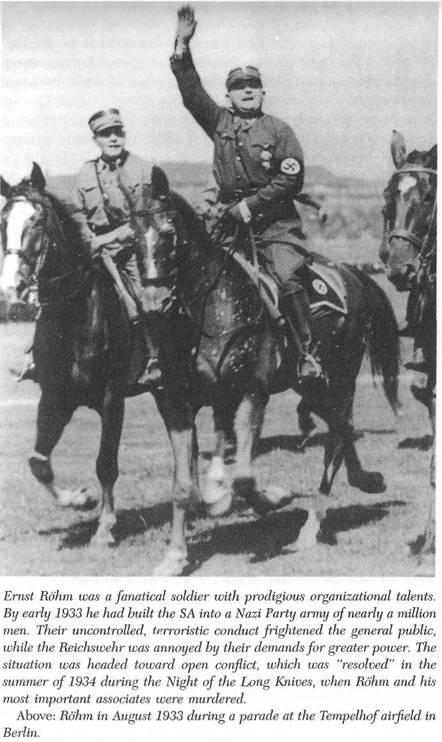

terror in the streets, to open up its own “wildcat” concentration camps, and to disrupt trials and legal proceedings-occasionally going so far as to beat up fellow party members who showed too much restraint- Rohm reminded his followers with mounting anger of the sacrifices they had made and the dead they mourned. When his demands on the government went unheeded, he found himself increasingly driven lo take the stance of the betrayed revolutionary.

Bitterly disappointed by the course of events and spurred by the agitated masses, who were eager for the spoils of victory, he whipped up his followers in the SA with speeches and harangues, insisting that “the national revolution must end now and become a National Socialist revolution.” Talk began to circulate in SA circles of the need for a “second revolution” to boost the Nazi movement fully into the saddle, to free it from its wretched mire of half measures, and to sweep Rohm and his organization to the top. When Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick warned in the summer of 1933 that he would take “severe measures”—at the very least putting disorderly SA members in “protective custody”—and followed through by clamping down on SA activities, Rohm threatened to march two brigades up to Frick’s headquarters in the Vossstrasse and give him a public whipping.8

But Rohm did not confine himself to making extravagant remarks before cheering supporters. His slogans promising a “second revolution” were aimed first and foremost at the Reichswehr, which had so far successfully resisted

The generals of the Reichswehr were understandably protective of its traditions and prerogatives; Rohm’s increasingly urgent and imperious designs alarmed them and confirmed their worst fears. As if to bring matters to a head, in the fall of 1933 Rohm incorporated another right-wing paramilitary organization into the SA, the Stahlhelm (“steel helmet”), which had originally been founded as a First World War veterans’ group. At a single stroke he raised the strength of his domestic army to nearly three million men. At the same time he began building the SA into a state within the state, enhancing its military aura, creating a network of offices to oversee a little of everything-including paramilitary sports, gymnastics, and life in the universities-setting up an SA police force and judicial system, and establishing liaisons to industry, government, and the press. Despite his strident, relentless insistence on the unsatisfied demands of his followers, Rohm continued to have confidence in Hitler and considered him merely indecisive and susceptible to “stupid and dangerous” characters like Goring, Goebbels, Himmler, and Hess, who were blocking the way to the real revolution and the dawn of an SA state.10

Hitler probably basically agreed with Rohm’s ideas. The Fuhrer certainly shared his distaste for the officer caste, with its monocles and starchy mannerisms. If Hitler had exhibited any support for Rohm’s demands at this juncture, however, he would have not only aroused the animosity of the Reichswehr and President Hindenburg but also jeopardized his alliance with the conservatives, undermined his basic tactic of “legal revolution,” endangered the incipient economic recovery, and possibly even invited intervention by foreign powers. In short, supporting Rohm would have sabotaged his entire strategy for seizing power. At least for the moment, Hitler remained reliant on the expertise of the senior Reichswehr officers as he set about the pressing military tasks he had designated for himself, above all the rebuilding of the army.

Nevertheless, Hitler did not want to dismiss Rohm’s demands out of hand. He even quietly encouraged the SA leader on the theory that all obstacles put in the path of the Reichswehr would ultimately make it more amenable to his will. At a conference of army commanders in December, Blomberg expressed great concern about “attempts within the SA to establish an army of its own.” Six weeks later he received a memorandum from Rohm in which the SA chief flatly declared “the entire realm of national defense falls within the purview of the SA.” The next day, as if not wishing to leave the slightest doubt about his plans, Rohm added comments that the generals took as an open declaration of war: “I now consider the Reichswehr to be only a military training school for the German people. The conduct of war and therefore also the mobilization [of troops] are henceforth the concerns of the SA.”11

