While this experiment did not measure the actual color sensation directly, it did manage to measure objectively the second-best thing, a reaction time that is closely correlated with visual perception. Most importantly, there was no reliance here on eliciting subjective judgments for an ambiguous task, because participants were never asked to gauge the distances between colors or to say which shades appeared more similar. Instead, they were requested to solve a simple visual task that had just one correct solution. What the experiment measured, their reaction time, is something that the participants were neither conscious of nor had control over. They just pressed the button as quickly as they could whenever a new picture appeared on the screen. But the average speed with which Russians managed to do so was shorter if the colors had different names. The results thus prove that there is something objectively different between Russian and English speakers in the way their visual processing systems react to blue shades.

And while this is as much as we can say with absolute certainty, it is plausible to go one step further and make the following inference: since people tend to react more quickly to color recognition tasks the farther apart the two colors appear to them, and since Russians react more quickly to shades across the

Of course, even if differences between the behavior of Russian and English speakers have been demonstrated objectively, it is always dangerous to jump automatically from correlation to causation. How can we be sure that the Russian language in particular-rather than anything else in the Russians’ background and upbringing-had any causal role in producing their response to colors near the border? Maybe the real cause of their quicker reaction time lies in the habit of Russians to spend hours on end gazing intently at the vast expanses of Russian sky? Or in years of close study of blue vodka?

To test whether language circuits in the brain had any direct involvement with the processing of color signals, the researchers added another element to the experiment. They applied a standard procedure called an “interference task” to make it more difficult for the linguistic circuits to perform their normal function. The participants were asked to memorize random strings of digits and then keep repeating these aloud

When the experiment was repeated under such conditions of verbal interference, the Russians no longer reacted more quickly to shades across the

An even more remarkable experiment to test how language meddles with the processing of visual color signals was devised by four researchers from Berkeley and Chicago-Aubrey Gilbert, Terry Regier, Paul Kay (same one), and Richard Ivry. The strangest thing about the setup of their experiment, which was published in 2006, was the unexpected number of languages it compared. Whereas the Russian blues experiment involved speakers of exactly two languages, and compared their responses to an area of the spectrum where the color categories of the two languages diverged, the Berkeley and Chicago experiment was different, because it compared… only English.

At first sight, an experiment involving speakers of only one language may seem a rather left-handed approach to testing whether the mother tongue makes a difference to speakers’ color perception. Difference from what? But in actual fact, this ingenious experiment was rather dexterous, or, to be more precise, it was just as adroit as it was a-gauche. For what the researchers set out to compare was nothing less than the left and right halves of the brain.

Their idea was simple, but like most other clever ideas, it appears simple only once someone has thought of it. They relied on two facts about the brain that have been known for a very long time. The first fact concerns the seat of language in the brain: for a century and a half now scientists have recognized that linguistic areas in the brain are not evenly divided between the two hemispheres. In 1861, the French surgeon Pierre Paul Broca exhibited before the Paris Society of Anthropology the brain of a man who had died on his ward the day before, after suffering from a debilitating brain disease. The man had lost his ability to speak years earlier but had maintained many other aspects of his intelligence. Broca’s autopsy showed that one particular area of the man’s brain had been completely destroyed: brain tissue in the frontal lobe of the left hemisphere had rotted away, leaving only a large cavity full of watery liquid. Broca concluded that this particular area of the left hemisphere must be the part of the brain responsible for articulate speech. In the following years, he and his colleagues conducted many more autopsies on people who had lost their ability to speak, and the same area of their brains turned out to be damaged. This proved beyond doubt that the particular section of the left hemisphere, which later came to be called “Broca’s area,” was the main seat of language in the brain.

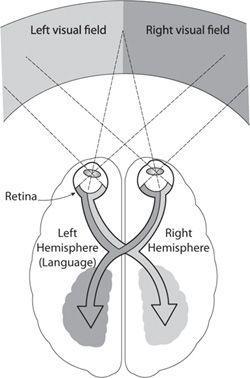

Processing of the left and right visual fields in the brain

The second well-known fact that the experiment relied on is that each hemisphere of the brain is responsible for processing visual signals from the opposite half of the field of vision. As shown in the illustration above, there is an X-shaped crossing over between the two halves of the visual field and the two brain hemispheres: signals from our left side are sent to the right hemisphere to be processed, whereas signals from the right visual field are processed in the left hemisphere.

If we put the two facts together-the seat of language in the left hemisphere and the crossover in the processing of visual information-it follows that visual signals from our right side are processed in the same half of the brain as language, whereas what we see on the left is processed in the hemisphere without a significant linguistic component.

The researchers used this asymmetry to check a hypothesis that seems incredible at first (and even second) sight: could the linguistic meddling affect the visual processing of color in the left hemisphere more strongly than in the right? Could it be that people perceive colors differently, depending on which side they see them on? Would English speakers, for instance, be more sensitive to shades near the green-blue border when they see these on their right-hand side rather than on the left?

To test this fanciful proposition, the researchers devised a simple odd-one-out task. The participants had to look at a computer screen and to focus on a little cross right in the middle, which ensured that whatever appeared on the left half of the screen was in their left visual field and vice versa. The participants were then shown a circle made out of little squares, as in the picture above (and in color in figure 9).