to be rid of these tasks. Keitel made notes in pencil on the Fuhrer’s further comments: Poland was not to be turned into some kind of “model province”; the emergence of a new “class of leaders” must be prevented; his policy required “a tough ethnic struggle, which could tolerate no constraints”; and “any tendency toward a normalization of conditions must be stopped.” Hitler concluded with his infamous remark about the “devil’s work” to be done in the East.21

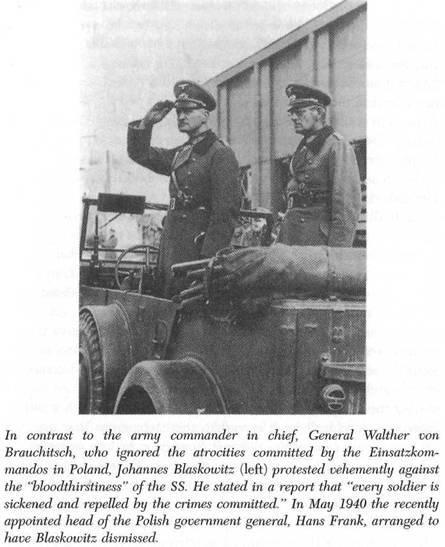

The abrupt end of the army’s responsibility for administration resulted in a surge of arbitrary actions on the part of party, civilian, and police authorities, kangaroo courts, district commissars, auxiliary police, and others, who could now claim to be carrying out special assignments not subject to external oversight. The change in administrative responsibilities also heightened the conflict with the army units remaining in these areas. General Karl von Rundstedt left his post as commander in chief of the eastern districts in horror after a short period; his successor, General Johannes Blaskowitz, sent Hitler a memorandum in early November describing the abuses, crimes, and atrocities, expressing his “utmost concern,” and pointing out the danger that these actions posed to the morale and discipline of the troops. Hitler rejected the “childishness” of the army command, saying, “You can’t wage war with Salvation Army methods.”22

Still the matter would not die. A little later Blaskowitz wrote to Brauchitsch of the “bloodthirstiness” of the Einsatzkommandos, claiming that it posed an “intolerable burden” for the troops and reiterating his demand that a “new order” be instituted soon. More important, officers who opposed the Nazi regime, Lieutenant Colonel Groscurth in particular, then distributed Blaskowitz’s memorandum to the commanders in chief of the western districts and their staffs, among whom it aroused “stupefaction” and “great agitation.” General Bock and others demanded to know whether “the hair-raising descriptions” were accurate and whether those responsible had been called to account. Some even demanded that a state of emergency be declared in the occupied territories.23

Although Brauchitsch shared the generals’ horror at what was happening, he once again stonewalled all requests to take; action. Finding himself increasingly besieged, he continued his hopeless attempts to allay the widespread outrage by downplaying events and refusing to discuss them. When this failed, he delegated responsibility for resolving discord to the lower ranks, where, as it happened, the opponents of the Nazi activities were winning converts to their cause. When, in January 1940, Blaskowitz arrived in Zossen with another, still more sharply worded memorandum stating that “The attitude of the army to the SS and the police alternates between abhorrence and hatred” and that “Every soldier feels sickened and repelled by the crimes committed in Poland by agents of the Reich and government representatives,” Brauchitsch flatly refused to forward it to Keitel or Hitler. General Ulex had no more success when he complained that SS and SD (Sicherheitsdienst, or Security Service) units demonstrated “an utterly incomprehensible lack of human and moral sensibilities” and had sunk “to the level of beasts.”24

Brauchitsch apparently never even passed along the concern, expressed by nearly all the critics, about the threat to discipline and the danger posed to supply lines by the prevailing state of pandemonium. He certainly never contemplated organizing a common protest or rallying the army commanders to resign en masse, though it seems likely they would all have agreed to this step, given that even an admirer of the regime like General Reichenau had on occasion expressed his revulsion at what was happening. By May, Hans Frank had been appointed governor general of the conquered territories, and he succeeded in having Blaskowitz replaced. Shortly beforehand Himmler had also succeeded, despite bitter opposition from both the OKW and the OKH, in obtaining permission to further expand the armed SS units and to form new ones. Despite its efforts, the Wehrmacht was never able to discover the troop strength of these units. It no longer played much of a role in the political calculations of the Nazi leadership.

