Noel Hynd

Countdown in Cairo

The third book in the Russian Trilogy series, 2010

For Andy Meisenheimer and Bob Hudson at Zondervan.

Thanks, guys. Let’s do three more.

Whoever does not miss the Soviet Union has no heart. Whoever wants it back has no brain.

Vladimir Putin

Beware: Some liars tell the truth!

Ancient Arab proverb

Part One

ONE

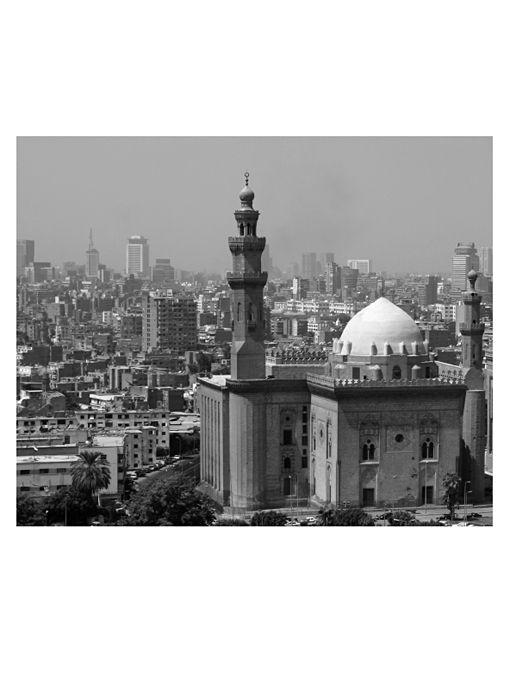

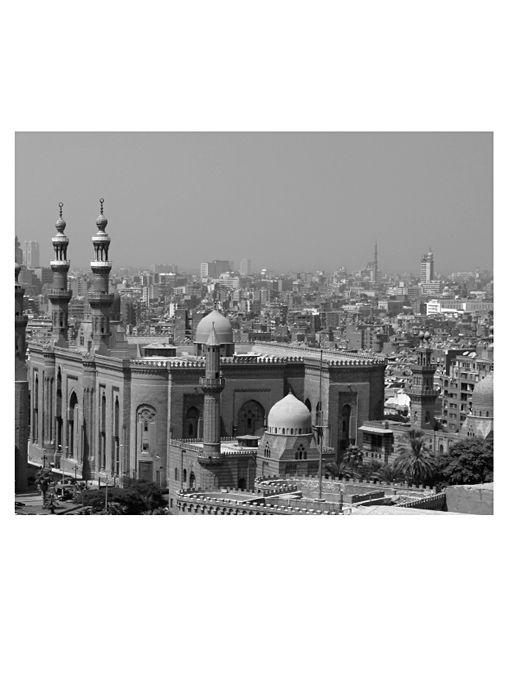

On a scorching afternoon, a few kilometers south of Cairo, a black bullet-resistant Land Rover pulled to an abrupt halt in front of the wide glass doors that marked the entrance to the Islamic morgue in the “ new city ” of Bahjat al-Jaafari. The morgue was a loathsome place, filled with the messy ugly detritus of death: foul stench and raw misery, oppressive heat and the sounds of unvarnished mourning; the cries of relatives and friends echoing down the narrow fetid corridors. It was in a separate wing of the pale redbrick medical center where the local police and doctors kept their records. So many dead bodies arrived here daily that piles of human remains were stacked on top of each other, separated by canvas wrappings or stained linen sheets. The morgue was located next to the hospital emergency room. The distinction was vague.

The vehicle was a relatively recent model, though not without its share of dents, and had a license plate that said it was on official business. It began and ended with robust, combative bumpers and spiked hubs that looked like weapons from a Bond film. Its windows were made of thick tinted glass, three radio antennas pierced the air, and there were enough red and blue lights on the dashboard to mark the runway of an airport.

Three men jumped out, almost before the vehicle had stopped rolling. One was Gian Antonio Rizzo, an Italian in a suit, reflective sunglasses, and a grim face. He carried his jacket over his arm, revealing an automatic pistol on his belt. Rizzo was on a black assignment from the Americans, though he would never admit that he worked for them. He still carried the documents of the Italian intelligence service, the Servizio per le Informazioni e la Sicurezza Militare, and actually did drop by their offices a few times a year.

