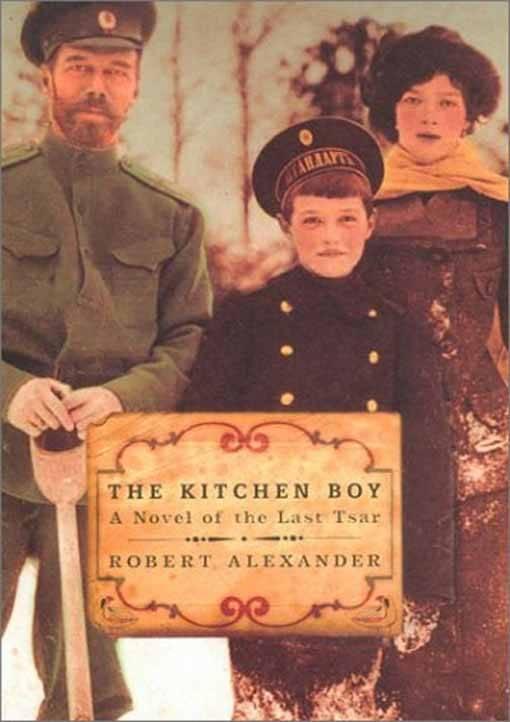

Robert Alexander

The Kitchen Boy

© 2003

In memory of my mother,

Elizabeth Cottrell

PROLOGUE

Saint Petersburg, Russia

Summer 2001

Peering through the peephole of her apartment door, the old woman didn’t know what to do. Finally, she cleared her throat and called out in a voice as frail as an October leaf.

On the other side of the thick, padded door, the young stranger, tall and striking, her hair brown and thick, replied not in Russian, but English, saying, “A friend from America.”

Instantly, the babushka’s weary eyes blossomed with tears. It could be no one else. It had to be the girl from Chicago. And realizing it was the moment she had both feared and prayed for, the aged Russian beat her chest in a frantic cross. Next, almost without thinking, her hands worked the crude Soviet lock and she heaved back the door. Fully aware of their miraculous collision of fate, the two women stood in quiet awe.

The American, her eyes shimmering with tears of relief and grief, broke the awkward silence. “Perhaps you don’t realize who I am, but-”

In a language she had barely spoken since before the times of Stalin, the woman strained for the English words, and in a hushed, careful voice said, “I know who you are, dear Katya. Of course I do, and not just from what they write of you in these newspaper stories, either.

Hiding her pain behind a pathetic smile, the young woman pulled a cassette tape from her black leather purse. “My grandfather left this for me.”

“I see,” muttered the babushka with a wise cluck of her tongue. “Now come in, my child. Come in quickly. We have much to discuss and you can’t be seen standing out here.”

1

America

Summer 1998

“My name is Mikhail Semyonov. I live in Lake Forest village, Illinois state, the United States of America. I am ninety-four years old. I was born in Russia before the revolution. I was born in Tula province and my name then was not Mikhail or even Misha, as I am known here in America. No, my real name – the one given to me at birth – was Leonid Sednyov, and I was known as Leonka. Please forgive my years of lies, but now I tell you the truth. What I wish to confess is that I was the kitchen boy in the Ipatiev House where the Tsar and Tsaritsa, Nikolai and Aleksandra, were imprisoned. This was in Siberia. And… and the night they were executed I was sent away. They sent me away, but I snuck back, and that night, the moonless night of July 16-17, 1918, I saw the Tsar and his family come down the back twenty-three steps of the Ipatiev House, I saw them go into that cellar room… and I saw them shot. Trust me, believe me, when I say this: I am the last living witness and I alone know what really happened that awful night… just as I alone know where the bodies of the two missing children are to be found. You see, I took care of them with my own hands.”

Misha took a deep breath, tried to push himself on, but couldn’t. Panicking, he hit the

Over the many years since the Russian Revolution, Misha had come to realize that on a single night in 1918 he had witnessed far too much for an entire lifetime, particularly in the tortured silence he had so sternly observed in the ensuing decades. But such was his punishment. He was an old man, certain that this long life and clear memory were the torture he deserved. Yes, there was a God, for if there were not he would have been spared this suffering. Instead he kept on living. And remembering. True, he had gained some wisdom, for over the course of all this time he had come to look at that night as the start of everything horrible that had since befallen his poor Rossiya. As he looked back from these United States and through the distance of the decades, it was all so clear. A great curse was unleashed that night, inundating every corner of his vast homeland. If his comrades could commit such an act, was it any wonder that Stalin could kill upward of twenty million of his own people? No, of course not. On a hot night in the Siberian city of Yekaterinburg the individual had become expendable.

Misha was a tall man who walked with the slightest of limps, but over the last fifteen years, of course, he had grown smaller and his gait more halting as his body had settled and lost muscle mass. He’d always been trim, and it was this leanness that had undoubtedly contributed to his longevity and his lack of major illness. His hair, which he had always combed straight back in an elegant manner, had been snow white for more than thirty years, and while it had receded only slightly, it had definitely thinned. His face was narrow and long, his nose simply narrow, while his upper lip was straight and noticeably, almost oddly, small. Since his fifties, the tone of his skin had gone from robust to ruddy to its present parchment color, skin that now hung loosely from his sharp cheekbones. Always a dapper dresser, he wore lightweight gray wool pants and a yellow cashmere sweater over a pressed and starched blue shirt from Brooks Brothers.

Seated in a wrought iron chair on the raised terrace behind his grand, twenty-room house, he stared out over the bluff and at the lake, himself the very image of old Chicago money. Nothing, however, could have been further from the truth, for when he’d arrived in the United States in 1920 he’d had but a rucksack, one suitcase, and the clothes he was wearing. And while everyone believed that he’d made his millions on the stock market down at the Chicago Board of Trade, that too was a lie, albeit one that he had carefully cultivated.

Staring out at Lake Michigan, Misha was transfixed by the flashes of light upon the blue water, flashes that sparkled like diamonds. He’d been tormented his entire life because of that night more than eighty years ago, a night which until now he’d never spoken of to anyone except May, his beloved wife. But now he must, now he had no choice. May was already two weeks in the grave, and he was determined to follow her as soon as possible. Before he left this world, however, he had certain obligations, namely, to reveal a kind of truth to their only heir, their lovely granddaughter, Kate. May, who’d also fled Russia after the revolution, fully understood the delicacy of the matter, and even though she’d helped Misha decide just how it might be done, he’d put it off. Now, however, the time had come, he could wait no more: he must give the young woman not simply a way to understand, but a