It is not difficult in retrospect to identify when this decline began: during the Rohm affair years earlier. In a little-noticed directive from that period, the Ministry of Defense had ordered that people persecuted for political reasons should not be protected. It is arguable that this restriction so compromised the morale and self-confidence of the officer corps that decline was inevitable. In mid-January 1940 Halder noted in his diary a terse comment Canaris had made while visiting him. “Officers too faint-hearted,” Canaris had said, aptly summarizing the old-and now terrifyingly obvious-dilemma. “No humanitarian intervention on behalf of the unjustly persecuted.”25

The events in Poland belong to the history of the resistance because they illustrate the importance of basic moral standards and reveal the manner in which such standards were subordinated to the traditional virtues of the soldier. By this time, if not before, any ability to claim ignorance of the essential nature of the Nazi regime had evaporated for good. In fact, the activities in Poland of the state-sanctioned “murder squads,” as Henning von Tresckow called them, were a turning point for many, even if these people did not necessarily proceed to active resistance. There were of course many others, indeed a majority, especially among younger officers, who succumbed to “Hitler’s magic” in the wake of the overwhelming German victory and who viewed the failure of the Western powers to intervene, despite their declaration of war, as further evidence of the genius of the Fuhrer.26 Nevertheless, the hemorrhaging that the resistance had suffered between Munich and the outbreak of war was stanched, and the movement slowly began to recover. More important, opposition to the Nazis within the army was no longer based solely on Hitler’s foolhardy foreign policy and the military risks he ran but also on fundamental moral questions.

The precise role played by each of these various issues is difficult to determine, but they all came to the fore again in the protracted dispute between Hitler and the Wehrmacht after the Polish campaign, leading to a quick revival of the previous autumn’s plans to overthrow the regime. On September 12, when victory over Poland, though imminent, was still not complete, Hitler in his haste informed his chief Wehrmacht adjutant, Colonel Rudolf Schmundt, that he had decided lo launch an offensive in the West as soon as possible and certainly by late autumn. Eight days later the Fuhrer took Keitel into his confidence. On September 27, the very day that Warsaw capitulated, he finally summoned the commanders in chief of the three branches of the armed forces, informed them of his decision, and ordered them to begin working on plans for a western offensive. Once again he based his decision on the argument that because time was working against Germany, both politically and militarily, the offensive could not begin soon enough.

The army high command, in particular, was convinced that any attempt to “draw the French and English onto the battlefield and defeat them” within a few weeks, as Hitler had said, would be as hasty as it was hopeless. The entire corps of generals was incensed, and they deluged Brauchitsch with protests. On the basis of Hitler’s intimations that a settlement would be reached with the Western powers at the conclusion of the Polish campaign, the OKH had already begun to plan for redeployment in mid-September. It hoped that by simply mounting a solid defense against this enemy who had demonstrated so little stomach for war, it could gradually put the conflict “to sleep,” thereby clearing the way for a diplomatic agreement. Hitler reacted “bitterly” to these plans over the following weeks, partly because the commanders did not seem to share his elation over the victory in Poland but most importantly because their complaints during the campaign suggested that they still felt they had some right of consultation in political decisions, while he believed that this issue had been settled once and for all.27

Stung by Hitler’s response to them, the commanders retreated once again to purely military arguments. They pointed out that the troops were too tired to turn around and fight in the West, that stores of munitions and raw materials were depleted, that winter campaigns were always perilous, that the enemy was strong. But Hitler overrode all objections, regardless of source or context. When one general described the rigors of a late-autumn campaign, Hitler replied that the weather was the same for both sides. Even Brauchitsch objected openly to Hitler’s plans and asked Generals Reichenau and Rundstedt to speak to him. When this, too, failed, these political and military concerns, now sharpened by moral considerations, led to a revival of plots to stage a coup.

By the end of September Canaris had already visited the various western headquarters to explore the officers’ attitudes about the planned offensive and, in some cases, to gauge support for the overthrow of the regime. At the same time, Brauchitsch and Halder held an “in-depth conversation” about the choices they faced: either to stage the offensive that Hitler wanted or else to do everything possible to delay operations. A third eventuality was also raised in this conversation and duly noted in the official diary, namely to work for “fundamental change,” by which they meant nothing less than a coup.28

As might be expected, Brauchitsch shrank from such a radical solution and preferred instead to create