Circle as little more than idealistic or eccentric fantasies. They had grown up at time when Germany was rising into the ranks of the great powers of the world and to them concepts as nation-states, great-power status, zones of influence, and national interest were like the laws of physics-they could not simply be abolished. Virtually all the members of the Goerdeler group thought that at least the “greater German territories” should remain within the Reich. This has given rise to accusations that there were strong underlying similarities with the regime-or even that the national-conservative opposition was simply striving to realize Hitler’s aims without Hitler.

As far as the first revisionist interpretation is concerned, there is some truth to this accusation. When Hitler pointed time and again to the injustices of the Treaty of Versailles as the grounds for his demands, people like Beck, Goerdeler, and Hassell could only nod in agreement, all the more so as his arguments were widely shared abroad, especially in Britain. Those who most strenuously indict the Goerdeler group, however, ignore an essential distinction: although the national conservatives generally agreed with Hitler’s border claims, they did not agree with his methods. Ludwig Beck, for instance, said as early as 1938 that war was not only militarily absurd but anachronistic, and he attempted to resist, though perhaps not forcefully enough. At about the same time, Goerdeler called Hitler a “national bandit” for risking Germany’s honor and reputation on one adventure after another.25

The inconsistencies within the conservative position therefore became all the more apparent with the outbreak of the war. Although Goerdeler repeatedly called for peaceful cooperation in Europe after Hitler and a renewal of the League of Nations, the papers he wrote after the conquest of France spoke unabashedly of “German leadership” on the continent. Among other contradictory positions, he assured the Western powers that Poland would be restored but he insisted on Germany’s eastern frontiers of 1914. Hermann Graml has demonstrated convincingly that the “notables” clung to the familiar. They could only imagine, for instance, a unification of Europe and a distribution of power that would resemble the unification of Germany under Prussia.26

The conservatives’ reflexive belief in the concept of the great powers, so deeply rooted in their psyches, began to disappear, however, by the end of 1941-and not just because of the spread of the war to the Soviet Union and the entry soon thereafter of the United States. More important was the mounting awareness of the destruction wrought by arbitrary German policies in southeastern Europe after the Reich smashed Czechoslovakia and extended its dominance deep into the Balkans. Most important of all were the rampant reports of massive crimes in the East, which cast a pall over all talk of the “Reich’s mission to bring order and peace.”

Despite the persistent disagreements between the two main civilian opposition groups, contacts were gradually established. Ulrich von Hassell played an especially important role in this regard. Although he was always uneasy with the utopianism of the Kreisau Circle, he shared many of its objections to Goerdeler and believed that the two most important resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger. The rest of the work necessary for a rapprochement was accomplished thanks to his skill as a negotiator. There were also contacts between Yorck and Jessen, Schulenburg and Goerdeler, and Popitz and Gerstenmaier. After strained preliminary negotiations, the two groups met for the first time on January 8, 1943, in Yorck’s house, with Beck serving as chairman. They made little progress in narrowing the differences between them, partly because Goerdeler “trivialized all attempts to get to the heart of matters,” as Moltke noted with great exasperation. But in the end a majority of the Kreisau group supported the selection of Goerdeler as chancellor of a transitional government, despite some complaints that the decision represented a dangerous “Kerensky solution.”27

Now, under the influence of the Kreisau Circle, the national-conservative resistance moved even more quickly to drop its insistence that Germany play a leadership role in the new Europe. By mid-1943 Goerdeler himself had discarded a number of hitherto cherished notions. With all the impulsive exuberance of his nature, he began to speak of a European “peace confederacy” that no nation would dominate and in which “inner-European borders” would play “an ever-diminishing role.”

Similarly, the ideas of the Kreisau group were colored by its increasingly close contacts with the Goerdeler people. There is no convincing evidence, however, for the accusation raised from time to time that the Kreisauers became infected with old nationalist ideas. It is true that Adam von Trott began insisting somewhat more deter minedly on a “reasonable peace plan” for post-Hitler Germany and warning against the ruinous consequences of a second Versailles. But an unbiased observer would have to acknowledge that both the Kreisau Circle and the Goerdeler group, as well as Oster, Leber, Gisevius, and many other opponents of the regime, rejected nationalism much more strongly than most of their contemporaries did, even if they were less than sure-footed as they ventured onto new terrain.

