straightforward kind of man who had very little or nothing about him that was somber, unresolved, or enigmatic. He therefore assumed that his fellow human beings needed only enlightenment and well-meaning moral instruction to overcome the error of their ways… . The eerie tangle of good and evil, the seductive ambivalence of certain kinds of mental gifts, the power of unacknowledged prejudices and secret desires, the entire shadowy area in which the inner lives of so many are played out-there was no room for any of this in his view of humanity.”11

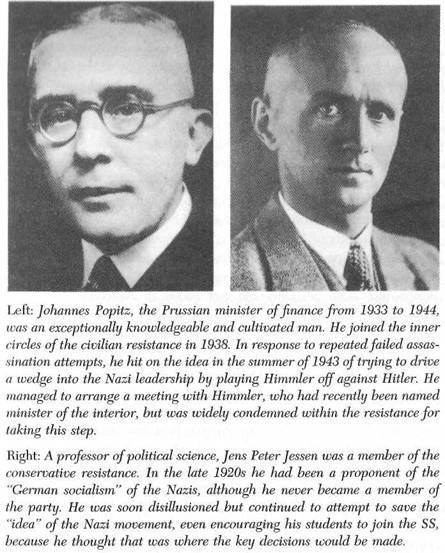

Even before the victory over France, Goerdeler had quickly turned out a series of memoranda for his colleagues from which he then distilled a coherent overview of the positive aims of the resistance. The outline of the new order that resulted from this effort, entitled “The Aims,” was finished in early 1941 and reflected not only his own ideas but, even more important, those that emerged in the course of comprehensive discussions with Beck; Johannes Popitz, the Prussian minister of finance; former trade union leaders such as Wilhelm Leuschner and Jakob Kaiser; and many others. Later Goerdeler also drew on a group of Freiburg professors, including Walter Eucken, Constantin von Dietze, and Adolf Lampe, the founders of the social market economy, as well as historian Gerhard Ritter and others, who had come together out of disgust for the regime after

Despite their clashing views, however, all the opposition groups, the conservative “notables” to the various left-wing factions, were indelibly marked by their common experience of the totalitarian dictatorship that erupted in the midst of the democracy of Weimar and by the inability of the political parties, whether on the left or the right, to deal with this disaster. Virtually all opposition circles tended to blame this breakdown on the unyielding antagonism among the parties, which was played out in terms of nineteenth-century slogans and popular platitudes that no longer bore a resemblance to reality. The opponents of the Nazis turned their attention to the structures that had encouraged this disunity. Sweeping critiques of modern civilization had long been fashionable in Germany, and they certainly played a role as well, with their indictments of “mass society,” “urbanization,” the original sin of “secularization,” and the spreading “materialism” that undermined all sense of higher purpose. The fact that even Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who certainly did not move in conservative circles, spoke of a “trend toward mob tastes at all social levels” demonstrates the prevalence of the aversion to modernity implicit in these critiques.13 Like most other people of his political persuasion, he interpreted National Socialism as an expression, albeit an extreme one, of such modernist tendencies.

Virtually all the internal opponents of Nazism believed that it had originated in the miseries of the Weimar Republic. Even former supporters of democracy were convinced that Germany must dispense with political systems based on parties and adopt instead a rigidly structured, if not authoritarian regime. In their search for a minimal political and moral consensus, without which they believed no state could survive, they frequently flirted with Utopian, “conflict-free” notions that were disturbingly reminiscent of the Nazis’ own ideology of a “people’s community.” Yet wherever their ideas led them, the members of these civilian opposition groups were united in their desire to bring the Nazi tyranny to a quick end and to reorganize social and political life from top to bottom.