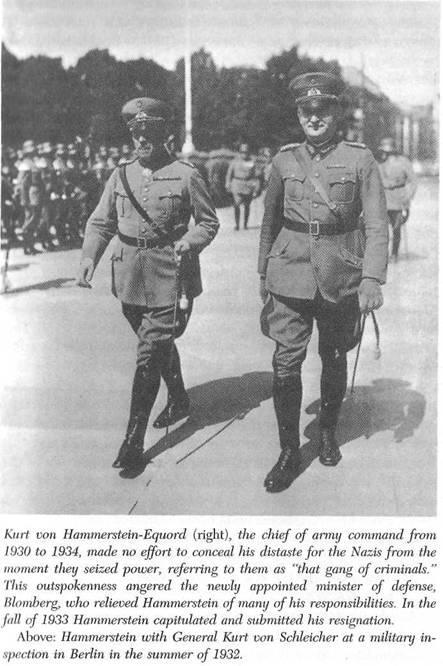

Blomberg and Reichenau responded by insisting on “a clear decision.” Just as Hitler had expected, they made numerous attempts at accommodation to curry favor with him. A preliminary concession had already been made. The commander in chief of the army, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, was an aloof, sarcastic man, who punctuated his principles with cutting displays of disregard.12 He made no secret of his aversion to the new rulers, even speaking of them in wider circles as “that gang of criminals” or “those filthy pigs,” the latter an allusion to the homosexual tendencies of the SA leaders. As a result, more and more of Hammerstein’s responsibilities were assumed by Blomberg, for whom the duties came more easily than for Hammerstein, who had neither talent nor desire for intrigue and insisted on straight dealings. By the spring of 1933 it was already being rumored that the commander in chief of the army would last, at most, until the summer. Though somewhat passive, Hammerstein ultimately held on until the fall before submitting his resignation. Within the officer corps, hardly an eyebrow was raised. Things finally seemed to be improving, and “everyone was happy to be rid of Hammerstein.”13 Blomberg even went so far as to order his department head in the ministry to forbid any further contacts with the former army commander in chief.

This initial attempt to appease Hitler was soon followed by a second. Just a few days after the commanders’ conference in early February, Blomberg ordered that Nazi insignia henceforth be the official symbol of the armed forces. Somewhat later he mandated that the officer corps adopt the so-called Aryan paragraph of the Act to Re store a Professional Public Service of April 7, 1933, requiring, among other things, that civil servants of non-Aryan descent be retired.14 Shortly thereafter Blomberg issued orders making “sympathy with the new state” the decisive criterion for promotions and, still at his own initiative, introduced a program of “political training” for soldiers. Hitler, who was well versed in reading omens, may have viewed these gestures as the first sign of impending capitulation, despite all the grumbling about them in the Reichswehr.

To entice the army further down this path Hitler himself offered a concession: at the army’s Bendlerstrasse headquarters on February 28, 1934, Rohm was forced to sign a paper in Hitler’s presence that confirmed all the prerogatives of the Reichswehr and delegated only supporting military-training duties to the SA. The dispute between the two military forces was then officially washed away in a “reconciliatory breakfast,” at which, according to Blomberg, the Fuhrer delivered a “stirring” appeal to keep the peace.

Hardly had the ceremony ended, the table been cleared, and the guests departed, however, before Rohm exploded in a tirade of rage and frustration. He called Hitler a “ridiculous corporal,” accused him of disloyalty and shouted, “If it can’t be done with Hitler, we’ll do it without him!” One of the witnesses, SA leader Viktor Lutze, scurried away from the champagne breakfast in the Huldschinsky Palace, Rohm’s headquarters in Berlin, to Hitler’s camp at Berchtesgaden to report what had happened. The Fuhrer curtly informed him, “We’ll just let this ripen.”15

In the meantime Rohm carried on as if the agreements, assurances, and solemn handshakes of February 28 had never occurred. He purchased arms abroad, displayed SA muscle in gigantic military parades, held public flag-consecration ceremonies and reviews of his troops, and rode, mounted high on his steed, before the brown- shirted hordes. Still, Hitler waited, for the balance that had been achieved seemed to hold the SA and the Reichswehr in check, each in its own way. Finally, it was the many enemies Rohm had accumulated in the course of his career who decided to pounce, beginning with such people as Rudolf Hess and Martin Bormann in party headquarters and extending all the way to the SA division heads. Most important was Hermann Goring, who felt driven into an alliance that he would have preferred to avoid. He joined forces with Heinrich Himmler, the chief of the SS, turning control of the Gestapo over to him. In aligning himself with Himmler he was also taking on Himmler’s assistant, Reinhard Heydrich, who had always struck him as eerie and sinister. By early May Heydrich had assumed responsibility for the operation against Rohm.

The change in the atmosphere was immediately palpable, as a veritable campaign was launched, complete