delays attributable to technical problems. Hitler, however, was in no mood for such ploys. He informed his commander in chief two days later that no hope remained of reaching a settlement with the Western powers and that he had made an “immutable decision” to wage war. The new campaign would be launched sometime between November 15 and 20. Five days later, on October 21, in a speech to the gauleiters, Hitler suggested an even earlier date, assuring them that the “major offensive in the West” would begin “in about two weeks.”29

Brauchitsch was in despair. Canaris, who visited him late in the evening, was “deeply shaken” by both the nervous exhaustion of the commander in chief and by his report, in which the words “frenzy of bloodletting” appeared for the second time in recent days, now applied to Hitler and his furious desire to attack.30 In the continued hope of forcing a postponement, Brauchitsch decided to work out only a sketchy campaign plan. But Hitler allowed him no leeway and only a few days later demanded the necessary amplifications, setting November 12 as the new date for the invasion. He ordered Generals Kluge, Bock, and Reichenau to Berlin to help speed up planning in the high command. All objections raised by the commanders, of whom Reichenau was characteristically the most outspoken, were dismissed by Hitler as unfounded. Once again he urged Brauchitsch and Halder to hurry and concluded by producing some new operational plans of his own.

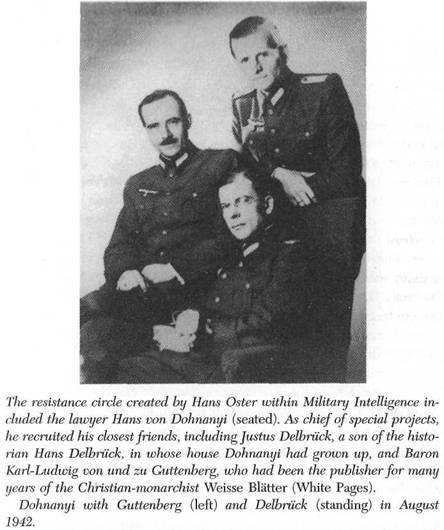

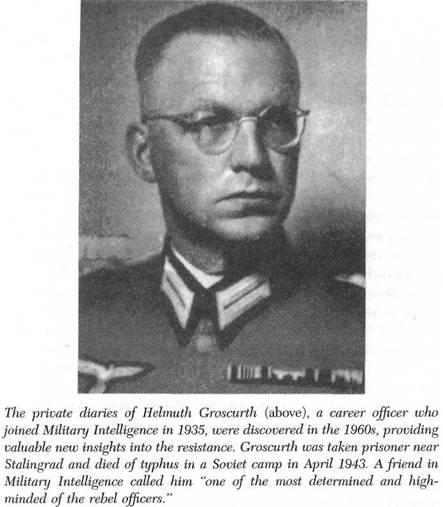

The increasing pressure exerted by the Fuhrer, coupled with his evident disdain for the military, prompted a group of younger general Staff officers to renew their old connections with opponents of the regime in the Foreign Office and, most important, in Military Intelligence, where Hans Oster had continued to work away with the en couragement of Canaris, who was now impatient to proceed. Oster had recruited Hans von Dohnanyi into Military Intelligence, and Dohnanyi in turn had brought in a number of close friends who opposed the Nazis, including his boyhood companion Justus Delbruck, baron of Guttenberg, and the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dohnanyi’s brother-in-law, who provided a bridge to Christian opposition circles. At the same time, Helmuth Groscurth resumed close contacts with Beck, who rekindled the connection to Goerdeler. Gradually, through many more intermediaries as well, various old and new contacts were established.

The resumption of ties to an active opposition group seemed to save Goerdeler from a psychological crisis. In his isolation he had fallen in with a group of staid old national-conservatives who did nothing but meet, talk, draft reports, hope, and wait. He had become increasingly distraught and had lost himself in far-fetched revolutionary schemes. Over Beck’s vehement opposition, he worked on the idea of asking Hitler to send him on a mission to Britain and France to discuss peace conditions that, he calculated, “Hitler would not swallow and that would then lead to his downfall.”31 Goerdeler originally envisaged a “transitional cabinet led by Goring” for the first weeks following Hitler’s fall. Other opponents of the Nazis advanced similarly misguided schemes, such as working with “open-minded circles” within the SS and tossing Ribbentrop “like a bone” to the enemy.32 They argued for hours over the restoration of the monarchy and who would be the best pretender to the throne. These ludicrous fantasies stemmed, for the most part, from an enervating lack of real activity. If it is true that absolute power corrupts absolutely, and with respect to Hitler’s regime that is irrefutable, then absolute impotence has a similar effect, at least insofar as any sense of reality is concerned.

