the hand. Levinson assumed that the movement indicated that when one entered the shop the frozen fish were to be found on the right-hand side. But no, it turned out that the fish were actually on the left when you entered the shop. So why the gesture to the right? Roger was not gesturing to the right at all. He was pointing to the northeast, and expected his hearer to understand that when he went into the shop he should look for the fish in the northeast corner.

It gets curiouser. When older speakers of Guugu Yimithirr were shown a short silent film on a television screen and then asked to describe the movements of the protagonists, their responses depended on the orientation of the television when they were watching. If the television was facing north and a man on the screen appeared to be approaching, the older men would say that the man was “coming northward.” One younger man then remarked that you always know which way the TV was facing when the old people tell the story.

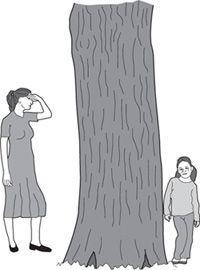

The same reliance on geographic directions is maintained even when speakers of Guugu Yimithirr are asked to describe a picture inside a book. Suppose the book is facing top side north. If a man is shown standing to the left of a woman, speakers of Guugu Yimithirr would say, “the man is to the west of the woman.” But if you rotate the book top side east, they will say, about exactly the same picture, “the man is to the north of the woman.” Here, for instance, is how one Guugu Yimithirr speaker described the above picture (guess which way he was facing):

If you are reading a book facing north, and a Guugu Yimithirr speaker wants to tell you to skip ahead, he will say, “go further east,” because the pages are flipped from east to west. If you are looking at it facing south, the Guugu Yimithirr will of course say, “go further west.” They even dream in cardinal directions. One person explained how he entered heaven in a dream, going northward, while the Lord was coming toward him southward.

There are words for “left hand” and “right hand” in Guugu Yimithirr. But they are used only to refer to the inherent properties of each hand (for instance, to say “I can lift this with my right hand but not with my left hand”). Whenever the

In our language, the coordinates rotate with us whenever and wherever we turn. For the Guugu Yimithirr, the axes always remain constant. One way of visualizing this difference is to think of the two options on the displays of satellite navigation systems. Many of these gadgets let you choose between a “north up” and a “driving direction up” display. In the “driving direction up” mode, you always see yourself moving directly upwards on the screen, but the streets around you keep rotating as you turn. In the “north up” mode, the streets always stay in the same position, but you see the arrow representing you turning in different directions, so that if you are driving south, the arrow will be moving downwards. Our linguistic world is primarily in the “driving direction up” mode, but in Guugu Yimithirr one speaks exclusively in the “north up” mode.

The first reaction to these reports would be to dismiss them as an elaborate practical joke played by bored Aborigines on a few gullible linguists, not unlike the tall stories of sexual liberation that were told to the anthropologist Margaret Mead by adolescent Samoan girls in the 1920s. The Guugu Yimithirr may not have heard of Kant, but they somehow must have got their hands on

Well, it turns out that Guugu Yimithirr is not quite as unusual as one might imagine. Once again, we have simply mistaken the familiar for the natural: the egocentric system could be paraded as a universal feature of human language only because no one had bothered to examine in depth those languages that happen to do things differently. In retrospect, it seems strange that such a striking feature of many languages could have gone unnoticed for such a long time, especially since clues had been littering the academic literature for a while. References to unusual ways of talking about space (such as “your west foot” or “could you pass me the tobacco there to the east”) appeared in reports about various languages around the world, but it was not clear from them that such unusual expressions went beyond the occasional oddity. It took the extreme case of Guugu Yimithirr to inspire a systematic examination of the spatial coordinates in a large range of languages, and only then did the radical divergence of some languages from what had previously been considered universal and natural start sinking in.

To begin with, in Australia itself the reliance on geographic coordinates is very common. From the Djaru language of Kimberley in Western Australia, to Warlbiri, spoken around Alice Springs, to Kayardild, once spoken on Bentinck Island in Queensland, it seems that most Aborigines speak (or at least used to speak) in a distinctly Guugu Yimithirr style. Nor is this peculiar way merely an antipodean aberration: languages that rely primarily on geographic coordinates turn out to be scattered around the world, from Polynesia to Mexico, from Bali and Nepal to Namibia and Madagascar.

Other than Guugu Yimithirr, the “geographic language” that has received the most attention so far is found on the other side of the globe, in the highlands of southeastern Mexico. In fact, we have already come across the Mayan language Tzeltal, in an entirely different context. (Tzeltal was one of the languages in Berlin and Kay’s 1969 study of color terms. The fact that its speakers chose either a clear green or a clear blue as the best example of their “grue” color was an inspiration for Berlin and Kay’s theory of universal foci.) Tzeltal speakers live on a side of a mountain range that rises roughly toward the south and slopes down toward the north. Unlike in Guugu Yimithirr, their geographic axes are based not on the compass directions North-South and East-West but rather on this prominent feature of their local landscape. The directions in Tzeltal are “downhill,” “uphill,” and “across,” which can mean either way on the axis perpendicular to uphill-downhill. When a specific direction on the across axis is required, Tzeltal speakers combine “across” with a place-name and say “across in the direction of X.”

Geographic coordinate systems that are based on prominent landmarks are also found in other parts of the world. In the language of the Marquesas Islands of French Polynesia, for example, the main axis is defined by the opposition sea-inland. A Marquesan would thus say that a plate on the table is “inland of the glass” or that you have a crumb “on your seaward cheek.” There are also systems that combine both cardinal directions and geographic landmarks. In the language of the Indonesian island of Bali, one axis is based on the sun (East-West) and the other axis is based on geographic landmarks: it stretches “seaward” on one side and “mountainward” on the other, toward the holy volcano Gunung Agung, the dwelling place of the Hindu gods of Bali.

Earlier on I said that it would be the height of absurdity for a dance teacher to say things like “now raise your north hand and take three steps eastwards.” But the joke would be lost on some. The Canadian musicologist Colin McPhee spent several years on Bali in the 1930s, researching the musical traditions of the island. In his book

Why didn’t the teacher try to use different instructions? He would probably have replied that saying “take three