In fact, the ultimatum did not expire until 2:00 p.m. the next day. That morning Oster forwarded to Witzleben a copy of the note that Hitler had sent to Chamberlain in Bad Godesberg abruptly rejecting the British offers. Witzleben immediately took it to Halder. As Halder read it, “tears of indignation” welled up in his eyes, and together the two decided not to wait any longer. Halder offered to inform Brauchitsch and rally him to the cause, if possible, especially since he himself did not have direct command over any troops in his position as chief of general staff.

Commander in Chief Brauchitsch was also outraged by Hitler’s note. He, too, began to see through the Fuhrer’s duplicity. “So he lied to me again!” he roared. But Brauchitsch was not yet prepared to commit himself to a coup at this point. He would “probably” participate, Halder reported to the waiting Witzleben upon his return. Witzleben thereupon telephoned the commander in chief right from Halder’s office and appealed to him—“virtually begging him,” according to Gisevius, “to issue the order to go ahead.” The indecisive Brauchitsch said, however, that he wanted first to stop in at the Chancellery to assess the situation personally. Upon returning to military district headquarters on Hohenzollerndamm, Witzleben called out to Gisevius, “Any time now, Doctor!”34

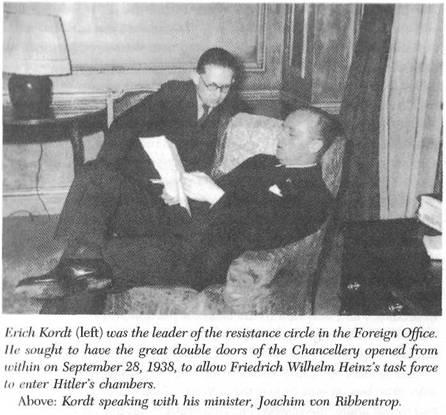

At eleven o’clock, Erich Kordt was informed by his brother in London that Great Britain would declare war if Czechoslovakia was invaded. Paris, too, seemed resolute. But German war preparations continued nevertheless. The previous evening Hitler had ordered the divisions on Germany’s western borders to mobilize as well. Kordt met Schulenburg, and they agreed to clear the way for Heinz’s task force by opening from the inside the guarded double doors at the entrance to the Chancellery. Everyone waited: Witzleben, Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt, Oster, Kordt, Gisevius, Heinz, and the others. Most important of all, Halder waited for Brauchitsch to return from the Chancellery. And then the clock stopped ticking.

At literally the last minute, Hitler decided to yield to pressure from Mussolini and agree to a conference in Munich to settle the Sudeten issue. The conspirators were aghast. After all their planning, this was clearly the end of their plots. The issue had been clear-either a coup or war-and now the Munich conference threw everything into question. Only Gisevius, arguing desperately, tried to persuade Witzleben to stage the coup anyway. But the general asked him sharply, as Gisevius later recalled, “What can the troops possibly do against a leader this victorious?”35

In an instant the situation was turned upside down. The dread of war that had haunted the morning hours gave way to jubilation and relief that afternoon. When the news was announced in the British House of Commons, there was a moment of stunned silence and then un outburst of joy. Everywhere the reaction was the same, and the few unhappy or chagrined voices were soon drowned out by cheers. When Winston Churchill denounced the Munich agreement as the “first foretaste of a bitter cup,” he was shouted down by indignant members of Parliament.36

Among the few who took little joy from the news of this day was Hitler himself. He had seemed pale and agitated during the Munich conference, often standing with his arms crossed, staring darkly ahead. “This fellow Chamberlain has spoiled my entry into Prague,” Schacht heard him say. Although historians now have little doubt that Germany would only have been able to hold out for a few days against an invasion by the Western powers in the fall of 1938, Hitler still felt that he had been cheated of his grand timetable. The depth of the rancor and disappointment he felt over the Munich conference is reflected in the thoughts he expressed while holed up in his bunker in February 1945: “We should have gone to war in 1938,” he said. “That was our last chance to keep it localized. But they gave in everywhere. Like cowards they yielded to all our demands. So it was very difficult to initiate hostilities.”37 The general public, unaware of Hitler’s determination to go to war-and even of Britain’s successful efforts to get Mussolini to intervene-concluded that the Fuhrer could master any situation. He seemed magically in league with chance, luck, with the very fates themselves.

