reorganization. The extent to which he used this reshuffling to take retribution against those who had opposed him on November 5 of the previous year is indicated by the fact that Neurath, too, was dismissed, to be replaced by Joachim von Ribbentrop. Hitler also put an end to his tempestuous relationship with Hjalmar Schacht, his minister of economics, by appointing Walter Funk to that post. Finally there was the question of what to do with Hermann Goring, whom Hitler named field marshal in an attempt to appease him for having been passed over in this orgy of new appointments.

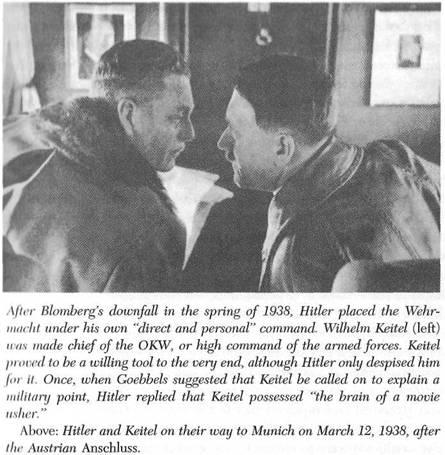

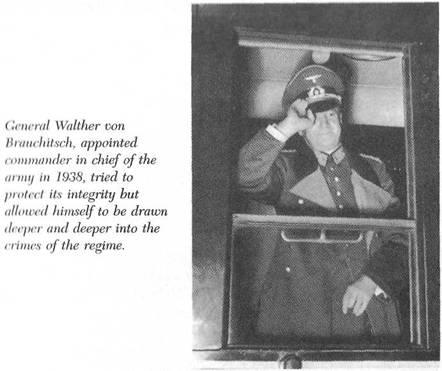

Thus the last people who could challenge Hitler were eliminated, having been systematically weakened and stripped of their authority. The new men recommended themselves to the Fuhrer through their pliancy and submissiveness, and he expected them to be nothing more than executors of his will. Wilhelm Keitel was made chief of the OKW because Blomberg, during his final interview, had disparaged him as a mere “office manager.” “That’s just the kind of man I need,” Hitler promptly replied.10 Walther von Brauchitsch, who took over as commander in chief after Fritsch, accepted the appointment reluctantly and after long hesitation, more out of a sense of duty than out of ambition. He was apolitical, like many of his fellow generals, tended to avoid conflict, and in any case was much too weak-kneed to have any hope of defending the army’s interests against Hitler, the Nazi Party, and the rising SS.

Hitler’s impatience and the hectic pace of events are almost palpable in the extant documents from this period. Within days of issuing his February 4 decree, he ordered that the materiel needed for army mobilization be “fully” stockpiled by April 1, 1939. Furthermore, he ordered plans to be drafted for a far-reaching naval program that would enable Germany to compete with Great Britain on the high seas and for a fivefold expansion of the Luftwaffe. At the same time, great strides were made on the operational side. Hitler’s heady restlessness of that spring suggests that he was deeply gratified to be free at last of the incessant obstructionism of the old-line generals, with their frowning brows and shaking heads. Now he could pursue his dreams of grandeur and glory unimpeded and “save” the world according to his own vision. On the evening of April 20, 1938, he asked Keitel to head up general staff preparations for the occupation of Czechoslovakia. At about the same time, the chief of general staff, Ludwig Beck, drafted the first of a series of memoranda composed with mounting alarm over the next few months in an attempt to dissuade Hitler from going to war and also to restore the military’s political influence through internal reorganization. That was the beginning of a long, drawn-out duel between unequal opponents. In mid-June Hitler announced that he would take any opportunity that arose after October 1 “to solve the Czech question.”

Although the period between the Rohm and Fritsch affairs was marked by error and blundering, what stands out above all was a lack of will and assertiveness. In its pedantic, exacting way, history almost always requites such failings with shame and humiliation. In the case of Fritsch, not a single general insisted with appropriate vigor on clarifying the circumstances surrounding his denunciation or even on knowing the reasons, which Hitler only vaguely hinted at, that Fritsch could not be fully and publicly exonerated. Still, Brauchitsch interceded persistently and quietly on Fritsch’s behalf and, by pointing to the mounting disquiet in the army, eventually did persuade the Fuhrer to explain himself to the officer corps.

The meeting was held on June 13 at the air base in Barth, where, according to all reports, Hitler delivered one of the most compelling speeches of his career. With an eye toward his ripening plans for military conquest, he was determined to forestall the looming crisis of confidence in the army. He spoke of his “regrets” and the “tragedy” of the Fritsch case and promised that a similar situation would never arise again. His every word implied that the army remained the unchallenged and unchallengeable bearer of arms in the Reich, and he concluded by announcing that General Fritsch would be appointed “honorary commander” of the Twelfth Artillery Regiment.

