and Europe, where it is spreading. Chagas’ disease is the space in which are encapsulated minutely infinite forces and from which we might get a broader perspective of the universe.

CHAPTER ONE

Discovering Chagas’ Disease

In 1909 Carlos Chagas discovered American trypanosomiasis by intuition, induction, scientific method, hard work, genius, and a pinch of luck.[4] Carlos Chagas represents a rare example of a medical scientist who described a disease after having found its causative agent,

Chagas’ discovery coincided with conquests of the Amazon. It was a time when symbiotic microorganisms, living in animal reservoirs within the Amazon, became pathogenic for invading settlers. Such is now the case for Bolivians with Chagas’ disease.

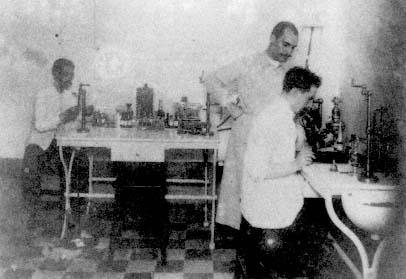

As a budding parasitologist in that discipline’s age of discovery, Carlos Chagas realized that microbiology could reveal the causes of tropical diseases. The microscope was to biology what the telescope was to astronomy. Within a generation, scientists had discovered the world of microbiology and shattered many age-old aetiologies: Robert Koch discovered the tuberculin bacterium in 1882 and liberated tuberculosis from its association with consumption, vapors, and “bad air.” Louis Pasteur isolated the rabies virus and produced an attenuated strain or vaccine in 1884. Pasteur disproved the notion that the disease resulted from nervous trauma allegedly suffered by sexually frustrated dogs (rabid men were said to be priapic and sexually insatiable) (Geison 1995:179; Kete 1988). D.D. Cunningham described leishmania organisms found in skin lesions in India in 1885; F. Schaudinn depicted trophozoites and cysts of

Carlos Justiniano Ribeiro Chagas was born on July 9, 1879, in the small town of Oliveira, Minas Gerais, Brazil, of Portuguese farmers who were descendants of immigrants who had come to Brazil in the late seventeenth century (Lewinsohn 1981). His upper-class parents owned a small coffee plantation with a modest income. When he was four, his father died, and his mother, a strong-willed farmer, raised him and three younger children. She tried to persuade him to become a mining engineer, but he refused and instead chose medical school, being swayed by a physician uncle who convinced him that for Brazil to develop industrially it was necessary to rid the country of endemic diseases. (Many European ships refused to dock in Brazilian ports because of fear of contracting yellow fever, smallpox, bubonic plague, and syphilis).

Carlos Chagas studied at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in 1902, where he wrote his M.D. thesis on the “Hematological Aspects of Malaria” (1903) under the leading Brazilian parasitologist, Oswaldo Cruz. Cruz tackled the task of ridding Rio de Janeiro of yellow fever by the systematic combat of the mosquito vector and the isolation of victims in special hospitals. He also provided vaccinations against the plague and smallpox. Eradication of vectors and mass vaccinations were revolutionary measures at this time. Many diseases were thought to be