they so often have been-or dismissed as mere demagoguery.

Increasingly convinced of the hopelessness of any opposition and hard pressed by the persecution and prohibitions they faced, many opponents of the Nazis-especially those on the left-decided to leave Germany. In so doing, however, they were abandoning the workers to their fates, as Carlo Mierendorff, later one of the leaders of the resistance group known as the Kreisau Circle, pointed out at the time. “

Many people who felt torn by this dilemma have described what it meant for them. Wilhelm Hoegner, the future prime minister of Bavaria, recalled wandering through the streets of Munich feeling that all of a sudden they had become hostile and threatening.8 Helmuth von Moltke’s mother felt profoundly uprooted, as if she “no longer belonged to the country.”9 Others have spoken of losing old friends, of an atmosphere of suspicion, of spying neighbors and the rapid disintegration of their social lives even as the alleged brotherhood of all Germans was being celebrated in delirious parades and pseudo-religious services, mass swearings of oaths and vows under domes of light, addresses by the Fuhrer, nightly bonfires on hills and moun tains, secular chants and hymns. All this fervor was fueled by the intense sensation that history was in the making. For the first time since the rule of the kaisers, Germans seemed to be living in a country which celebrated both leadership and political liturgy.

In the week leading up to the March 5 Reichstag elections, the Nazis pushed both national exaltation and unbridled violence to new heights. Goebbels proclaimed March 5 the “Day of the Awakening Nation” and orchestrated nationwide mass demonstrations and parades, processions and carefully staged appearances. The brilliance and ubiquity of these events left the Nazis’ coalition partner, the German National People’s Party, completely overshadowed. Meanwhile, the other parties were subjected to every kind of sabotage and disruption, while the police sat idly by in accordance with their instructions. By election day fifty-one anti-Nazis lay dead and hundreds had been injured. The Nazis themselves counted eighteen dead. On the eve of the election Hitler appeared in the city of Konigsberg. Just as he was ending his rapt appeal to the German people—“Hold thy head high and proud once more! Now thou art free once again, with the help of God”—a hymn could be heard swelling in the background, and the bells of the Konigsberg cathedral pealed during the final stanza. Meanwhile, on the hills and mountains along Germany’s borders, “bonfires of freedom” were lit.

Nazi expectations of overwhelming victory at the polls and at least an absolute majority in the Reichstag were to be dashed, however. Despite all they had done to intimidate their opponents, the National Socialists increased their vote by only about six points, to 43.9 percent of the total. The other parties suffered only minor losses. Having failed to win an absolute majority, the Nazis were forced to continue relying on the German National People’s Party, together with whom they had a scant majority of 51.9 percent of the vote. Angered at the results, Hitler complained to his cronies on the evening of the election that he would never be free of that German National “gang” as long as Hindenburg was alive.10

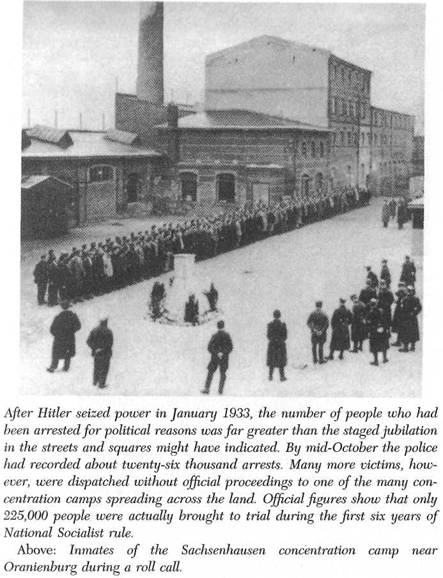

As the election results showed, many Germans were still unwilling to embrace the Nazis and their new era- far more unwilling, indeed, than Nazi propagandists would admit. Many citizens reacted to the election with curiously mixed feelings: enthusiasm for the new regime alternated with anxiety; hope for more jobs gave way to renewed doubts; confusion was resolved by the sense of pride the Nazis so skillfully evoked. Occasionally, especially on the far left, entire street-fighting organizations such as the Communist Rotfrontkampferbund switched sides, joining ranks with those who had been their bitter enemies only days before. On the right, many non-Nazi groups hastened to “get in line” or even disband before being forced to do so. All this is well documented, but far less is known of the countless opponents of the regime who simply “disappeared” during the first weeks and months of Nazi rule. Police records show that by mid-October 1933 about twenty-six thousand people had been arrested, while many more vanished without legal formalities into the hastily constructed concentration camps that were spreading across the land. According to official figures, some three million people were incarcerated for political transgressions during the twelve years of Nazi rule; another statistic, however, shows that only 225,000 people were actually brought to trial in political cases during the first six years.11

