that there could be no question of a mass uprising or general strike like the one staged thirteen years earlier to thwart the Kapp putsch. There was also little hope for a coup from above by powerful elites in society and the government bureaucracy, so quickly and thoroughly had Hitler penetrated all social organizations.

One institution, however, had managed to preserve most of its traditional autonomy and internal cohesion: the army. As Hitler himself said at the time, half indignant and half impressed, it was “the last instrument of state whose worldview has survived intact.”29 The army alone also possessed the means to overthrow a regime so obsessed with security. Its great dilemma was that any coup it staged would put an enormous strain on long-standing loyalties and would necessarily threaten the continued existence of the state, to which it was deeply committed by tradition and professional ethic.

Nevertheless, whenever individuals or small groups came together to discuss conspiracy against the state, regardless of their background or concerns, their gaze turned almost inevitably to the military. Equally inevitably, for the reasons outlined above, all thought of resistance became part of a vicious circle, which determined the events of the next few years.

2. THE ARMY SUCCUMBS

In the early evening of February 3, 1933, only four days after bcoming chancellor, Hitler hurried to 14 Bendlerstrasse to pay a first formal call on the leaders of the Reichswehr. The military commanders were reputed to be remote, secretive, and arrogant, and Hitler had gone to the meeting with some trepidation, because he knew they would play a key role in both his immediate schemes to seize power in Germany and his more long-range plans for expansion abroad.

Hitler understood well that many of the younger officers sympathized with him and his movement, albeit in a rather vague way. They felt that the Weimar Republic had suffered in both its internal and foreign dealings from a lack of courage and resolve, and they looked now to Hitler to cast off the Treaty of Versailles, restore the prestige of the army, improve their chances for personal advancement and promotion, and bring about real social change. Hopes for a renewal so sweeping that it could be deemed a revolution were common, especially among the younger officers who later joined the resistance. Henning von Tresckow, for instance, campaigned for the Nazis in the officers’ mess in Potsdam as early as the late 1920s, dismissing detractors as hopelessly reactionary. Soon after the Nazis seized power Albrecht Mertz von Quirnheim had himself transferred to the SA. Helmuth Stieff and many others also threw in their lot with the new cause. There is apparently no truth, however, to the tale that an enthusiastic Stauffenberg placed himself at the head of a crowd surging through Bamberg in celebration of Hitler’s nomination as chancellor.1

Senior officers took quite a different view, though the Weimar Republic had always seemed alien to them as well. They had high hope’s that an authoritarian regime would not only wash away the “shame of Versailles” but also help reconcile the state and the army, thereby returning to them the influence they had once wielded in the corridors of government. Hitler’s talk of party and army as the “twin pillars” on which the National Socialist state rested seemed to imply that they would regain the political leverage they had lost under the republic. Senior officers also imagined themselves powerful enough to determine the bounds of their own authority, within which Hitler would be prevented from interfering. But even so, they had serious reservations about the Nazis’ rowdy, anarchistic behavior, their undisguised contempt for the law, the terrorism of the SA, and last but not least, the personage of the Fuhrer himself, whose vulgar, hucksterish ways prompted one senior officer to say what they all more or less felt: Hitler was “not a gentleman but just an ordinary guy.”2

In his official quarters on Bendlerstrasse, General Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, the army commander in chief, greeted Hitler with obvious skepticism. An officer who was present reported that Hammerstein introduced the chancellor “in a benevolently condescending fashion; the assembled phalanx of generals were coolly polite, and Hitler made modest, obsequious little bows in all directions. He remained ill at ease until after dinner, when he was allowed an opportunity to speak for a longer period at the table.”3 Drawing on all his skills of persuasion, Hitler did his best to win the officers over. He promised that conditions within Germany would be “completely reversed,” military preparedness would be improved, and-according to the notes of another of the participants-there would be “no tolerance of any views that run counter to the objectives [pacifism!]. Those who do not convert will have to be bent. Marxism will be eradicated, root and branch.” On the subject of foreign policy, Hitler referred primarily to abandoning the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and mentioned only in passing “the conquest of new Lebensraum in the East,” The latter comment did not arouse any particular surprise or doubts among the generals, who were skeptical about politicians to begin with and did not pay especially close attention to their exact words. More important to the assembled officers was Hitler’s assurance that, in contrast to developments in Italy, there would be “no amalgamation of the Reichswehr and the party-affiliated SA” and that the army would remain “apolitical and nonpartisan.”4 Many of the officers came away with the impression that Hitler would prove a more congenial chancellor than any of his predecessors over the previous few years, although opinion was divided. Applause was only polite, and Hitler himself remarked afterwards that he felt as if he was “talking to a wall the whole time.”5

