pretenses and subterfuges to which opponents of a totalitarian system had to resort. In the end, many in Britain could hardly distinguish between Hitler and these self-described opponents of his who seemed to endorse so many of his demands. “There is really very little difference between them. The same sort of ambitions are sponsored by a different body of men, and that is about all,” wrote Vansittart, even though he was quite sympathetic toward the main purpose of the emissaries, namely a firm stance toward Hitler. Hugh Dalton, future chancellor of the exchequer, remarked sarcastically that these German conservatives were nothing more than “a race of carnivorous sheep.”9 Finally, there was the conviction in Britain, by no means confined to readers of the gutter press, that Germans were innately evil, or at any rate inclined to be so, as a result of their historical and cultural heritage. Cast in this light, Hitler’s conservative opponents did not seem much different from the Fuhrer himself, and considering the sins of Germany’s elites extending back to the days of the kaisers, they were certainly no better.

One additional consideration actually weighed in favor of Hitler against his opponents. It was well known that the Junkers had always been more strongly oriented toward the East than toward the West and had long had many interests in common with Russia, in addition to their neighborly, cultural, and even emotional ties; no one could rule out the possibility that this group would not one day come to an understanding with the Soviet Union-as they had before with Russia-ideological impediments notwithstanding. Hitler, on the other hand, clearly lay above all reproach in this regard. Whatever else might be said about him, he was genuinely opposed to Communism, which was spreading into Western Europe through the Front Populaire in France, the Spanish civil war, and countless activities, mostly underground. Hitler himself described Germany under his leadership as a bulwark against the tide of Communism. He told Arnold Toynbee that he had been placed “on earth to lead humanity in its inevitable struggle against Bolshevism.”10 To people who saw the world in such sweeping, categorical terms, Hitler’s illegal acts and despotic style must have shrunk to relative insignificance, or at least seemed minor problems that the Germans themselves could handle. Hitler’s alien, sinister aura only heightened his credibility as the commander of a last bastion of Western civilization against the Communist hordes.

The efforts of the German conspirators were stymied by these as well as many other misunderstandings and misconceptions, which replicated on an international level the same delusions about Hitler shared by his would-be partners in domestic politics. In the end, therefore, there were insurmountable obstacles to any meeting of minds with the British, and if anything, the distance between the conspirators and the British only grew. When von Trott tried to prod Chamberlain in the direction of the German opposition, his words were received “icily.” The ultimate reason for the countless misunderstandings in which the talks finally bogged down was clearly the two sides’ mutual lack of understanding. The Germans, especially those who had British ancestors, had studied in Britain, or took a particular interest in the country, greatly admired the vast British Empire. They invoked it frequently and, to the discomfort of their hosts, often expressed their hope that Germany might one day achieve for itself some modicum of the hegemony that Britain had over the world. The British tended to interpret this as a manifestation of the old Teutonic ambitions and the insatiable German desire for a “place in the sun” that had challenged Britain’s own status in the world for generations. Neither side perceived that the era of the great empires was actually drawing to a close, that imperialism had already become a relic of the past.

In the end, all that remained was disappointment and bitterness, and there is certainly some truth in the description of all these futile efforts as an Anglo-German tragedy. However, it was not only clumsiness and short- sightedness that led to failure; there were also conflicting interests at issue. With the signing of the Hitler-Stalin pact in August 1939, the increasingly half-hearted contacts seemed to die away. They flickered to life again here and there, before disappearing completely toward the end of the war. Fifty years later British historians are beginning to speak of Whitehall’s “needless war” against Hitler’s domestic opponents.11

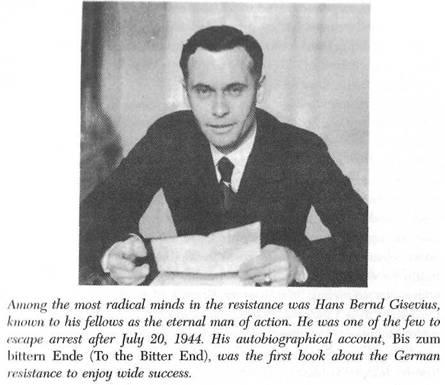

Despite the setbacks suffered by the resistance during these weeks, Oster remained undaunted. The clearer it became that Hitler was leading Germany straight into another war, the more numerous and open his opponents became. The opposition circles that had formed in the Foreign Office and in Military Intelligence were now joined by Hans Bernd Gisevius, a former assistant secretary in the Ministry of the Interior with an extensive knowledge of all the cliques and coteries in the corridors of power; Count Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, an assistant secretary to the Reich price commissioner; and Helmuth Groscurth, chief of the army intelligence liaison group on the general staff. All of them had friends in whom they confided as well as superiors and subordinates whom they informed and drew into opposition circles. Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, for instance, won over the prefect of police in Berlin, Count Wolf-Heinrich von Helldorf; even more importantly, Oster revived his old connections with Erwin von Witzleben, the commander of the Berlin military district. Witzleben was a simple, unpretentious man with clear judgment. During one of his conversations with Oster in the summer of 1938, he did not hesitate to declare himself ready for action: “I don’t know anything about politics, but I don’t need to in order to know what has to be done here.”12

