west! He maintained the correct geographic direction of the boat’s movement, without even giving it a moment’s thought. And as it happens, at the time of year when the accident happened there are strong southeasterly winds in the area, so flipping from east to west seems very likely.

Levinson also relates how a group of Hopevale men once had to drive to Cairns, the nearest city, some 150 miles to the south, to discuss land-rights issues with other aboriginal groups. The meeting was in a room without windows, in a building reached either by a back alley or through a car park, so that the relation between the building and the city layout was somewhat obscured. About a month later, back in Hopevale, he asked a few of the participants about the orientation of the meeting room and the positions of the speakers at the meeting. He got accurate responses, and complete agreement, about the orientation in cardinal directions of the main speaker, the blackboard, and other objects in the room.

What we have established so far is that speakers of Guugu Yimithirr have to be able to recall anything they have ever seen with the crisscross of the cardinal directions as part of the picture. It is almost a tautology to say, therefore, that they must commit to memory a whole extra layer of spatial information that we are blithely unaware of. After all, people who say “the fish in the northeast corner of the shop” obviously have to remember that the fish was in the northeast corner of the shop. Since most of us do not remember whether fish are in northeast corners of shops (even if we could work it out at the time), this means that Guugu Yimithirr speakers register and remember information about space that we do not.

A more controversial question is whether this difference means that Guugu Yimithirr and English ever lead their speakers to remember different versions of the same reality. For example, could the crisscross of cardinal directions that Guugu Yimithirr imposes on the world make its speakers visualize and recall an arrangement of objects in space differently from us?

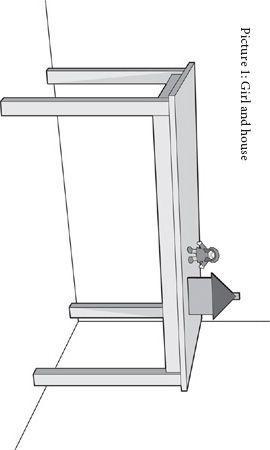

Before we can see how researchers tried to test such questions, let’s first play a little memory game. I’m going to show you some pictures with a few toy objects arranged on a table. There are three objects in all, but you will see at most two at a time. What you have to do is try to remember their positions, in order to complete the picture later on. We start with picture 1, where you can see a house and a girl. Once you have memorized their positions, turn to the next page.

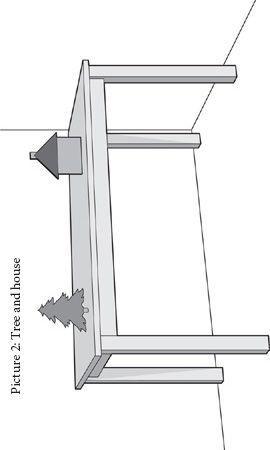

Now, in picture 2, you can see the house from the previous picture, and a new object, a tree. Try to remember the position of these two as well, and then turn to the next page.

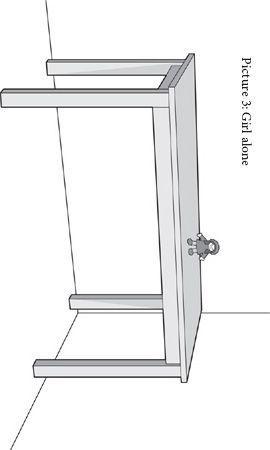

Finally, in picture 3, you see just the girl on the table. Now imagine I gave you the toy tree and asked you to place this tree in a way that would complete the picture and would be consistent with the two layouts you saw before. Where would you put it? Make a small mark (mental or otherwise) on the table before you turn to the next page.

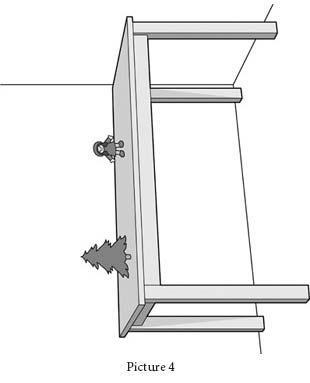

This is not a terribly difficult game, and it doesn’t take prophetic powers to predict where you placed the tree. Your arrangement must have been more or less what is shown in picture 4, as you would have followed the obvious clues: earlier, the girl was standing immediately to the left of the house, whereas the tree was much farther to the left. So this must mean that the tree was farther to the left than the girl. If there is any difficulty here, it is only to understand what the point is in doing such obvious exercises.

