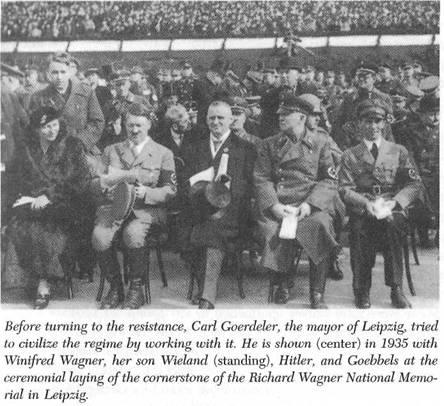

concert hall.

From this point on, Goerdeler devoted himself tirelessly to the resistance. He mobilized acquaintances from far and wide. Just between June 1937 and late 1938 he traveled to twenty-two countries, always seeking to persuade the major powers to adopt an unyielding posture toward Hitler. Within Germany he established contacts on all sides and in this way contributed immensely to rallying the conservative, nationalistic, bourgeois opposition to the regime. He was motivated in all this by an indomitable, almost pathological optimism and unshakable faith in the power of logical argument. Even as a condemned prisoner on the eve of execution, he remained true to this belief despite his experiences and his fits of resignation.

Oster and Goerdeler were just the pivotal figures among a rapidly expanding corps of people who were prepared to oppose the regime. Some were lone wolves unattached to any group. In addition to the major circle within the army was another, at the Foreign Office, led by Adam von Trott zu Solz, Otto Kiep, Eduard Brucklmeier, Hans-Hernd von Haeften, and the Kordt brothers. In the wake of the Fritsch affair, these conspirators were joined by Georg Thomas, the OKW armaments chief; generals Wilhelm Adam, Erich Hoepner, Carl-Heinrich von Stulpnagel, and Erwin von Witzleben; Chief of Military Intelligence Wilhelm Canaris; and numerous other figures. The Fritsch affair had proved a turning point for Hans von Dohnanyi and Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, too, and Henning von Tresckow even pondered quitting the army and its all-too-acquiescent generals.34

Ludwig Beck’s behavior reveals how difficult many officers found it to cast military tradition and principle aside and enter an entirely new world. In his memoranda and the comments he made to those around him, Beck repeatedly and vigorously denounced Hitler’s impatient warmongering. At the same time he struggled stubbornly, albeit in increasing isolation, to save the battered “two pillar” theory of the state and assert what was left of army influence over political life, now that Brauchitsch had clearly given up and was completely occupied with slaving off further demands rather than with making ones of his own. When Oster approached Beck at this point and asked him to take action, the chief of general staff agreed to persuade Brauchitsch to support a mass resignation of generals. At the same time, however, Beck was concerned that his name not become associated with the things that were still unacceptable to him as a soldier, such as mutiny and government by South American-style juntas.

Mass action on the part of German generals was certainly not without incalculable risk. It would be taken as signaling an uprising, for which there was not the necessary broad support, in either the army, the middle class, or the working class. It might also play into Hitler’s hands, providing him with an opportunity to flood the army with officers loyal to the regime, possibly even plucked from the senior ranks of the SS. Their resignations might enable the Fuhrer to succeed even more swiftly in creating an army that conformed ideologically to his worldview, which was more obviously becoming his aim with every passing day.

For these reasons, Beck’s plan was to present the idea of the mass resignation of the army as an attempt to save Hitler from the clutches of the party and the SS-a fiction, to be sure. The rallying cry he intended to issue was, “For the Fuhrer, against war, against rule by the bosses, for peace with the church, freedom of speech, and an end to Cheka methods!”35 This approach was based on the widespread impression that Hitler’s entourage was split into “good” and “bad” factions struggling for the heart and soul of the Fuhrer. Everyone must help, therefore, reduce the influence of the “bad” elements around Ribbentrop, Himmler, and Goebbels. This was certainly the thinking behind Beck’s comment to Brauchitsch at the time that he was prepared to shoot at the SS but not at Hitler.

Beck’s doubts about the generals’ strike were, in fact, well-founded, supported as they were by his realistic assessment of the situation. Any plan would have had to come to grips with the fact that this was a popular regime, headed by a man who had proved successful, was widely admired, and had just seen his support driven to new heights by the triumphant annexation of Austria. The regime, in its populism, was not unlike many people: egotistical, ruthless, and unconstrained by traditional values. Against it stood an Old World, elitist and confined by outmoded conventions that even it was struggling to shake off. A case in point: when Fritsch learned more about the background of the charges levied against him, he complained bitterly about his treatment and finally even conceded that Hitler had been as involved as Himmler; nevertheless, he refused to protest because that would have been rude and inappropriate for a person of his social standing. Fritsch’s inability to come to terms with the coarse new world in which he suddenly found himself is evidenced in his almost comic yet poignant plan, devised with Beck’s approval, to challenge Himmler-whom Fritsch believed had engineered the scandal-to a duel.