To the great disappointment of all the plotters, Halder continued to insist in the last days of October that the time was not ripe. Even the far more decisive General Carl-Heinrich von Stulpnagel now accused Oster and Canaris of rushing things. Neither Halder nor Stulpnagel apparently knew anything about the resistance cell within the high command called Action Group Zossen, which had been formed in midmonth primarily by younger staff officers in Colonel Wagner’s circle. This ignorance throws a telling light on the isolation of the opposition groups and the lack of coordination among them. More radical and concrete in its approach than other conspiratorial circles, Action Group Zossen had formulated plans for eradicating Hitler, eliminating the SS and Gestapo, cordoning off the main centers of power, and even forming a provisional government.

Appeals for action now rained down from all sides. In order to prompt the indecisive Halder and, even more important, Brauchitsch to make their move, the conspirators in Military Intelligence wrote a paper, with the help of Secretary of State Ernst von Weizsacker in the Foreign Office, Erich Kordt, and Hasso von Etzdorf, in which they once again marshaled the arguments against the planned western offensive. In their view, Hitler’s plans would bring about “the end of Germany,” a belief confirmed by his announcement that he intended to invade through Belgium and Holland, thereby in all likelihood drawing the United States and numerous other neutral countries into the fray. Experience, they continued, showed that protests and threats to resign would not change Hitler’s mind and would only confirm his conviction that all “ships must be destroyed and bridges burned.”33

Finally, after long hesitation, worn out by his exertions and by Hitler’s scornful impatience, Halder decided on the last day of October 1939 that action could no longer be delayed. The mounting concern among the generals, as well as the pressure from Etzdorf, the Foreign Office, and Action Group Zossen, may have helped convince him there was once again hope that a coup would succeed. In any case, he summoned Groscurth on the evening of October 31 and informed the surprised Military Intelligence officer that he, too, had finally concluded that violence was the only solution. Halder mentioned his earlier plan of eliminating at least some of the leading Nazis in a staged accident. He outlined a few details concerning the operation itself and the new regime to take power afterwards and then added, with tears welling up in his eyes, that “for weeks on end he had been going to see Emil [Hitler] with a pistol in his pocket in order to gun him down,” as Groscurth recorded in his coded diary.34

As often happened when a decision was finally made, support arrived from unexpected quarters. Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, the commander of Army Group C, sent Brauchitsch a letter that ended with the comment that he was prepared “personally to stand fully behind you and to support whatever conclusions you reach or actions you deem necessary.” Oster and Erich Kordt had spent the evening of October 31 visiting Ludwig Beck on Goethestrasse in Lichterfelde. After much debate over the attitude of the generals, they arrived at the same desperate conclusion on which all their discussions had foundered for months: the most important condition for a successful coup was to kill Hitler. The next morning, when Kordt arrived al Military Intelligence, Oster half- resignedly summarized their discussion with the comment that no one could be found “who will throw the bomb and liberate our generals from their scruples.” Kordt told Oster simply and calmly that he had come to request permission to do just that. All he lacked was the explosives. After a few more questions, Oster promised to have the necessary materials ready on November 11.35

Everything was now rushing toward a final resolution. The very next day, when Brauchitsch and Halder visited the commanders in the West to canvass their views once again on the impending offensive, Stulpnagel invited Groscurth to come along and assigned him the task of “starting the preparations.” He offered encouragement and concrete information, especially about the position of reliable units and the commanders who could be counted on, and asked that Beck and Goerdeler be informed. Beck himself was discussing with Wilhelm Leuschner, a former trade union leader, the possibility of a general strike. A day later Oster was summoned to Zossen and asked to get out the previous year’s plans and update them if necessary. In his diary Gisevius captured the feeling of hectic excitement that filled him and the other conspirators, who had known nothing until then: “It’s going ahead… . Great activity. One discussion after another. Suddenly it’s just as it was right before Munich, 1938. I rush back and forth between OKW, police headquarters, the Interior Ministry, Beck, Goerdeler, Schacht, Helldorf, Nebe, and many others.”36 Meanwhile, in Zossen, arrangements were made “to secure head quarters.”

Once again everything was ready. Much as the coup a year earlier was to be sparked by the order to attack Czechoslovakia, this time everything would be set in motion by Hitler’s command to attack in the West. Since Hitler had set November 12 as the date of the offensive, the orders would have to be issued by November 5 at the latest. On that date Brauchitsch had an appointment to see Hitler in the Chancellery; he intended to make one final attempt to dissuade the Fuhrer from this “mad attack” by underscoring the unanimous opposition of the generals. Halder’s plans were based on the expectation that when the commander in chief returned from his meeting at the Chancellery, rebuffed and quite possibly humiliated as well, he would not hesitate, as he had in 1938, to issue the marching orders, which only he could sign.

At noon on the appointed day, while Halder waited in the antechamber, Brauchitsch began his presentation to Hitler in the conference room of the Chancellery. Although the commander in chief formulated his concerns more pointedly than originally planned, Hitler listened quietly at first. However, when Brauchitsch began arguing