But the army’s irretrievable loss of influence in the wake of the Fritsch affair became apparent as early as the next March, when the German incursion into Austria was planned without the consultation of the general staff. As if freed of his bonds, Hitler dared for the first time to send German forces across international frontiers, in an operation planned largely by party circles and carried out with the support of Himmler and the SS, whose star was plainly in the ascendant.

Werner von Fritsch, though now cleared of all charges, was put through one final humiliation. Hitler delayed communicating with him until March 30, when a chilly letter was finally sent out, followed two days later by a curt announcement in the press that the Fuhrer had conveyed to General Fritsch his “best wishes for the recovery of his health.” Fritsch responded one week later in a letter to Hitler: “The criminal charges against me have totally collapsed. However the deeply hurtful circumstances surrounding my dismissal from the army linger on-all the more painfully since the true reasons for my dismissal have not remained unknown to many in the Wehrmacht and the general public.” Fritsch pleaded that “those people be called to account who were officially responsible for my case and for keeping you fully and promptly informed” and entrusted the restoration of his honor “to your wise judgment as commander in chief.” He never received a reply.31

The Fritsch affair marked one of the lowest points in the long history of the German military. It also marked a new departure in the history of the Nazi regime, for the events of the spring of 1938 prompted the first stirrings of underground resistance. Groups materialized in a variety of locations, largely the creation of individuals who recognized not only the threat Hitler posed to Germany but the extent to which his behavior fell short of civilized standards. They formed ties, attracted like-minded people, and even overcame deeply entrenched European chauvinisms by reaching out across national borders to seek support abroad. They still differed immensely in their hopes and intentions and their readiness to shed the prejudices of the past; uniting them was little more than the conviction that things could not simply be allowed to take their course.

The most prominent figure in these opposition groups was indisputably Hans Oster, who became chief of the central division of the OKW Military Intelligence Office in the autumn of 1938. He had been skeptical of the Nazis prior to 1933 but, like most of his fellow officers, initially approved of Hitler’s foreign policy and therefore hesitated for a time once the new regime came to power. The Rohm affair served to clear his mind. Though not particularly politically minded at first, he nevertheless possessed sufficiently strong values and clarity of vision to understand the devastating defeat that the Reichswehr had inflicted on itself. The despotism in the land, daily growing more palpable in countless ways, the curtailment of the rule of law, and the emerging struggle against the churches prompted this parson’s son from Dresden to progress from mere reservations about the regime to fundamental hostility toward it. This inspired him to use the resources of Military Intelligence to build a far-flung network of conspirators. The disgraceful farce leading to Fritsch’s dismissal fired Oster with a determination to resist, though he recognized that it was Fritsch’s own weakness that had made his downfall inevitable. Nevertheless, Fritsch had been Oster’s regimental commander for a number of years and Oster continued to hold him in the highest regard, almost revering him. Decisive, quick-witted, and diplomatically imaginative, Oster was an unusual blend of moral rectitude, cunning, and recklessness. During many long discussions with Beck, he pointed out all the inconsistencies in the chief of the general staffs position and sowed doubt about the formalistic concept of loyalty to which Beck always hewed when Hitler repeatedly forced tests of conscience on him. Constantly on the move, Oster cultivated contacts on all sides and forged connections between the civilian and military opponents of the regime that would later become very important.

The driving force of the civilian opposition was Carl Goerdeler, whom the military resistance also came over the years to recognize as a leading figure. The scion of a conservative family, he originally joined the German National People’s Party but left because of its narrow, reactionary views. Goerdeler then earned a reputation for being a broad-minded, socially progressive politician as mayor of Leipzig. In the Weimar period, under Chancellor Bruning, he had served as Reich commissioner for price control. Now, after the Rohm affair, he agreed to assume this position once again but soon found himself in conflict with both Hitler’s economic policy and the party authorities. He was a “classic exemplar” of that opposition from within which seeks to civilize the regime by cooperating with it.32 Whereas many people later claimed that they had cooperated with the Nazis in order to prevent even worse from happening, when they had actually demonstrated little courage and achieved virtually nothing, Goerdeler proved to be an indefatigable and public adversary of Nazi criminality in his attempt to bolster “the forces of good in the party.”33 In 1933 he refused to raise the swastika flag at the Leipzig city hall. After some vacillation he finally resigned in 1937, when, in his absence and contrary to his explicit instruction, a monument to Felix Mendelssohn, a Jew, was removed from its position in front of the Gewandhaus