Until that day in January when Fritsch was suddenly confronted with a bribed witness before a host of onlookers, he and his army had thought that their position in the Reich was unassailable, that they had emerged victorious from the power struggle or at least were coasting toward inevitable victory. Now all such illusions were shattered. Despite his assurances that the Wehrmacht was and would remain the sole bearer of arms in the land, Hitler moved in August to elevate the SS to a kind of fourth service alongside the army, air force, and navy, thus laying the foundation for the emergence of the Waffen-SS. Venerable institutions are much more commonly laid low by their victories than by their defeats, especially when the true nature of those triumphs is disguised-as it so often is-or when it transpires that they are not in fact victories at all.

3. THE SEPTEMBER PLOT

Scarcely had Hitler finished basking in the jubilation, the flowers, and pealing bells that greeted him on his triumphant journey through Austria to the Heldenplatz in Vienna, when he became impatient for new adventures. At that very moment, however, forces were beginning to stir that would work with great determination to change the course that Germany was taking. The Fritsch affair had demonstrated to Hans Oster just how difficult it would be to persuade the generals to mount the kind of resistance that he deemed necessary. Regardless of how alluring they may have found Hitler’s increasingly open plans for military expansion, they feared his gambler’s instincts and the recklessness with which he risked war, even with Great Britain. Most remained paralyzed, however, inhibited from taking serious action, partly by the personal oaths of allegiance they had sworn to the Fuhrer and partly by their ingrained belief in such ideals as loyalty and obedience.

Oster and his friends realized that even though Hitler had already demolished any basis for such loyalty, it persisted and could only be uprooted through the threat of a major foe. Only if the British adopted a determined, unyielding stance that drove home the danger of another great war would the generals realize the seriousness of the threat Hitler posed to his own country. Finally they would be seized with their responsibility for the greater whole, regardless of their oaths of allegiance and traditional duty to obey.

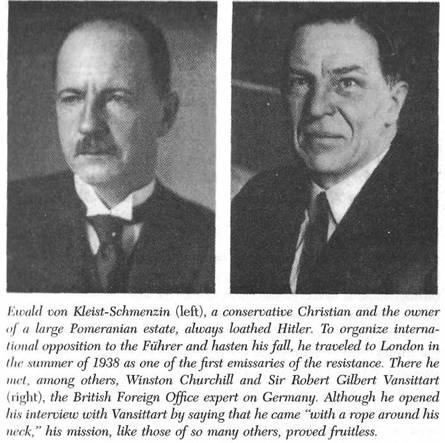

This was the thought that prompted the curious pilgrimage to London and Paris beginning in the summer of 1938. Envoys of the opposition hoped to inform the Western powers of Hitler’s intentions toward Czechoslovakia and to elicit strongly worded declarations of Western determination to oppose such aggression. Driven by his own restiveness, Goerdeler had traveled to Paris in early March and then again in April, meeting with the most senior official in the Foreign Ministry, Alexis Leger, but failing to obtain much more than fine words. In fact, many comments made at the time suggest that the French did not know what to make of a German who would warn a foreign power about the designs of his own government. No one seemed quite certain that Goerdeler was not actually acting on behalf of the Nazi regime. He aroused the same irritation in London. The extent to which the nations of Europe were caught up in their own preoccupations in those years can be seen in the fact that Sir Robert Albert Vansittart, the chief diplomatic adviser to the British Foreign Office, felt called upon to point out during their first conversation that what his visitor was doing amounted to nothing less than high treason.1

Oster’s chosen emissary was Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin, a worldly, courageous, and selfless conservative from Pomerania. In mid-January 1933 he had sought an interview with Hindenburg in a vain attempt to prevent Hitler’s nomination as chancellor and had subsequently withdrawn in disdainful rage to his country estate. On several occasions he had already approached English friends with warnings about Hitler’s expansionist designs. Now he traveled to London with an assignment from Ludwig Beck: “Bring me back certain proof that England will fight if Czechoslovakia is attacked, and I will put an end to this regime.”2 Kleist began his meeting with Vansittart by informing the chief diplomatic adviser that he came “with a rope around his neck.” Everything