Among the losers at Munich were Hitler’s domestic opponents. In a single day, as one of them noted, they had been reduced from powerful foes of the regime to a “bunch of malcontents” whose ideas had been disproved by events time after time and who had now become nothing more than a police problem.38 But worse yet, the Munich accord was a devastating indictment of their political judgment and could not help but tarnish their reputations. The conspirators fell into a mood of bitter helplessness, and the ties among them- already weak in many cases-slackened further or were severed completely. Feelings of mutual distrust began to arise, and many resistance leaders, such as the diplomat Ulrich von Hassell, began to doubt if it was still possible to save the situation “before it reached the abyss.” Munich had “decimated” the opposition, Halder aptly commented.39

Perhaps even more important than the failure of the coup to get off the ground was the fact that the events of the last days of September destroyed the very premise on which the German opposition had based its strategy, and it is one of the curious aspects of the movement that this truth remained largely unnoticed. Despite all the uncertainties, no other attempt to strike Hitler down in these years would come close to having as good a chance of success. Thereafter the conspirators never ceased complaining about the “betrayal” of the Western powers, their feebleness and blindness. These oft-repeated reproaches surfaced just a few days after the Munich conference in a letter Goerdeler wrote to an American friend describing the accord as “outright capitulation” and predicting that war was now inevitable.40 Yet these statements actually illustrated the conspirators’ crucial strategic mistake, an error that was brought into stark relief by the debacle of September 28, 1938: they had made their actions dependent on events they could neither accurately foresee nor control-first, Hitler’s actually ordering an invasion; second, the Western powers’ then declaring war.

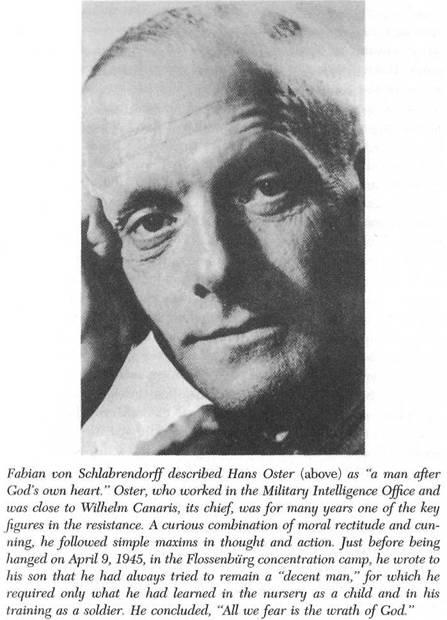

The conspirators would not overcome this basic flaw until shortly before July 20, 1944. Whereas in the fall of 1938 they made their coup contingent on Hitler’s going to war and on a firm response from Britain and France, they later made their activities dependent on Hitler’s victories and defeats: victories, they felt, made him popular with the people and therefore unassailable, while defeats laid them, his internal enemies, open to accusations of aiding and abetting the downfall of their own country. Most of the conspirators never escaped this dilemma, and the infirmity of purpose that is often imputed to the German resistance stemmed to a large extent from this self- imposed dependence on external circumstances. The alternative to this approach was embodied by Gisevius, the “eternal plotter,” as the other conspirators derisively called him. His radicalism, which so annoyed Halder, stemmed largely from his firm focus on the criminal nature of the Nazi regime. This enabled him to liberate action from all considerations of tactics, ultimate aims, and outside influences. Similar approaches were taken by Oster, Henning von Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht, Casar von Hofacker, and Carl Goerdeler, who had warned repeatedly against waiting for the “right psychological moment” and now considered emigrating to the United States.41

One evening soon after the debacle of September 28, Oster and Gisevius somberly burned the plans and notes for the coup-all that remained of their daring dream-in Witzleben’s fireplace. Many months would pass before the resistance began to recover from the blow it had suffered. Only a small, highly committed core of conspirators remained, and even they felt completely spent; their nerves were too frayed and their energy too depleted for them to organize another coup attempt, especially since to do so went against the grain of all they had been taught, their way of thinking and their traditions, which, though honorable, had been overtaken by the times. The industrialist Nikolaus von Halem, who maintained ties with a variety of opposition groups, had already dismissed the officers’ ideas as “romantic” in the summer of 1938 and observed that Hitler, the “messenger of chaos,” could only be removed from this world by a professional hit man, or at least some figure from the renegade old soldiers’ organizations. For a long time he considered attempting to persuade the former leader of the Oberland Freikorps, Beppo Romer, to undertake such an attempt.42

But Halem’s approach was ultimately just another brand of romanticism. Much closer to reality was Franz Halder, who steadfastly held to his highly negative view of the regime, refusing to allow himself to be seduced by any of Hitler’s triumphs and finding in the mounting horrors new confirmation of his belief that Hitler was evil incarnate. His willingness to take action flared up once again, but weakly and only for a passing moment For the rest of the time, he doggedly performed his duty, served his country, kept himself isolated, nursed his hatreds, and, despite the darkness and horror on all sides, would not be persuaded to act. At noon on September 28, when news of the Munich conference broke, he lost his composure after so many days of feverish preparation. According to one observer, he “utterly collapsed” on his desk, “weeping and saying that all was lost.”43