considerable expansion of self-government at even the lowest levels of society; not only municipalities but universities, student bodies, churches, and professional organizations would be involved. To the end of his life, Goerdeler clung to the belief that this was the genuine “German way” in politics, which had proved itself even amid the confusion of the Weimar years and despite “extreme democratization” and “extensive corrosion by political parties.” The various states within Germany he reduced to little more than large administrative units, seeing them as an intermediate level of government that was not really close to everyday life and yet too far removed from the focus of real power.

In the same spirit, Goerdeler attempted to limit the influence of the general public, especially through political parties, and to turn the decision-making process over to indirectly elected bodies whenever possible. One of the clear contradictions between Goerdeler’s theory and his practice was that, despite his belief in the power of reason, he never entirely freed himself from the fear he had acquired in the Weimar years of what ordinary people might do. Notions such as “the power of parties,” “splinter parties,” and “self-interested parties” continued to haunt his own constitutional thinking as well as that of the entire group.

The election process was therefore calculated to bring forth strong, experienced “personalities with roots in real life” by means of a complicated modified majority-rule system. It is noteworthy that all the opposition groups agreed on this, despite their strong differences on other questions. The socialist Carlo Mierendorff said “never again shall the German people lose their way amid the squabbling of political parties,” and his fellow socialist Julius Leber called for an end “to the old forms of party rule.” It was he who summarized as follows the argument against proportional representation, which he blamed most of all for creating political fragmentation: “It fails totally to carry out its real functions, namely, selecting suitable men and maintaining the trust between the people and the leadership. Instead, it simply imposes on politics the determined dullards who eventually rise to the top of party hierarchies.”16 Goerdeler even contemplated a drastic limitation on majority rule by restricting seats in the parliament to the three strongest parties.

Another suggestion for the new order would have conferred a double role on fathers with at least three children. Other plans for reform reflected the strong corporatist tradition in German society. Goerdeler, for instance, wanted to see a

Goerdeler also advanced some suggestions about how the economy should operate: he advocated moderate liberalism, limits on the role of industry (a stricture that clearly reflected the influence of the Freiburg school), participation of workers in corporate management, and a sense of social responsibility on the part of the propertied classes. There were many thoroughly antimodern aspects to Goerdeler’s proposals, which were as passionately opposed to the egalitarian tendencies of contemporary industrial societies as they were to pluralistic social and political interests. Goerdeler wanted to bring all these contending interests together within an idyllic, community-based order that served the general interest. Thus there was a definite Utopian cast to national- conservative thought, an inclination to idealize the “good old days” even though, as everyone knows, they were never all that good. Nevertheless, these efforts cannot be dismissed as mere attempts to restore the lost societies of the past. Goerdeler’s close working relationship and even friendship with trade union leaders such as Wilhelm Leuschner and Jakob Kaiser points to the contrary. Indeed, the first people to accuse Goerdeler of being “reactionary” were, in a remarkable twist, the most conservative members of the group-Hassell, Jessen, and Popitz-who denounced Goerdeler’s proposals for going too far toward restoring democratic “Weimar” conditions.17

These proposals, of course, were fragmentary. Many of them were inevitably driven by tactical considerations, and in any case, there is always a great divide in politics between theory and practice. It is impossible to say whether Goerdeler’s proposals would have been adopted if a coup had succeeded. Thus they are primarily of interest for what they reveal about the two primary goals of Goerdeler’s group, namely the far- reaching depoliticization of government and the overcoming of political fragmentation by forging a new sense of community. The Weimar Republic cast as long a shadow over these objectives as it did over the Hitler years. An underlying feeling of helplessness pervades these proposals. When Goerdeler remarked that he wanted to pursue the “German way” in drafting his constitution and would not allow himself to be “led astray” by Western models, he inadvertently disclosed an intellectual detachment and isolation that the entire German resistance never overcame. In the end, however, Goerdeler was not motivated by the desire for social and constitutional change embodied in these proposals, nor did he justify himself by them. They were produced under great pressure and emotional stress and were often not fully developed. To understand Goerdeler we have to look to more compelling forces.18