The cracks that the Fuhrer nevertheless found in this wall were the newly appointed minister of defense, Werner von Blomberg, and the head of the Bureau of Ministers, Colonel Walter von Reichenau. Confounding the expectations of the German Nationalist leaders who helped make Hitler chancellor, these two military men would soon become enthusiastic supporters of the Nazi cause, though for very different reasons. Blomberg was an impulsive, unsettled figure, who in the course of his life had embraced in quick succession democracy, thee anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner, and Prussian socialism, then had come close to accepting Communism after a trip to Russia, and eventually had endorsed the authoritarian state, before falling for Hitler with all the exuberance of his nature. Later he said that in 1933 he was suddenly filled with feelings that he had never expected to experience again: faith, reverence for a leader, and total devotion to an idea. Hitler, he once remarked, acted on him “like a great physician.”6 According to Blomberg’s intimates, a friendly comment from the Fuhrer was enough to bring tears to his eyes.

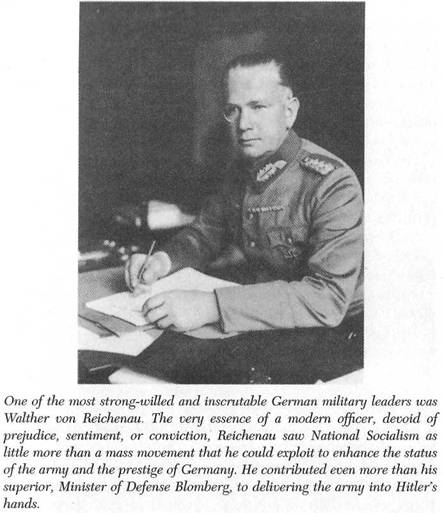

Reichenau, on the other hand, was the very embodiment of the modern officer, devoid of prejudice or sentiment. With the cool calculation of one lacking strong political sympathies of his own, he perceived the new men in government simply as the leaders of a mass movement whose strength he would tap to improve the position of the army and enhance Germany’s glory and prestige. A gifted man who combined elegance, toughness, and a taste for power, he was never personally tempted by National Socialism; he respected it as a political force without taking its ideology seriously. Reichenau believed that the Reichswehr, with its “seven antiquated divisions scattered across the entire country,” was totally incapable of asserting itself. To expect it to do so was a “daydream” suitable only to the realm of “fiction.” Hoping to cement the army’s relationship with Hitler, marginalize the Nazi Party, and edge out its paramilitary wing, the SA, he proposed that the Reichswehr adopt the motto “Forward into the new state.”7

Reichenau was relatively undisturbed by the excesses that accompanied the Nazi seizure of power. It always required an element of terror, he said soon alter assuming his new position, to purge a state of all its rot and decay. What did cause him considerable dismay, however, was the mounting power of the SA. Its ranks had swollen to over a million since the mass conversions of the spring of 1933, and it was expressing its dissatisfaction ever more vehemently. Hitler’s brown-shirted legions took a dim view of his legal revolution, which seemed to be undermining their interests, and they looked on bitterly as conservative politicians, aristocrats, capitalists, and generals-the very men whose worlds they wanted to smash-began assuming places of honor at celebrations of the national revival, while they, the eternally mistreated foot soldiers of the revolution, were expected simply to parade by.

The brownshirts felt they were the vanguard of the revolution, not just extras. They had learned from their slogans and songs how revolutions had been carried out since time immemorial: the fortresses of the old order were stormed in a torrent of bloodshed and plunder and the new order raised on the wreckage of the old-with the greatest rewards going to the most loyal soldiers. They could not understand Hitler’s sly concept of revolution by infiltration and ruse, and their rugged leader, Ernst Rohm, was particularly lacking in the patience and cunning required. And so, while the SA continued, in the disorderly style it had adopted in the spring of 1933, to sow