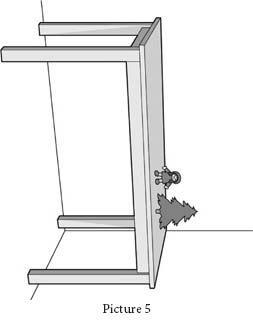

The point is that for speakers of Guugu Yimithirr or Tzeltal, the solution you have suggested does not seem obvious at all. In fact, when they were given tasks of this nature, they completed the picture in a very different way. They did not put the tree anywhere to the left of the girl, but rather on her other side, to the right, as in picture 5.

But why should they get such a simple task so badly wrong? There was nothing wrong about their solution, thank you very much. But there was something wrong about the way I just described it, because contrary to what I said, they did not put the tree “to the right of the girl.” They put it to the south of her. In fact, their solution makes perfect sense if one is thinking in geographic and not egocentric coordinates. To see why, let’s assume that you are reading this book facing north. (You can always turn to face the north, if you know where it is, just to avoid confusion.) If you look back at picture 1, you’ll see that the house was to the south of the girl. In picture 2, the tree was to the south of the house. Clearly, then, the tree must be south of the girl, since it is farther south from the house, which is farther south from the girl. So when completing the picture, it’s perfectly sensible to put the tree to the south of the girl, as in picture 5.

The reason the two solutions diverge is that in this game the table in picture 2 was rotated 180 degrees from the other pictures. We, who think in egocentric coordinates, automatically factor out this rotation and ignore it, so it has no bearing on the way we remember the arrangement of the objects on the table. But those who think in geographic coordinates do not ignore the rotation, and so their memory of the same arrangement is different.

In the actual experiments conducted by Levinson and his colleagues from the Max Planck Institute in Nijmegen, the two tables were not on adjacent pages of a book but in adjacent rooms (as in the picture on the facing page). The participants were shown an arrangement on a table in one room, then moved to a facing room and shown the second arrangement on a second table, and then finally brought back to the first room to solve the puzzle and complete the picture on the first table. The rotation pattern was just as in the preceding pictures, only in real life and on real tables. Many varieties of such experiments have been conducted with speakers of different languages. And the results of these experiments show that the preferred coordinate system in the language correlates strongly with the solutions the participants tend to pick. Speakers of egocentric languages like English overwhelmingly chose the egocentric solution, whereas speakers of geographic languages like Guugu Yimithirr and Tzeltal chose the geographic solution.

On one level, the results of these experiments speak for themselves, but there has been some controversy in the last few years about how to interpret their significance. Whereas Levinson has claimed that the results demonstrate deep cognitive differences between speakers of languages with egocentric and geographic coordinates, some of his claims have been contested by other researchers. As usual in academic controversies, much of the debate boils down to bickering over ill-defined terms: is the effect of language strong enough to “restructure cognition” (whatever that might mean exactly)? But on the factual level, the main argument leveled against the experiments was that the choice of solution can easily be biased by the physical environment in which they are conducted.

For example, participants might be encouraged to choose an egocentric solution if the two rooms are arranged so that they look the same from the egocentric perspective-say with the table on the right in both rooms and a cupboard to the left of the table in both rooms. On the other hand, a geographic solution might be encouraged if the environment is arranged to favor the geographic perspective-for instance, if the experiment is conducted in the open air, in view of a prominent geographic landmark. But while the point is well taken in general, in this particular experiment it serves only to strengthen the “strangeness” of the solution chosen by speakers of Guugu Yimithirr-style languages, because the two rooms in Levinson’s experiment were arranged to look exactly the same from the egocentric perspective. The table was on the right in both rooms (which meant it was in the north in one room and in the south in another), and all other furniture was arranged accordingly. And