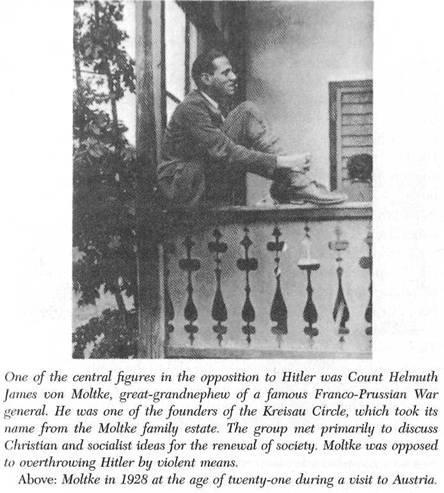

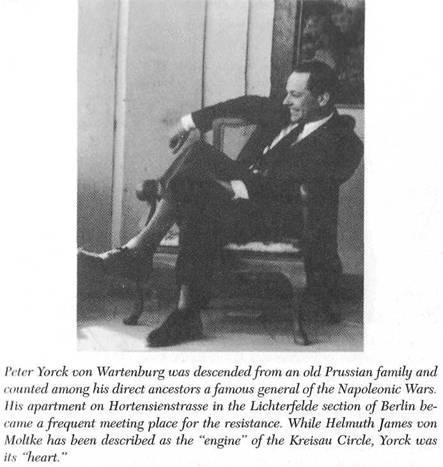

Quite different from the Beck-Goerdeler-Popitz group, and yet in some ways strangely similar, was the other important group of civilian opponents of the Nazi regime. It was founded and held together by Helmuth von Moltke, a great-grandnephew of the celebrated army commander of the Franco-Prussian War, who worked in the Wehrmacht high command as an expert in international law. His group was later dubbed the Kreisau Circle after the estate owned by the Moltke family in Silesia, although it met there only two or three times. Its intense discussions, conducted in working groups, took place more frequently in various locations in Berlin; beginning in early 1943 most were held on Hortensienstrasse in Lichterfelde, at the home of Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, another bearer of a famous name in Prussian history. Related to both Moltke and Stauffenberg, he was a lawyer and officer who had been assigned to the eastern department of the Defense Economy Office. While Moltke has been described as the “engine” of the group, Yorck von Wartenburg was its “heart.”19

Around Moltke and Yorck gathered what at first glance appeared to be a motley array of strong-willed individuals with markedly different origins, temperaments, and convictions. Among them was Adam von Trott zu Solz, a descendant, on his mother’s side, of John Jay, the first chief justice of the United States. Trott had been a Rhodes scholar and had many friends in England, including the so-called Cliveden set around David Astor. Like Hans-Bernd von Haeften, another member of the circle, Trott was employed in the Foreign Office. Striving to include experts from as many areas of political and social life as possible, the Kreisau Circle recruited Horst von Einsiedel, a Harvard graduate and an expert in economics. Carl Dietrich von Trotha, on the other hand, was a cousin of Moltke’s, born in Kreisau, and had been, like some other members of the group, a student of the philosopher and sociologist Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy.

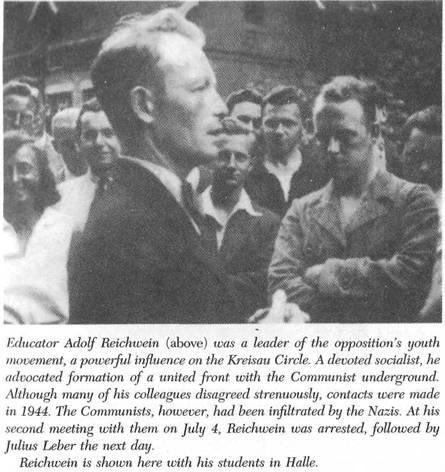

The most striking characteristic of this group, apart from its strong religious leanings, was its earnest and quite successful attempt to attract a number of devoted but undogmatic socialists. Among them was the educator Adolf Reichwein, who came from the Romanticist youth movement of the 1920s and had met Einsiedel and Moltke in one of the reform-minded volunteer work camps. Through Reichwein, Theodor Haubach also joined the group. A former student of Karl Jaspers and Alfred Weber, Haubach was nicknamed The General by his friends because of his expertise in military policy. He also had a deep interest in philosophy and the arts and had served as chief press officer of the Prussian government for several years.

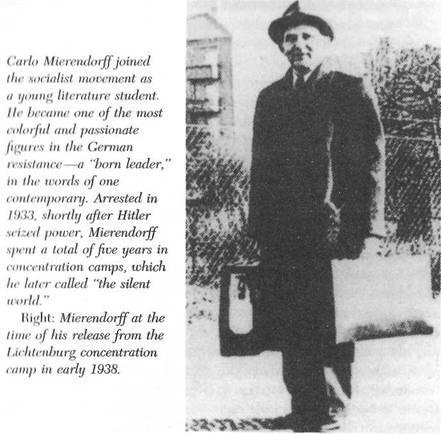

Haubach, in turn, recruited the man who was possibly the most colorful, emotional, and powerful figure in the circle, Carlo Mierendorff, a close friend since their school days in Darmstadt. Like Haubach, Mierendorff had a background in literature; before finally devoting himself entirely to politics, he had dabbled in the expressionist movement and edited a magazine. According to another acquaintance, the writer Gerhart Hauptmann, he was a “born leader.” Within the Social Democratic Party he was one of the young rebels who look on the complacent party hierarchy and its outdated programs and slogans. Mierendorff was arrested shortly after Hitler took power and spent five years in concentration camps, where at one point he was delivered by camp authorities into the hands of Communist fellow prisoners, who beat him nearly to death. During this time Haubach sought constantly to obtain the release of his friend, succeeding even in reaching Adolf Eichmann. (Never, he later said of Eichmann, had he seen “such glassy green eyes.”20)

A number of figures from the Christian resistance also joined the Kreisau Circle, including the Jesuits Alfred