The progress they had made is evident when considered in the light of the fruitless efforts of the German resistance over the years to establish contacts with like-minded people in other countries through the World Council of Churches, Allen W. Dulles, head of the Office of Strategic Services in Bern, the lawyer Eduard Waetjen, Theodor Strunk, Ulrich von Hassell, Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz, and numerous others. Most of the politicians and military leaders whom they unsuccessfully courted in London, The Hague, and Washington still believed, however, that these Germans were committing “treason” and therefore regarded them with contempt. There was no appreciation of the fact that the opponents of the Nazi regime felt guided by new principles and laws whose legitimacy did not end at national borders. Even after the failed coup attempt of July 20, 1944, the

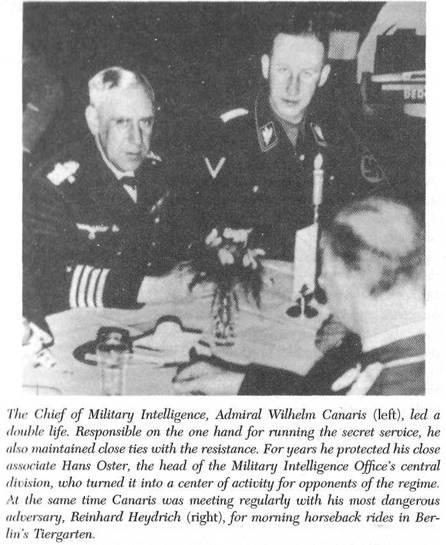

Out of the blue during the summer of 1941, alarm bells sounded at Military Intelligence, when the commotion attending the victory over France and Hitler’s celebration of himself as the “greatest general of all time” had not yet died down. The research office informed Canaris that the timing of the western offensive had probably been betrayed by a German officer. The monitoring service had taped Colonel Sas’s telephone conversation with The Hague on the eve of the attack and decoded telegrams from Belgian ambassador Adrien Nieuwenhuys, in which he mentioned an informant in Rome. Suspicion immediately fell on Josef Muller, whom Military Intelligence had sent to the Vatican, and then on Hans Oster himself.

In fact, it is remarkable that the constant bustle surrounding Oster and the other conspirators, their trips and often frantic telephone calls, as well as their unannounced visits and swiftly closed doors, could have failed to attract attention for so long in as highly organized a police state. Virtually none of the conspirators lived in a world of his own. Most worked in government departments where everyone was acutely aware of everyone else and where personal animosities and rivalries, ideological conflicts, and competition for positions abounded. Everyone in Military Intelligence would presumably have been aware of Oster’s friendship with Sas and his continuing contacts with Beck, Goerdeler, Popitz, Kordt, and others. Oster once gestured toward the five telephones on his desk and commented to a visitor, “That’s me. I’m the middleman for everything.”29 In his diary Hassell recorded numerous breakfast meetings in hotels with four or more people, as well as “gentlemen’s evenings” and walks in the Tiergarten. Occasionally he remarked on having all met at Beck’s apartment or Popitz’s or Jessen’s- and then gone together to Yorck’s place. Most of the conspirators demonstrated a similar lack of caution for years on end and were quite careless about whom they revealed their plans to. The likeliest explanation for why they were not apprehended sooner is that the military and the civil service, having fallen quickly into line after 1933, were not regarded with much suspicion by the security apparatus, whose gaze was still focused on the Nazis’ original foes- Communists, Social Democrats, labor union leaders, and church figures suspected of opposing the regime.

Canaris seemed to be deeply upset by the rising tide of evidence against Oster. Those who knew the admiral found him an enigmatic, inscrutable personality, who always maintained a certain distance from people as well as from his duties. Among all the competing elements of his nature there may even have been some part that could understand the treason of his closest collaborator, though there is no evidence of this. In any case, Canaris continued to protect both Oster and Muller despite the fact that Hitler himself had taken an interest in the issue and had ordered Canaris to join Heydrich in conducting the investigation. Canaris demonstrated great resilience and flexibility in drawing the inquiry into his own hands, leading it, and then letting it drop quietly, all at great personal