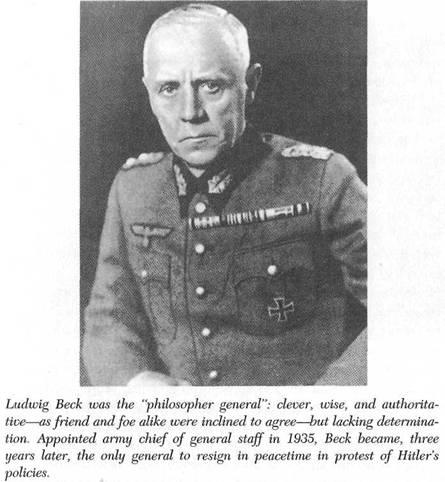

Beck was continuing his efforts and for the first time he began to break out of the realm of mere counterproposals. At a meeting with Brauchitsch on July 16, he suggested that the generals join together to form a united opposition front. If this failed to sway Hitler and he continued on a course toward war, the generals should resign enmasse. “Final decisions” needed to be made, Beck wrote, arguing that if the officer corps felled to act its members would incur a “blood guilt… . Their soldiers’ duty to obey ends when their knowledge, their conscience, and their sense of responsibility forbid them to carry out an order. If their advice and warnings are ignored in such a situation, they have the right and the duty before history and the German people to resign.”13

Brauchitsch summoned the generals to a meeting on Bendlerstrasse on August 4. It soon became apparent that all the commanding generals believed that a spreading war would prove catastrophic for Germany. Busch and Reichenau, however, did not think that an attack on Czechoslovakia would necessarily lead to war with the Western powers, and as a result the tormented Brauchitsch did not even mention Beck’s proposal that the generals attempt to pressure Hitler by threatening mass resignation. At the end of the meeting Brauchitsch did, however, reconfirm their unanimous opposition to a war and their conviction that a world war would mean the destruction of German culture.14 Shortly afterwards, Hitler was informed about the meeting by Reichenau and he immediately demanded Beck’s dismissal as chief of general staff. To show his displeasure he invited neither Beck nor Brauchitsch to a conference at his compound on the Obersalzberg on August 10; there he informed the chiefs of general staff of the armies and the air force that he had decided to invade Czechoslovakia.

Eight days later Beck submitted his resignation. This step and the way in which it was taken revealed once again the submissiveness and political ineptitude of the officer corps. After the Fritsch affair Beck had declared that he must remain at his post in order both to work for the rehabilitation of his humiliated superior and to prevent the reduction of the army to a mere tool of the Fuhrer. His ensuing dispute with Hitler, however, which took the form of a series of memoranda opposing the Fuhrer’s plans for war and for the reorganization of the high command, proved to be the “final battle” of the officer corps in its struggle to maintain a say in decisions of war and peace.15 Now Beck cleared himself out of Hitler’s way, as it were, becoming merely an outraged, and later despairing, observer without position or influence.

Only a few days earlier Erich von Manstein, his chief of operations, had written him a letter urging that he remain at his post because no one had the “skill and strength of character” to replace him. Beck’s authority was indeed widely acknowledged throughout the officer corps. He was a clear, imaginative, rigorous thinker of great integrity. Even Hitler could not shake the aura of easy superiority Beck projected in every word and deed. During the Fritsch crisis the Fuhrer had confided in a member of his cabinet that Beck was the only officer he feared: “That man could really do something.”16 Later Beck effortlessly assumed a leadership role in the opposition. No one doubted that if a successful putsch was launched he would become chief of state. “Beck was king,” a contemporary recalled.17 If there was a flaw in his cool, pure intelligence, it lay in his lack of toughness and drive. He was “very scholarly by nature,” one of his admirers commented. Other opposition figures also found that he provided more analytical acuity than leadership at crucial moments.18

Beck was also probably less of a political strategist than the situation required and was certainly not conversant with the kinds of maneuvers and ploys at which Hitler was so adept. That is why he readily acquiesced to Hitler’s request that his resignation not be made public lest it provoke an unfavorable reaction. As a result, the decision he had made after so much painful reflection had no public impact. Beck later admitted that he had made