Much criticism has been directed at the German resistance’s persistent skepticism toward democracy, its desire to return to older ethical systems and human values that were eternally valid and only in need of a contemporary form of expression. Hannah Arendt, for instance, saw the German resistance as nothing more than a continuation of the antidemocratic opposition to the Weimar Republic. After the collapse of the republic, which was, she stated, partially brought on by their efforts, resistance leaders paradoxically invoked Hitler as well, in order to advance what Arendt viewed as their own reactionary objectives. Others have seen a connection between the resistance and the so-called conservative revolution, that restless movement of radical intellectuals from all sides of society who were united only in their distaste for the democratic order.14

It is true that resistance groups of all kinds, and not just national conservatives, considered the “Weimar experiment” a hopeless failure and basically differed only in the conclusions they drew from it. Significantly, there was not a single well-known proponent of the defunct republic in these various circles despite the profusion of views their members held.15 It would be historically inaccurate to pin the resistance down to this initial position. Close examination reveals numerous conflicts, some of them never resolved, and continuous confrontations that led to fresh insights. The resistance was neither static nor monolithic. Its peculiarity and perhaps even its glory lay in the openness and intellectual ferment it created as its members moved, often with much soul searching, from their original views, which tended to be narrow and highly conditioned by a particular social and political background, to broader visions.

Carl Goerdeler himself can be taken to illustrate this phenomenon. There is every reason to believe that he was closely involved in the draft constitution put forward by Ulrich von Hassell and Johannes Popitz, both senior officials in earlier governments, in early 1940. Under this plan, a three-person council would assume executive power after the Nazi dictatorship had been overthrown, with Beck as its leader, and a constitutional council would be formed to restore “the majesty of the law.” Although the draft constitution clearly stated that this regime, quasi-dictatorial at best, would only be temporary, no termination date was specified and no mention was made of elections.

Goerdeler’s counterproposal illustrated his unmitigated but perhaps misguided faith in reason, he suggested holding a plebiscite us soon as possible so as to give the new regime a solid popular base. His friends firmly rejected this proposal on the grounds that the corrupting effects of the Hitler years would still be felt for a considerable period so that it would be foolish to submit the new order to the peoples will too hastily. Once again, however, Goerdeler was dissuaded from an authoritarian approach by his stubborn belief in the good judgment of humankind. He continued to insist, despite well-founded doubts on all sides, that if the truth about the Nazis could be freely spoken for “only twenty-four hours” their myopic followers would suddenly see the light. The same kind of reasoning led Goerdeler to argue that the NSDAP should not be prohibited under the new order.

Differences of opinion about the transitional regime remained. The political scientist Jens Peter Jessen and the lawyer Carl Langbehn, who advised the conspirators on their plans, added a sharply worded clause to the draft providing for a time limit on the state of emergency. The conspirators generally agreed, however, that all criminal acts committed under the Nazi regime should be severely punished: the “sword of justice,” as Goerdeler later wrote, adding to the typical bombast of the times his own touch of the country pastor, must “mercilessly strike down those who have corrupted the fatherland into a caricature of a nation.” Mere membership in Nazi organizations would not be punishable under this plan, though, and anonymous denunciations would be inadmissible in court. The conspirators also planned a law to rectify past injustices, especially toward Jews. A dubious feature of this law, however, was a set of provisions that recognized the citizenship of Jews whose families had long been established in Germany but that called for every effort to be made to enable more-recent Jewish immigrants “to found a state of their own.”

The modifications that the conspirators’ thinking underwent over the years is also evidenced in the fate of a plan Goerdeler and some of his advisers originally advanced to restore the monarchy. They were by no means royalists; rather, their intent was to establish an institution that would be universally accepted and remain above the fray of daily political life as the British and Dutch monarchies were. It seems that tactical considerations also played a role in their proposal: the conspirators hoped thereby to win the support of conservatives, especially within the officer corps. In the course of many lengthy debates, various names were considered as possible pretenders to the throne, but in the end the entire subject was dropped when it met with passionate opposition from Helmuth von Moltke’s Kreisau Circle.

Many variants of Goerdeler’s constitutional plans have survived, indicating both his openness to new ideas and the influence of changing advisers. But the core of his plan, which eventually took shape after a rather nebulous start, was always a strong government in which various “corporatist bodies” played a leading role while the parliament was limited to a more or less supervisory function. This basic thrust found expression in a