but under the circumstances he did not approve of murdering him in the open- perhaps an accident could be arranged, or they could pin the assassination on a third party. The radicals among the conspirators, who had always considered Halder indecisive, felt their doubts about him confirmed, and they began to fear for the operation, especially since the chief of general staff had explicitly reserved to himself the right to issue the order for the coup. Witzleben stated that if necessary he would take action without orders from above, cordoning off the former quarters of the Ministry of War and army headquarters and putting Halder and Brauchitsch “under lock and key during the crucial hours.”29

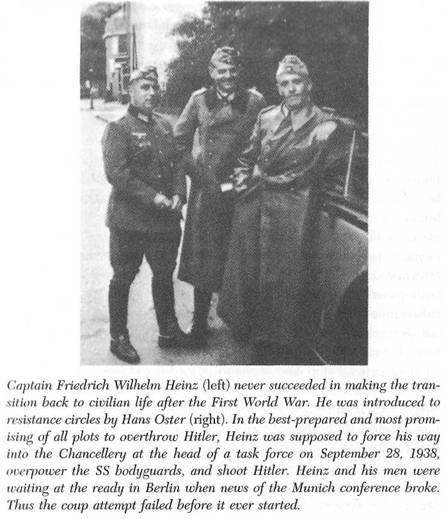

Around September 20, the innermost circle of conspirators met in Oster’s apartment for a final conclave: Witzleben, Gisevius, Dohnanyi, and probably Goerdeler, as well as Captain Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz and Lieutenant Commander Franz Maria Liedig. Heinz and Liedig had recently been asked to assemble a special task force, whose precise mission the assembled group now determined. When Halder issued the signal for the coup, the task force, under Witzleben’s command, was to overpower the sentries at the main entrance to the Reich Chancellery at 78 Wilhelmstrasse, enter the building, neutralize any resistance, especially from Hitler’s bodyguards, and enter Hitler’s quarters. The Fuhrer would then be arrested, the conspirators agreed, and immediately transported by automobile to a secure location.

Oster had arranged for Heinz to come to the meeting with Witzleben. Molded by his experiences in the Great War, Heinz, like many of his counterparts, had never felt at ease in civilian life and had continued to live by military habits. Initially a member of the Ehrhardt Freikorps, a private army formed after the First World War, he was swept up by the mood of romantic-revolutionary nationalism and joined the Stahlhelm, the paramilitary association that provided a home for restless members of the political right during the days of the much-hated republic but that, like all other political organizations, was dissolved in the great

Witzleben had scarcely left Oster’s apartment when the remaining conspirators expanded the plot in one key way. Heinz argued that it would not suffice simply to arrest Hitler and put him on trial. Even from a prisoner’s dock, Hitler would prove more powerful than all of them, including Witzleben and his army corps. Heinz’s arguments seemed to strike home. In the wake of the nationalistic euphoria over Austria’s “return” to the Reich, Hitler’s position was stronger than ever; the regime’s propaganda machine had succeeded in portraying the Fuhrer as the stalwart champion of the national interest. It was only the malevolent or corrupt forces in his entourage, according to some critical voices, who occasionally led him astray. Heinz therefore argued that it was essential to engineer a scuffle during the arrest and simply shoot Hitler on the spot.

If the records are not misleading, Oster finally agreed, although he knew that both Witzleben and Halder were opposed on principle to murdering Hitler. And thus a third conspiracy arose within the already existing “conspiracy within a conspiracy.” It comprised the most determined core of conspirators-those who would stop at nothing. In hindsight, they were perhaps the only ones who might have been a match for the Nazis. All the others, including Halder, Beck, and even Witzleben, were impeded by their notions of tradition, morality, and good upper-class manners, though there were considerable individual differences among them. The resistance was therefore never really able to match the ruthlessness of the regime. Indeed, a few days after this evening conference, Beck warned Oster that the conspirators should not defile their good names by committing murder. The debate surrounding this issue would continue unabated until July 20, 1944.

Nevertheless, all now stood ready for the coup. What remained was the signal from Halder, to be given as soon as Hitler issued the orders to invade. But on the evening of September 13 stunning news arrived. The British prime minister had declared his willingness to hold personal discussions with the Fuhrer, immediately, at any location and without concern for protocol. Hitler is said to have commented later that he was “thunderstruck” by Chamberlain’s action. For the conspirators, it was as if the world had come crashing down around them. As one of their number later wrote, they each struggled to maintain their composure; those who had advocated a more cautious approach heaped scorn on the irresponsibility of the activists who once again had underestimated the genius of the Fuhrer. Witzleben expressed doubts about the judgment of the conspirators who claimed to be political experts. Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt voiced his concern that the conspirators would now no longer be able to count on the army troops that were crucial to a successful coup. In a mood of glum uncertainty, most of the conspirators began to fear that the ground had been torn out from under them once and for all.