The second man was a metropolitan Cairo policeman named Colonel Amjad, a pudgy but muscular man with a moustache and dark glasses. The third was an adjunct officer named Ghalid Nasri from the US Embassy in Cairo. Ghalid was acting as an intermediary-a diplomatic liaison and an interpreter for the haggard Rizzo-and was trying not to get shot while doing it. Both men carried pistols under their outer garments, as did their driver. They were all in that line of work.

The “new city” of Bahjat al-Jaafari had been built after the Six Day War of 1973, so it was now old enough to have fallen into decay. Gangs and death squads roamed its streets and the endless dunes of the desert beyond, areas that were supposed to be under the control of the central government in Cairo but were not. The area was in anarchy, and the anarchy went unnoticed until it touched upon Western visitors, who were frequent victims if they wandered off the tourist paths. Even then, however, as long as the bulk of the tourists kept coming, the dead did not count. An old Egyptian proverb has it that the dead have no voice, and this was never truer than here.

Rizzo bullied his way through the front doors of the medical complex, bumping shoulders with anyone who didn’t give way. The other two men accelerated their pace to stay with him. Then they entered the dilapidated lobby that was only marginally cooler than the broiling outdoors. Rizzo spotted a front desk that served as a registry and information booth. A middle-aged man in traditional Arab clothing looked up and greeted him politely.

“Ahlan bik,” Rizzo answered sharply. He was having none of the politeness.

“La ilaha illa Allah,” said the man.

“I’m here to see a Dr. Badawi,” Rizzo said, “your medical examiner.”

“For what purpose?” the man asked.

Rizzo looked as if he were about to explode. What did it matter to this fool

Amjad, the Cairo policeman, interposed himself. “We’re here to view a body,” he said in Arabic.

“View or identify?” the man asked.

Rizzo seethed. “Is there a bloody difference?”

“Both,” Amjad said, trying to sooth Rizzo. “And with extreme urgency.”

The Cairo detective flashed an array of police identifications. At first the Cairo police IDs flustered the man at the desk, but quickly they accelerated everything. The clerk wrote out a pass-Room 107-and indicated the direction. Rizzo snatched the pass from the clerk’s hand.

“There is no God but Allah, and Mohammed is his messenger,” the clerk said in Arabic. The Cairo cop gave him a nod. Rizzo snarled something profane and took off. He forged across the lobby and down a shabby overheated corridor, where two bodies were stacked up on a single gurney. It was so hot that there was condensation on the walls.

They passed a door. Rizzo glanced in. Two young doctors, both of them Western women, conversed in English with what Rizzo recognized to be British accents. They were frantically trying to resuscitate premature babies while other infants wailed in the background. There had been one of the frequent power cuts in this area earlier in the day, Rizzo knew. The Egyptian health care system was a national calamity, a system suffering from underfinancing, overpopulation, and a long history of mismanagement and corruption.

Rizzo strode toward Room 107. He had been in morgues in the Middle East before and they were all awful, much worse than the ones in Europe. Many times in the past Rizzo had been called to identify remains that had been ripped apart by gunfire or explosions, sometimes by suicide bombers. Other times he had come to identify victims who had been deliberately disfigured by their killers. He had never ceased to be appalled at the sadism inflicted on the dead. He had seen many who had obviously been tortured, mostly men, often with terrible burn marks on their faces, hands, feet, or other parts of their bodies.

Then there had been the executions, both political and gangland. Some of these victims had had their hands fastened behind their backs with handcuffs and their eyes had been bound with tape. They had been shot in the back of the head or in the face or in the temple. The cruelty in this part of the world, fanned by centuries of religious hatred, could be unspeakable.

Through his career in police work, crime reports-words on paper-had led him to understand intellectually what had happened. But visits to morgues were the images that haunted him, that sometimes caused him to bolt upright at night from sleep, howling.

Rizzo led Amjad and Ghalid into the room marked 107.

The room was plain and sterile, light green paint peeling off the walls. There were a few chairs, an empty space in the middle of the chamber, and a dented steel door that led somewhere else. Rizzo turned to Ghalid, his aide from the American embassy.

“Now what?” Rizzo snarled.

“We wait for the body,” Ghalid said, indicating the steel door.

“For how long?”

“Until it arrives,” said Ghalid.

“In this part of the world, Signor Rizzo,” Colonel Amjad began, “we must observe-”

“Go to hell!” Rizzo snapped. His eyes found Amjad’s gaze trying to penetrate his. He returned the gaze with a glare filled with dislike, bordering on hatred. “Your country is the hellhole I remember it to be. It suits you perfectly.”