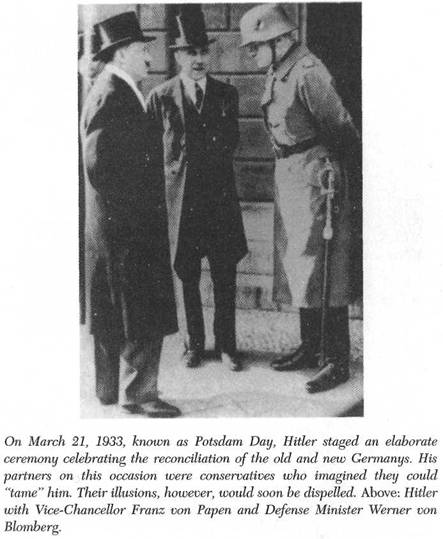

Our picture of these years would not be complete without mention of how all established political formations, on both the left and the right, melted away without resistance. Nothing so reveals the exhaustion of the Weimar Republic as the pathetic end of its political parties and organizations. Even Hitler was astonished: “Such a miserable collapse would never have been thought possible,” he said in Dortmund in early July 1933.12 Prohibitions, seizures of buildings, and confiscations of property that a short time before would have brought Germany to the verge of civil war now elicited only shrugs. A “Potsdam Day” ceremony on March 21, 1933, celebrated the inauguration of the new parliament with a review of troops, organ music, and gun salutes. Former chancellor Heinrich Bruning commented that when he joined a column of deputies headed for the garrison church, where the ceremony took place, he felt as if he were being taken “to the execution grounds.”13 There was more truth to this than he realized.

It could even be said that Bruning and his companions had sentenced themselves to their fate. They were not single-handedly responsible for the decline of the republic, even if they had hastened its demise through their weakness and blindness; the republic had had to face far too many opponents at home and abroad throughout its short life and was hardly blessed by good fortune. But the men who served it in high office were thoroughly lacking in judgment when they failed to recognize the extreme danger that Hitler posed to the German republic and to themselves and failed to take any measures of self-defense.

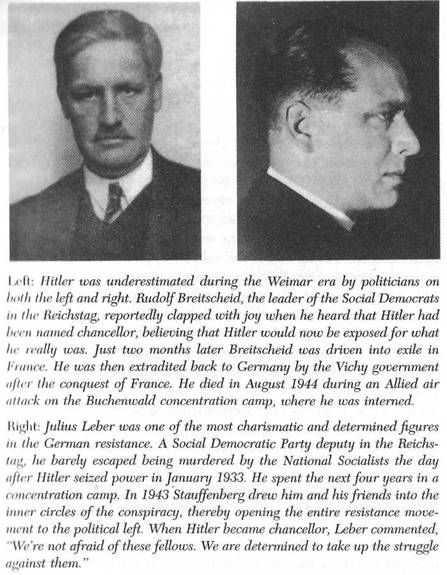

The Weimar leadership had been seeking to evade responsibility since 1930, with the SPD leading the way, attempting to recover its status as the “glorious opposition of old” while pointing ever more urgently to the mounting “threat to democracy.”14 In December 1932 Major General Kurt von Schleicher, who immediately preceded Hitler as chancellor, made a final stab at saving the republic, but that effort foundered, undermined by the cold indolence of the leaders who, while talking passionately of their commitment to democracy, abandoned the nation to its fate. Even after Hitler gained control of the “fortress,” as the republic was often called, they failed to recognize what was right before their eyes. When news arrived that Hitler had been named chancellor, Rudolf Breitscheid, the Social Democratic leader in the Reichstag, clapped with joy that Hitler would now show himself for what he really was. He did, of course, and Breitscheid met his end in Buchenwald. Julius Leber, who would become a leading figure in the resistance, commented disdainfully at the time that he, like everyone else, was looking forward finally to seeing “the intellectual foundations of this movement.”15

The miscalculations of those on the right, a result of arrogance and a lack of political instinct, were even more appalling. Their ideological affinities with the Nazis, their assumption of commonality on national issues, and their aversion to both democracy and Marxism led many to conclude that Hitler was just a radical version of themselves. The vast majority believed that conservative interests were safe in Hitler’s hands despite his distastefully rough, vulgar manner. In their condescending way, they assumed that they would soon be able to take this demagogue in hand and tame him. They confidently imagined they could restrict him to delivering speeches, staging Nazi circuses, and venting his “architectural spleen,” while they steered the ship of state. Although it should have been obvious to anyone who looked beneath the nationalistic, conservative surface, what the right failed to comprehend was the revolutionary essence of Nazism, bent on destroying the traditional bonds, loyalties, and outmoded social structures that the right-wing parties were so eager to restore. Hitler was no mere rabble-rouser whose popularity conservatives could exploit to solve their old problem of being a self-appointed ruling class without a following. It would be some time before they understood this. By 1938 Hjalmar Schacht, whom Hitler had reappointed to his old position as president of the Reichsbank, was overheard commenting to a table companion, “My dear lady, we have fallen into the hands of criminals. How could I ever have imagined it!”16