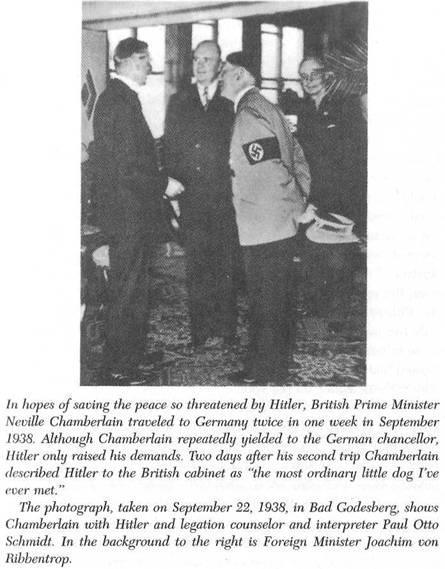

Ultimately, the overture to Hitler only proved something that Chamberlain had never been willing to acknowledge but that certainly must have begun to dawn on him within a few bitter days: Hitler wanted not to resolve the crisis in Europe but to heighten it. The Fuhrer felt confirmed in his belief that the Western democracies would yield in the end when Chamberlain accepted the transfer of the Sudetenland to Germany, a decision endorsed by the British and French governments after nervous negotiations, and even accepted by Prague, though it consented only under great pressure.

Hitler was nevertheless surprised when, one week later, on September 22, 1938, the prime minister flew to Bad Godesberg, near Bonn, to deliver a copy of the agreement personally and to discuss the modalities of the transfer. Paradoxically, such eagerness to appease actually complicated Hitler’s plans for further annexations by ruining the triumphant march into Prague that he was already savoring. After an embarrassed pause, Hitler quietly informed Chamberlain that the agreement they had reached in Berchtesgaden just a week before was null and void. He now insisted not only on marching immediately into the Sudetenland but also on satisfaction of longstanding Polish and Hungarian claims on various border regions of Czechoslovakia. After an exchange of letters from the respective staffs failed to resolve these issues, the negotiations were broken off that evening. An enraged Chamberlain demanded a memorandum setting forth the new Germany requirements. According to Ernst von Weizsacker of the Foreign Office, Hitler “clapped his hands together as if in great amusement” when he described the course of the conversations. Three days later he issued an ultimatum: he would only hold his divisions back if his new Godesberg demands were accepted by 2:00 p.m. on September 28. “If England and France want to attack,” he told the British emissary Sir Horace Wilson, who had come to Berlin on September 26 in a final attempt to reach an agreement, “then let them do so. I don’t care. I am prepared for all eventualities. Today is Tuesday. Next Monday we’ll be at war.”30

Just as news of Chamberlain’s trip to Berchtesgaden had virtually paralyzed the conspirators, Hitler’s additional demands in Godesberg infused them with new life. When Oster heard the details from Erich Kordt, he said, “Finally [we have] clear proof that Hitler wants war, no matter what. Now there can be no going back.”31

Everywhere in Europe war preparations began, accompanied by the darkest forebodings. By the time the first news arrived from Bad Godesberg, Czechoslovakia had already ordered its forces to mobilize, not without some sense of relief. Britain followed suit, ordering the navy to make ready for war. In London, slit trenches were dug, gas masks distributed, and hospitals evacuated. France called up the reserves. In Germany, Goebbels’s propaganda campaign about the suffering of the Sudeten Germans, which had been launched just weeks before, grew shriller and shriller. Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht attack units to advance from their assembly areas in the interior to the launch points on the Czech border. In an attempt to stir up war fever in Germany, Hitler ordered the Second Motorized Division to pass through Berlin on its way to the border. It rumbled down the Ost-West- Achse boulevard, before turning into Wilhelmstrasse, where he reviewed it from the Chancellery balcony. Contrary to all expectations, however, no cheering throngs lined the streets. Hitler noted with annoyance the solemnity of the passersby and the glacial silence with which they observed the troops before turning away. Visibly upset, he withdrew into the middle of the room. The American correspondent William Shirer observed that this was the most striking antiwar demonstration that he had ever seen.32

What disappointed Hitler only encouraged the conspirators, who now moved to